A deeply impressive legacy of the classical legal tradition was the capacity of its leading jurists to convincingly reconcile two competing imperatives of good government: how to both empower and constrain the State so that it is ordered to the common good

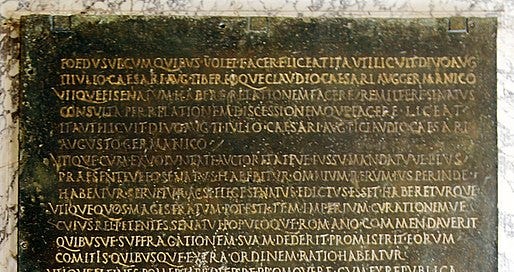

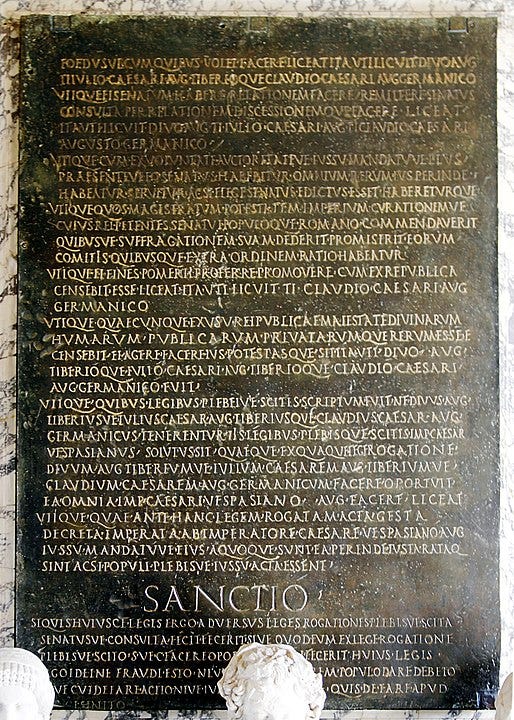

The great texts of Justinian’s Corpus Juris Civilis – the Digest, the Code, the Novels – stress how lawmakers and officials should be vested with ample authority and power so that they might efficaciously pursue the public good. One of the most famous precepts in this vein was the lex regia, used by jurists as a compendious legal concept to capture the effect and consequence of the wholesale transfer of the Roman people’s natural imperium and potestas to govern themselves to the office of Roman Emperor, who became vested with plenary authority and power (auctoritas and potestas) to uphold peace and justice for the public good. The lex regia was the font of other famous precepts like the Emperor being the living voice of law and justice; that whatever pleased the Prince had the force of a statute (quod principi placuit legis habet vigorem); and that the Emperor was not bound by the civil law nor answerable to any higher authority in the exercise of his functions (princep legibus solutus). The Emperor was invested with authority to make and unmake laws for the public good of the people, and to render justice and enforce the law, and final say on the adjudication of disputes. In some writings the prince’s office was described as ‘law incarnate’ and the prince the father and font of justice in the polity.

This will be extremely distasteful for those who see constitutional law’s primary role as being a bridle on political power and bulwark of individual liberty against the political community. But while it is fair to say the classical tradition is comfortable with strong, purposive, rule and a robust executive, it is beyond caricature to say it endorses absolutism. Because an equally bedrock principle of the tradition is that public power is inherently reasoned and purposive – to be exercised by princes and lawmakers and executives for the public good, and not arbitrarily or tyrannically. The whole point of public law in this tradition, after all, is to constitute, empower, and channel the workings of political institutions to promote what Cicero dubbed the utilitas rei publicae - the ‘public advantage’ - of a commonwealth and its People.

How, then, to reconcile these competing impulses? How to ensure vesting considerable authority and power in officials did not merely promote the use of discretion for private, factional, and tyrannical ends? In the classical tradition, reconciliation between the different structural imperatives of public law was partly achieved by articulating another critical principle of legal justice: that those administering justice according to law were entitled and required to treat legal propositions enacted by lawmakers as strongly presumptively oriented towards justice and the common good.

Adages like “Quod principi placuit” that at first glance smacked of absolutism were, in fact, understood by classical commentators of the ius commune tradition against the rich conceptual backdrop of several additional principles. One principle, observed the classical Italian jurist Baldus de Ubaldis, was that “nothing is presumed to please the emperor except what is just and true … and the emperor wishes all his actions to be ruled by divine and natural justice as well as human.” While the prince might not be subject to the coercive force of posited law, or liable to be dragged before a tribunal or assembly by inferior officials, their duty to promote the common good meant they could not act contrary to the rule and measure of genuine human good and flourishing in community – the natural law. As Aquinas put it similarly in his Treatise on Law, the “Quod Principi Placuit” principle should be understood be jurists to mean that all their ordinances will be guided and informed by right reason and the natural law. Otherwise, maintained Aquinas, those same ordinances would have more of the character of iniquity and violence than law simpliciter. Elsewhere, Aquinas wrote that where adhering to the “letter” of an ordinance would contain anything contrary to “natural right”, judgment should be instead delivered consistently with “the equity which the legislator intended” or “common benefit” the “lawgiver intended to secure”. Strongly implicit in Aquinas’ prescriptions is a standing legal presumption that the lawgiver should not be understood to intend to act contrary to the “common welfare of men”. The mainstream ius commune position was both that the notion of legibus solutus only applied to civil positive law and not to higher norms of natural and divine law, and that the intent of the lawmaker in enacting civil laws should strongly be presumed to serve the commonweal.

Another well-embedded principle was that it was presumed it pleased the prince to act after due and careful consideration and consultation with his learned officials and jurists about what ought to be done for the common good, and therefore not capriciously, impulsively, or in a fit of pique or passion. Alfonso X’s mirror of princes - the Siete Partidas - emphasises that the prince should take careful counsel from his prelates and men learned in the law before issuing ordinances. Bracton’s Treatise on the Laws and Customs of England was similarly confident it was presumed what pleased the prince would emerge, not arbitrarily or in a fit of pique, but as a product of debate and deliberation with the great men of the kingdom.

Finally, it was widely regarded as befitting the dignity of the prince that they subject themselves to the same laws they promulgate for the good of their people, and it was presumed that when acting they would not do so contrary to existing lex or custom (where the latter did not conflict with natural law). This was for several reasons. One was recognition that ultimately it was the law – for example the lex regia – that constituted the office held by the ruler and granted them authority in the first place. Another was an acknowledgment that the willy-nilly breaking of posited law, which were regarded as reasoned ordinances for the common good, could be regarded as a sign the ruler was misfiring in their role, by acting according to their passions and desires and not reason or the public good. In other words, a ruler that paid scant regard to the integrity of posited law was more prone to slide into rule for their own benefit – the classical definition of tyranny – and in extremis lose the right of obedience of their subjects.

To tie these principles together, it was a generic, bedrock, assumption of the classical legal tradition - one running concurrent with the notion princes, lawmakers, and officials are vested with capacious authority to secure the common good – that the lawmaker is strongly presumed not to wantonly violate background principles of ius and norms of reason that are constitutive of the nature of law. As Professor Helmholz has shown us in Natural Law in Court, this interpretative attitude was not some lofty academic ideal, but deeply woven into the fabric of legal practice in Western Europe. The working assumptions of lawyers and judges, says Helmholz, led them to try and interpret and harmonize posited law and natural law insofar as possible. They did this, for example, by presuming that a statute could not have been intended to reach a result that contained either absurdity or iniquity and that the lawmaker did not intend to allow their directives to conflict with justice and the common good.

You don’t have to look very hard to see the continuing influence of such principles in contemporary law. It can be found in the most bread and butter of legal doctrines in many jurisdictions, like the presumption of constitutionality, the presumption against retroactivity, the presumption that discretion will be used for a public purpose and not for private gain, and the generic presumption of statutory interpretation the lawmaker is a reasonable actor pursuing reasonable ends reasonably. All are built on the distinctly classical premise the lawmaker is an office that exists for a reason – to promote the public good - and that all its activities should be presumed to be discharged consistent with this purposive end. This starting point helps explain why the attitude and presumptions of the jurist often differ sharply indeed from those of the historian or political economist.

Classical jurists today should seek to adapt and translate Roman law and classical legal precepts to forge still more ambitious doctrinal principles stemming from respect for immutable principles of legal justice. One that comes to mind is for jurists to presume, as was common within the ius commune tradition, that all legislation and statutory discretion granted under statute will be exercised in light of right reason, and that this presumption imports respect for basic precepts of the natural law where they are engaged. Today we might include here respect for human life at all stages of development or vulnerability, subsidiarity, solidarity, the marital family, public order and peace, and truth, including ultimate truth and the liberty to pursue and live according to it.

For a more full-length treatment of these issues, see my forthcoming essay here