John Adams, the Ancient Spanish Constitution, and the Ius Commune

The Hispanic Origins of U.S. Constitutional Theory

The New Digest is pleased to present a guest post by José Ignacio Hernández, Center for International Development, Harvard Kennedy School.

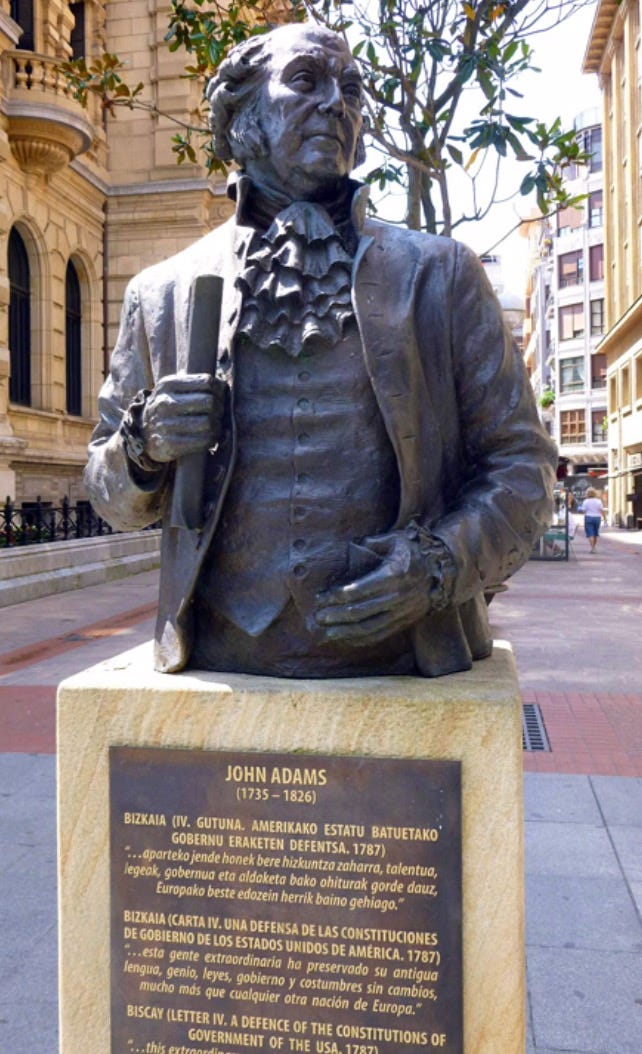

— Statue of John Adams in Bilbao, Spain

On November 13, 1779, John Adams departed - for the second time in a short period - to Paris to negotiate a peace treaty with Great Britain as minister plenipotentiary of the Continental Congress. “I had again the melancholy”- wrote Adams in his diary - of “taking Leave of my Family, with the Dangers of the Seas and the Terrors of British Men of War before my Eyes”.

Adams' concerns were proven correct. On November 25, Adams wrote that due to a leak in the Sensible, the Captain decided to deviate to Spain, specifically to “Ferrol or at least of Corunna". On December 8, they arrived at El Ferrol, and decided to travel by land to France across northern Spain. As Richard L. Kagan explains, Adams followed -although in an opposite way - the Camino de Santiago. On January 23, 1780, Adams and companion - including John Quincy Adams - arrived at Bayonne.

During his unplanned and perilous trip in Spain, Adams observed the particularities of the political institutions he later used in his 1787 A Defence of the Constitutions of Government of the United States of America. Chapter I of the first Volume of this work was dedicated to "Modern Democratic Republics", including Biscay. In this section, Adams analyzed the political institution of what is known as the Spanish ancient constitution, including the fueros, to compare those institutions with the U.S. Constitution.

The comparative constitutional law exercise by Adams helps to understand better the interlinks between the U.S. Constitutional Law and the European institutions influenced by the ius commune.

The ancient constitution in Spain, the fueros, and Hispanic constitutional foundations

Although the first codified Constitution in Spain was approved in 1812 as part of the Hispanic-American Revolution, there was a constitution - or ancient constitution - based on fundamental political institutions. Agustín Arguelles, in his Preliminary Remarks on the 1812 Constitution, summarizes this vision as follows:

“The draft Constitution offers nothing that has not been established in the most authentic and solemn way in the different bodies of Spanish legislation, but rather the method that has distributed the matters, ordering and classifying them so that they form a system of fundamental law is seen as new and constitutive in which it is contained with connection, harmony, and concordance as provided by the fundamental laws of Aragon, Navarra and Castilla”

A vital component of the ancient constitution is the fueros, a traditional form of self-government subject to it owns rules and traditions. The fueros were, then, local juridical orders protected from any external intervention, and as a result, they were considered a privilege or, more precisely, an exceptional framework. For instance, the Biscay fueros were not only a special juridical order but a privilege that protected Biscay from any intervention of any other political community, such as Castille.

Due to its local nature, the fueros prevented legal unification, a work that was advanced by Alfonso X, el Sabio, king of Castille (1221-1284). Alfonso - considered a modern Justinian - advanced a legislative compilation, including El Fuero Real, but mostly, the Siete Partidas. Following Antonio Pérez Martín, a source of that compilation was the European ius commune, in a similar way to the Liber Iudiciorum.

There were, then, fundamental and traditional institutions in Spain that evolved from the municipal fueros to the general legislative compilations inspired by the ius commune. Notably, this ancient constitution was invoked to justify the independence processes of the early 19th Century. For instance, the Declaration of April 19, 1810, approved in Caracas (at the time, part of the Venezuela General Captaincy), invoked the sovereign rights that, as a result of the captivity of Fernando VII, were reassumed by the people "in accordance with the same principles of the wise and primitive Constitution of Spain”.

As I have explained elsewhere, the Venezuelan Constitutional scholar Juan Germán Roscio, in the Chapter XLIII of his 1817 book El Triunfo de la Libertad sobre el Despotismo, examined the ancient constitution to explain and justify Venezuela's independence and the 1811 Constitution approved by the "Venezuelan States". Roscio - in Chapter I of his book - summarized those ancient institutions, concluding that "the common good is the only justification of all the governments". Not surprisingly, that idea was reflected in the early Constitutions approved in Hispanic America during the 19th Century, including the 1811 Republic of Tunja Constitution (currently Colombia).

Adams' observations about a tempered democracy based on the fueros

Adam's diary has many commentaries about the customs and political institutions that he observed during his trip alongside the Biscay Bay, including the fueros. On December 14, 1779, Adams observed that “The ancient Laws of the Visigoths are still in Use, and these, with the Institutes, Codes, Novelles &c. of Justinian, the Cannon Law and the Ordinances of the King, constitute the Laws of the Kingdom of Galicia”.

On December 19, Adams engaged in a conversation about the American forms of Government, offering to translate the Report of a Constitution or Form of Government for the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, adopted shortly after. Interestingly, as we will see, these documents - the basis of the Massachusetts Constitution - have several mentions of the common good.

Adams arrived in Biscay on January 13, 1780. In a report to the Congress dated January 16, Adams summarized the essence of the fueros as follow:

“It may seem surprising, to hear of free Provinces in Spain: But such is the Fact, that the High and independent Spirit of the People, so essentially different from the other Provinces, that a Traveller perceives it even in their Countenances, their Dress, their Air, and ordinary manner of Speech, has induced the Spanish Nation and their Kings to respect the Ancient Liberties of these People, so far that each Monarch, at his Accession to the Throne, has taken an Oath, to observe the Laws of Biscay”

Those Ancient Liberties were, indeed, the fueros. Some years later, in A Defence of the Constitutions of Government of the United States of America, Adams analyzed the U.S. Government considering Cicero's reflection on the republic as the res populi founded in the consensus under the Law - iuris consensus- and based on the common utility -utilitatis communis. Consequently, the republican form of Government was not a simple democracy because "a simple and perfect democracy never yet existed among men”.

Adams preferred, then, to analyze the U.S. Government as a democratic republic, in which the res populi was tempered by the utilitatis communis, providing some examples of such modern democratic republics, including Biscay - the region that he visited some years before. Adams refers to the fueros as the “great immunities" of Biscay. Those immunities were based on a democracy but a tempered one. As Adams observed:

“Thus we see the people themselves have established by Law a contracted aristocracy, under the appearance of a liberal democracy. Americans, beware!”

For Adams, the fueros provide a democratic government “tempered with aristocratical and monarchical powers”.

The common good clause in the 1780 Massachusetts Constitution: the missing link in U.S. Constitutional Law?

During his journey in Spain, as we explained, Adams commented on the Report of a Constitution or Form of Government for the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. In that document, we can identify traces of the concept of a tempered democratic republic founded on the common good:

“The body politic is formed by a voluntary association of individuals: It is a social compact, by which the whole people covenants with each citizen, and each citizen with the whole people, that all shall be governed by certain laws for the common good."

That idea - as reflected in the report - inspired Art. VII of the 1780 Massachusetts Constitution, which, as explained, inspired early Hispanic American constitutionalism.

Adams was aware of the common good expression before his journey in Spain, as demonstrated in the report. However, his unintended travel through Biscay Bay provides Adams with an example of a government instituted for the common good: Biscay and its ancient constitutional values reflected in the fueros. That example was used by Adams to interpret - and justify - the U.S. Constitution.

This evidence supports Adrian Vermeule’s thesis, according to which U.S. constitutional law is inspired by the classical legal tradition and the ius commune, which imply that the common good is a constitutional value.

John Adams would probably agree with that thesis because he compared the U.S. Constitution with Biscay, that is, a democratic republic based on tempered democracy, as reflected in the fueros. For Adams, the U.S. Constitution derived its content from the "simple principle of nature". Those were the same principles that inspired the ancient fueros and the early constitutionalism in Hispanic America. That is, the principles rooted in the classical legal tradition, according to which the constitutional foundations of the government are based on the common good.