The common good is the only purpose of the Government - Juan Germán Roscio

On September 26th 2023, Professor José Ignacio Hernández published an essay with The New Digest exploring the links between U.S. constitutional law and the European institutions influenced by the classical ius commune. He documented how John Adams studied the classical tradition with interest, especially in Spain, which Adams visited in 1780. And he argued that for Adams, the U.S. Constitution derived its content from the "simple principles of nature." Those were the same principles that inspired the ancient fueros and early constitutionalism in Hispanic America, which Adams discussed in his 1787 work A Defence of the Constitutions of Government of the United States of America. That is, the principles were rooted in the classical legal tradition, according to which the constitutional foundations of the government are based on the common good.

On 17th October 2023 the New Digest hosted a reply to Professor Hernández’s essay by the Spanish lawyer and legal theorist Aníbal Sabater. In his reply Sabater argued that Professor Hernandez is certainly right that for centuries Spain had a constitution based on traditional institutions favoring subsidiarity and ordered towards the common good. But Sabater cautions that the “unwary reader, however, may … conclude that the 1812 regime did nothing but to confirm that constitution, albeit with some textual reorganization. Not really.” Sabater argued that the Spanish Constitution of 1812, also known as the “Cádiz Constitution” after the city where it was drafted, was actually liberal in form and substance.

In this post Professor Hernandez offers a reply that continues the conversation with Sabater on the role of liberalism in Spanish constitutionalism. The New Digest is pleased to host this discussion between two such outstanding jurists.

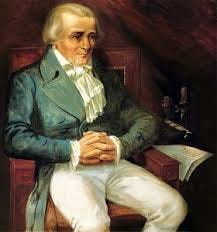

Based on a previous post in which we studied the interpretation of the Spanish Ancient Constitution by John Adams, Aníbal Sabater wrote an essay that accurately explains the tensions between the Ancient Constitution and the liberalism that inspired the Cádiz Constitution. This reflection is the best introduction to explain the tensions between Constitutional Law and liberalism from the perspective of the Venezuelan scholar Juan Germán Roscio.

*

Juan Germán Roscio (1763-1821) was a legal scholar who actively worked in Venezuela's constitutional foundations, including its 1811 Constitution -the first Constitution in Spanish that, at the national level, followed the U.S. Constitution principles-. The Constitution, however, collapsed in 1812, and Roscio was arrested and deported to Spain and later to Ceuta. He escaped and traveled to the U.S. Simón Bolivar asked Roscio to return to Venezuela to collaborate with Venezuela's independence. Still, Roscio has a more compelling task: publishing the book he wrote in prison.

Roscio understood that one of the reasons for the collapse of the 1811 Constitution was the Catholic doctrine, which was interpreted against the foundations of independence and in favor of the divine rights of kings. According to this interpretation, Independence was not only a sin but a threat to the virtues that would collapse due to licentiousness.

The fight for independence, according to Roscio, should occur not only on the battlefield but also in the people's minds. In pursuit of this objective, it was deemed essential to elucidate that the Catholic doctrine upheld the principles of Venezuela's independence and the concept of freedom within the bounds of the Law.

That was the topic of the book Roscio wrote in prison, published in Philadelphia by Thomas H. Palmer in 1817: The Triumph of Liberty against Despotism. As I have explained elsewhere, Rocio’s book helps to understand how liberalism was conceived from the incipient Constitutional Law in the Hispanic Law.

**

Guerrero, Leal, and Plaza have studied how the constituent moment in Venezuela (1810-1811) helped to redefine the expression “liberalism”. Originally, liberal was used to describe morally dubious actions or licentiousness. But since 1811, liberalism was redefined to refer to the Democratic Republic. As Pedro Grases explains, liberal expression was widely used during the debates of the Cortes de Cádiz to describe the new political ideas aimed at refraining from the abuse of power.

“Liberal” was a contentious expression that summarized one of the main concerns of the constituent process that started in Venezuela in 1810: how to build a representative Government without disrupting the colonial order. As a result, and following Germán Carrera Damas, the 1811 Constitution combined "liberal institutions" (the separation of power) with colonial ones (Catholicism as an official religion).

The central theme of Rocio’s book revolves around the tension between liberalism and representative government. Opponents of independence contended that liberal ideals clashed with the tenets of the Catholic faith, going so far as to interpret the devastating earthquake that nearly destroyed Caracas in 1812 as a divine retribution. Roscio penned his work to prove not only that Catholicism did not stand in opposition to ideas of political independence but also that there existed no inherent contradiction between liberal principles and the constitutional order. In pursuit of this objective, he drew upon the foundation of the classical legal tradition.

The starting point in Rocio's thought was to define freedom. In Chapter XVI, Roscio explained that "political freedom is not the licentious free will to do what each one wants, even if it is contrary to natural and divine laws." Freedom is the right to act with autonomy but under the limits of the Law adopted by the people's representatives. To define Law, Roscio added an important criterion: "What is not just does not deserve the name of Law, whose essence consists in being a right sanction, which orders what is good and prohibits what is bad, as Cicero defined." The obedience to the Law, thus, cannot be blind because the Law can be an instrument of oppression. On the contrary, obedience to the Law should be based on reason to distinguish between the Law "that lacks this intrinsic goodness" and the fair Law enacted to promote the common good (Chapter XXIX).

In Chapter XVI, Rosio argued that “for the common good, men pledged to live together in various demarcations: for the prosperity of all, they agreed to the organization of a government”. The common good “justifies the conduct of those who, adorned with virtue and corresponding talent, venture to the risks of the government”. (Chapter XLIV).

Freedom, thus, is the “power to execute all that which is not prohibited by natural and divine law or by the general will of the people". The people's general will is a positive law (lex) that cannot be separated from the natural law and its fundamental principles (jus). Positive law emerges through the deduction of those principles. Consequently, no liberty exists to contradict these principles, and any positive law conflicting with them cannot be considered legally binding. Any abuse “of individual freedom that goes against them, has to be repressed by national force, and in the manner prescribed in this public Law” (Chapter XVII).

Roscio employed the term "liberal" to characterize a political system structured around pursuing the common good grounded in human dignity. According to this concept, there is no inherent conflict between freedom and Government, as freedom can only thrive within a governance framework dedicated to serving the common good. Rocio’s vision of Constitutional Law did not prioritize freedom over the Government; rather, the Government was not perceived as a threat to be averted but as a necessary institution governed by a rational order of rules, principles, and values rooted in the pursuit of the common good.

Therefore, Constitutional Law prevents not only the Government´s abuse of power but also the abuse of individual freedom. The Venezuela 1811 Constitution -drafted by Roscio- differentiates between the unlimited and licentious freedom led by passions of the "savage state" from the freedom within the Law, more “sweet and pacific”, and subject to “certain mutual duties” (Art. 141). Liberty was defined as the "faculty of doing everything that does not injure the rights of other individuals or the body of society" (Art. 153). To summarize this idea, inspired by the 1780 Massachusetts Constitution, Roscio defined, in the Constitution, that Government is instituted for the common good.

***

Regardless of the tensions between the liberal ideas and the Cádiz Constitution, Roscio interpreted the 1812 Constitution following the ancient constitutional roots of the Government based on the common good. For Roscio, the Cádiz Constitution was liberal, not because it exalted freedom over Government, but because it embedded a constitutional system founded in the popular sovereignty limited by the common good.

Following Rocio's ideas based on the ius commune tradition, we can better understand the expression liberal democracy, which is used as a synonym for constitutional democracy. In this context, "liberal" does not convey a sense of libertarianism, advocating for a Government strictly confined to minimal tasks. Nor does it align with the unrestricted expansion of individual freedom akin to constitutional progressivism. According to Roscio, the Cádiz Constitution was deemed liberal because it established a political system wherein sovereignty resided in the people, albeit constrained by natural principles and values entrenched in the ius commune tradition.

From a Constitutional Law standpoint, as encapsulated by Graciela Soriano in her overview of Manuel García Pelayo’s works, liberalism can be interpreted either from an individualistic stance that opposes Government or through the lens of liberalisms founded on human dignity, achievable only when the Government is subordinated to the Constitution. Precisely, Roscio comprehended that liberal constitutionalism posits the necessity of a Government established for the common good to safeguard freedom, rooted in rights and corresponding duties, by the principles and values inherent in the ius commune tradition.