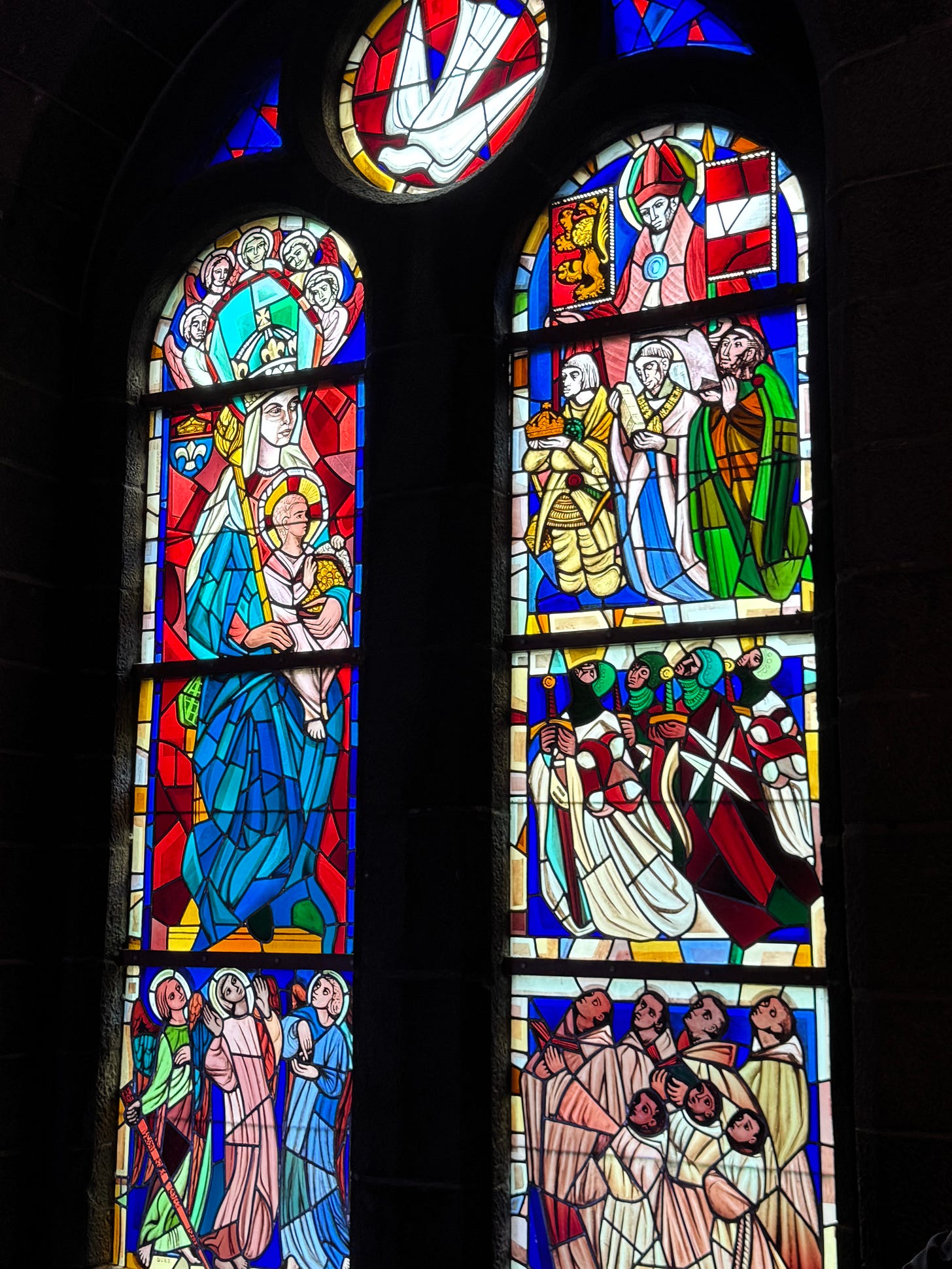

Stained Glass, Benedictine Abbey of Keizersberg (Mont César), Leuven (Louvain). On the right, the Emperor Charles V offers his crown to the Virgin and Child.

What follows is a talk I delivered at an excellent symposium on “Mary and Political Philosophy”, organized by Sedes Sapientiae in Leuven (Louvain) in 2024. One of the organizers was Dr. Michaël Bauwens, who recently published a Marian account of political theology in our pages.

I have left the talk substantially as delivered, with a minimum of academic apparatus and some irrelevant material deleted. Part of the charge given to me by the organizers was to do a concluding reflection on the other papers; hence the readers will notice a few oblique references to talks given by others, but I hope the point of my references is self-explanatory in context.

— Adrian Vermeule

Thank you for having me. My paper has a title: “The Fiat of the Prince: On the Marian Foundations of the Rule of Law.” You will immediately observe that “fiat” is said in several ways here. First and foremost, it refers to Mary’s obedience to the divine will, the Fiat of Mary (ecce ancilla Domini fiat mihi secundum verbum tuum, “behold the handmaiden of the Lord; let it be done to me according to thy word”). Second, and very differently, a fiat is a sovereign decree, the legal command of a superior to an inferior. Third, and this is my thesis, there is a paradoxical connection between the first two senses: the rule of law is founded on the Marian fiat of the prince, whose office of command is justified when and because he submits to the natural and divine law, just as the Blessed Virgin submitted to the divine Word.

I have to begin in a very modern fashion: this is the first and possibly last time I have been invited to a conference because of a tweet. It was one that I made on the memorial of the Queenship of Mary in 2023, mentioning the possibility of a Marian foundation for the rule of law. I will expand upon the tweet with just a few more characters than twitter allows.

Let me begin with that rather large question: What is the foundation of the rule of law? The modern answers are familiar. Among them are equal justice, treating like cases alike; the prevention of arbitrary exercise of power; the protection of human dignity; and legal certainty and predictability. These are right as far as they go, or at least not exactly wrong, but I will explore an older answer, given by (or at least in the name of) the English civilian jurist Bracton — an answer that I think places the rule of law in a wider and deeper perspective. On the view I will explore, the foundation of the rule of law is Marian political theology, specifically a Marian interpretation of the Digna Vox, a famous text of the Roman civil law.

“Bracton,” or more precisely the text conventionally attributed to Henry of Bracton (1210-68), is probably a collective work of the mid-13th century, on the laws and customs of England. The Bracton text brought a distinctively Romanizing influence to English law, with the extent and duration of that influence being a much-debated topic. Bracton writes: “The king has no equal within his realm. Subjects cannot be the equals of the ruler, because he would thereby lose his rule, since equal can have no authority over equal, nor a fortiori a superior, because he would then be subject to those subjected to him. The king must not be under man but under God and under the law, because law makes the king…. Jesus Christ willed himself to be under the law that he might redeem those who live under it. For He did not wish to use force but judgment. And in that same way the Blessed Mother of God, the Virgin Mary, Mother of our Lord, who by an extraordinary privilege was above law, nevertheless, in order to show an example of humility, did not refuse to be subjected to established laws. Let the king, therefore, do the same, lest his power remain unbridled” (emphasis added).

I want to bring this passage into association with the Digna Vox, which Bracton’s text unmistakably echoes. The latter is a fundamental constitution or imperial edict of the Codex Theodosianus (later embodied in the Codex Justinianus), and was issued jointly at Ravenna in 429 by the Christian co-emperors Theodosius II in the west and his son-in-law Valentinian III in the east. It is a principal, founding text of the rule of law in the Western legal tradition — and, I note tendentiously against more recent legal theorists, long predates any talk of subjective rights in the modern sense, or the separation of powers, or judicial review, or any of a number of other legal mechanisms that are now sometimes said to be essential to the rule of law. I suppose the Digna Vox is quite familiar to civil lawyers and probably to a number of non-lawyers too, but I take the liberty of quoting it just because of the majesty of the proclamation, which itself explains in what consists the majesty and authority of the prince.

Cod. 1.14(17).4

Imperatores Theodosius, Valentinianus

Digna vox maiestate regnantis legibus alligatum se principem profiteri: adeo de auctoritate iuris nostra pendet auctoritas. Et re vera maius imperio est submittere legibus principatum. et oraculo praesentis edicti quod nobis licere non patimur indicamus. * theodos. et valentin. aa. ad volusianum pp. * <a 429 d. iii. id. iun. ravennae florentio et dionysio conss.>

Emperors Theodosius and Valentinian

It is a statement worthy of the majesty of a reigning prince for him to profess to be subject to the laws; for our authority is dependent upon that of the law. And, indeed, it is the greatest attribute of imperial power for the sovereign to be subject to the laws. By this present edict we forbid others to do what we do not permit ourselves. Given at Ravenna, on the third of the Ides of June, during the Consulate of Florentinus and Dionysius, 429.

For our purposes, the key question is: why does Bracton seem to translate the Digna Vox into not merely a Christological but also, and distinctively, a Marian register? I do not mean to say Bracton was the first to associate Mary with humility and obedience to law. The idea has its own long history in political and legal theology. Bracton for example echoes a similar formulation by Bede, who writes that “[the Lord’s] blessed mother, who by a singular privilege was above the law, nevertheless did not shun being made subject to the principles of the law for the sake of showing us an example of humility.” But Bracton gives this theme a special emphasis, in a specifically legal register and context.

And I would say that the connection is a natural and straightforward one. In the Marian aspect of Bracton’s account, the Digna Vox is the correlate or corollary, certainly the consequence, in the legal and constitutional sphere of Mary’s Fiat in the sphere of political theology. By translating the Digna Vox into not only a Christological register but also a distinctively Marian register, Bracton alludes to and invokes aspects of Mary’s queenly sovereignty, of her public body, that would have been well known to the learned audience of Catholic lawyers to whom his text was primarily or at least partly addressed. Just as Pius XII would later teach that “Mary … has a share, though in a limited and analogous way, in [Christ’s] royal dignity,” so too the prince has a share, though in a limited and analogous way, in hers.

First, the “law” to which the prince professes to be bound is not merely the positive civil law, which is necessarily in part based on the will of the prince himself — a will that may partly rest on arbitrary choice among alternatives, insofar as it represents a specific civil determinatio of more general legal principles.1 It is not merely a case of self-binding to follow the civil law in ordinary cases, itself a choice made by a sovereign will which, in a familiar paradox, can undo that self-binding whenever it wishes. Mary’s Fiat is certainly not a submission to her own will. It is not even precisely (or not only) a submission to the will of God, but indeed to the word of God, the verbum or rhema, a specific determinatio of the logos, spoken on a particular occasion — a perfect fusion of will and reason in application. (Technically of course Mary says secondum verbum tuum, “according to thy word,” the word of Gabriel, but of course this is God’s word, as indeed Gabriel himself said in the preceding verse, at least if verbum is taken literally: quia non erit impossibile apud Deum omne verbum).

Thus the highest attribute of royal and imperial sovereignty is for the Prince to submit himself in ordinary cases not only to the positive civil law (except perhaps where some special cause requires an equitable adjustment or a temporary departure from ordinary civil law ex necessitate), but also, and especially, to submit himself to the commands of natural and divine law.2 Indeed a consistent theme of the imperial jurists is that the particular decrees and enactments of the emperor are always presumed to be consistent with natural and divine law, and may be so interpreted, even if necessary by stretching or bending the letter of those enactments. This sort of beneficent legal presumption wielded by judges, jurists and legal interpreters is one of the main mechanisms for incarnating or embodying the rule-of-law state in the Western legal tradition, long before the advent of liberalism.

Second, just as Mary’s fiat is a perfectly free act, so too the voluntary submission of the prince to the law is the perfection of freedom in the legal sphere. Jared Schumacher said illuminatingly, at least as I understood him, that Mary’s fiat was the most profoundly public act in human history. So too, the freely chosen fiat of the prince, his voluntary submission to the law in what Kantorowicz would call his public and royal body, is likewise the foundational public act of the constitutional order. Here we have three different senses of that complex idea of “constitution”: the fiat of the prince is a constitutio in the Roman legal sense, a decree of the emperor; it is constitutive of the legal order, it creates and composes it; and what it creates is itself a constitution, in the sense of a public pattern of legality that structures the duties and rights of those subject to it, including the prince himself.

Third, the Prince’s fiat draws its creative power from the most profound paradox of Marian sovereignty — brought out by Professor Buttiglione’s comment that “Mary's sovereignty involves a certain inversion of the hierarchies of this world.” For Bracton, the sovereign prince is both the one who has no equal within the realm and yet also, by submitting his public body to the law, places himself in the lower position, the position of those subject to the law. The prince, embodying on a subordinate scale one aspect of Mary’s special honor, indeed has no equal within the temporal order, but not because the prince crushes all others beneath an arbitrary rule. The prince’s fiat is emphatically not merely fiat in the only sense one hears today in positivist legal theory, the arbitrary positive command of a superior will. Rather the reason the prince has no equal in point of honor in the temporal sphere is precisely that, and because, he of all men, the one who could most easily defy and spurn the law, submits himself to the law - the fundamentally Marian fiat that constitutes the legal order.

In this way, even though the prince has no equal in the temporal order, the princely fiat of submission to the law creates a type of equality under the law, yet without leveling the hierarchy of honor in the state. Rather than ruling inferiors by the arbitrary will of a superior, the prince rules according to the very law that binds the subject as well. As the Digna Vox puts it, the prince “forbid(s) others to do what we do not permit ourselves,” and this is itself “the greatest attribute” of princely power, the very attribute that testifies most clearly to the majesty of the ruler.

Indeed, just as Mary provides the prince a type or model of voluntary submission to God, so too in a chain of obligation arising from voluntary obedience, the prince’s obedience to the law provides a model and a kind of possibility theorem for his own subjects, a model for a special category of legal status that has been largely lost to modern constitutional theory: the status of the free subject of a prince. The subject of a prince can be free when, and because, the prince freely submits himself to the law, including natural and divine law, that governs the subject too. The subject in turn freely carries out his duty of obedience to the prince, and indeed makes that obedience the very point and source of honor.

I believe there is only one instance, in the Gospels, of Mary giving something like a recorded command to subordinates: the Wedding at Cana, when she says to the servants: “Quodcumque dixerit vobis, facite” — do whatever He tells you. The Queen, or by translation the sovereign prince, gives many commands to subjects that in essence and in royal archetype are one command, the same command that the sovereign gives to himself: to submit to the word of God the Son, the perfect word that subsumes all modalities of law. And this submission by the subject to the command of the prince, so long as the latter is itself based on submission to natural and divine law, is a form of freedom. As so often, the most clarifying version of this view, both because it is taken to a logical extreme and because it is formulated so memorably, is Dante’s claim that existens sub monarcha est potissime liberum (“to live under universal empire is the greatest freedom”).

A final point about this Marian conception of legality is brought out when we consider Professor Buttiglione’s important distinction between the Marian sovereignty of the nation and the sovereignty of the state. The fiat of the prince makes him the servant of the nation (in the old sense of nation, the people) — makes him the servant of the common good of the whole demos who are also his subjects, thereby embodying the political and dare I say constitutional theory of Matthew 20:25-27: “You know that the princes of the Gentiles lord it over them; and they that are the greater, exercise power upon them. It shall not be so among you: but whosoever will be the greater among you, let him be your minister: And he that will be first among you, shall be your servant.”

As Sister Theresa Marie emphasized, grace perfects and elevates nature. Precisely because and to the extent that the prince’s Marian fiat makes him the servant of the nation, one who rules not for his own benefit but for the common good of the whole — as Sarah Jane Boss discussed — then the prince’s natural potestas, his power, his ability to deploy the force of the state, becomes as it were perfected and elevated in his public body by its participation in the plenitude of grace that is Mary’s auctoritas, her legitimacy as sovereign of the whole nation. In this happy state (pun intended), we have a kind of union of natural power and just authority, of potestas and auctoritas. The prince as public office is sanctified, whatever the state of the prince’s personal and individual body and soul. Needless to say, this is a regulative ideal that is not always achieved.

The unhappy alternative occurs when this union is not achieved or sustained, when potestas and auctoritas are divorced one from another. Pascal described the unhappy consequences of this divorce in the following terms: la justice sans la force est impuissante; la force sans la justice est tyrannique (justice without force is powerless; force without justice is tyrannical). The Marian fiat of the prince thus heals the alienation or split between nation and state that Poland suffered under the external domination of Swedish soldiers or of Communist forces, to mention examples discussed at the conference.

With Bracton’s Marian conception of the rule of law sketched, let me elicit an important implication of his conception — an implication for the relationship between the rule of law, one the one hand, and the form of the constitutional order and political regime on the other. As I do so I will implicitly wink at my friend Hans-Martien Ten Napel, for as you will see, I will develop, among other thoughts, the thought that “Christian Democracy” is neither a contradiction in terms, nor is it one unitary political stance. Rather, on a third view, Christian Democracy is an uneasy and always contingent combination of two things, sometimes in the right relationship to one another and sometimes not, just as liberal democracy is two things always in an uneasy and contingent, sometimes conflicting, mutual relationship.

The Bractonian conception of the rule of law I have sketched provides a framework for law and constitutionalism, not a blueprint of prescriptions for this or that particular constitutional order or set of particular institutional arrangements. Different polities with different histories, traditions, and cultures adopt different determinations of the political order, subject to the master principles that law and constitutionalism be ordered to the common good of the polity as a whole, and that law properly so-called should conform and should where possible be interpreted to conform to background traditional principles of legal justice, including natural law, which are themselves binding and internal to the law. Within these constraints, the classical legal framework of the rule of law is agnostic; it can be and has been applied to and within empires, national monarchies, republican or aristocratic city-states, and democracies in the modern sense, with all of these varying on the form and quantity of public participation they allow.

For the classical lawyer, the question which form of government is best cannot be answered absolutely and universally. Rather it has to be answered in relative terms, for a certain range of conditions in any given polity, depending upon the culture, history, traditions and circumstances of that polity. The rule of the many can be well-ordered to the proper ends of the state, the common good under natural and divine law, but can also be authoritarian or even tyrannical, just as the rule of one or few may be.

For that reason, classical constitutional theory, as I have explained, does not in fact believe that “democracy,” let alone the uneasy combination of 20th-century views that goes under the label of liberal democracy, has any intrinsic value, if by that we mean that a particular institutional technology for public participation is best in all times and all places, for any polity. The classical view is perhaps best summarized by John Paul II in Evangelium Vitae: “Democracy is fundamentally a ‘system' and as such is a means and not an end. Its ‘moral' value is not automatic, but depends on conformity to the moral law to which it, like every other form of human behaviour, must be subject: in other words, its morality depends on the morality of the ends which it pursues and of the means which it employs.” Democracy too, in order to become itself, must enact Mary’s Fiat by submitting to natural and divine law, or it becomes something else, something tyrannous. Democracy that is not at least implicitly Christian, strictly speaking, does not exist, except in the qualified form that a perverse and tyrannous law can be said in some sense to exist. Democracy that is not Christian, that insists on remaining in its natural state and refuses to be perfected and elevated by the plenitude of grace, will inevitably decay into something else entirely — not even authentic democracy at all. I believe that we have witnessed this process of decay in versions of Christian democracy that, in our own time, have become less and less Christian even as they claim to be, albeit in a perverse sense, more and more “democratic.”

As John Finnis emphasizes when he refers to “a determinatio of principle(s)—a kind of concretization of the general, a particularization yoking the rational necessity of the principle with a freedom (of the law-maker) to choose between alternative concretizations, a freedom which includes even elements of (in a benign sense) arbitrariness.” https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/natural-law-theories/

Of course, it should go without saying that the willing obedience of the prince to the rule of law (the law’s vis directiva) is not the same as obedience to review by courts or any other external entity (the law’s vis coactiva). The availability, or not, of judicial review is a separate question and one that is left to the determinatio of particular constitutional polities. See an illuminating exchange between Michael Foran and Jamie McGowan on these questions.

This approach to sovereignity and the simultaneous ability to impose law, but also be subject to it, creates coherence that modern liberal rule often overlooks, where invocation of the sovereignty of the nation creates an exception for rule that is often not subject to laws it creates.

This moral gap and absolutism of modern political systems ends up creating far less freedom than people perceive to have.

I found this article surprisingly... moving. The realm of political and constitutional theory can be very high-level and abstracted. It's beautiful and rational in its own way, but often lacking in poetry and theological imagery.

The image of Mary as sovereign, giving her fiat freely in submission to the Divine Word, prefiguring Christ who himself freely submits to a position lower than his nature requires, and this being the example of excellence, the requirement for a just ruler, is at once so obvious and powerful that it feels like it's something I've known forever. It's a beautiful image for a complicated question. It has more explanatory power in its imagery than it does in words. It feels like something that we can chew on for centuries.

One observation: It seems that in all three cases, the sovereign is freely binding to something which is not strictly required. Christ bind's himself to the Divine Will to take on human nature (and further, to the Mosaic Law). Mary binds herself to the Word of God to bear a son (and further, to the Mosaic Law). And the prince binds himself in a legal sense to the Divine and natural law (and further, to civil law).

Surely the prince is always bound to divine and natural law (just as Mary), but not in a legal sense -- as sovereign, there are none to hold him to account, no apparatus of state above him; he is immune. And further, it seems there may be some parallel between what the Mosaic Law was for Christ and Mary to what the civil law is for a prince. Something additional that they choose to be bound to, though they are in no real way required to be, for that law is purely for the subjects, not the sovereigns.