The New Digest is delighted to feature this guest post from Aníbal Sabater. Mr Sabater is a lawyer in New York City specializing in international arbitration.The author is grateful to Rafael de Arízaga for his very perceptive comments to an earlier draft of this piece.

In his illuminating essay on “John Adams, the Ancient Spanish Constitution, and the Ius Commune,” Professor José Ignacio Hernández includes the following paragraphs:

“Although the first codified Constitution in Spain was approved in 1812 as part of the Hispanic-American Revolution, there was a constitution - or ancient constitution - based on fundamental political institutions. Agustín Arguelles, in his Preliminary Remarks on the 1812 Constitution, summarizes this vision as follows:

‘The draft Constitution offers nothing that has not been established in the most authentic and solemn way in the different bodies of Spanish legislation, but rather the method that has distributed the matters, ordering and classifying them so that they form a system of fundamental law is seen as new and constitutive in which it is contained with connection, harmony, and concordance as provided by the fundamental laws of Aragon, Navarra and Castille’

A vital component of the ancient constitution is the fueros, a traditional form of self-government subject to it owns rules and traditions. The fueros were, then, local juridical orders protected from any external intervention, and as a result, they were considered a privilege or, more precisely, an exceptional framework. For instance, the Biscay fueros were not only a special juridical order but a privilege that protected Biscay from any intervention of any other political community, such as Castille.”

Professor Hernández is certainly right that for centuries Spain had a constitution based on traditional institutions favoring subsidiarity and ordered towards the common good. The unwary reader, however, may take the quote from Agustín Argüelles at face value and conclude that the 1812 regime did nothing but to confirm that constitution, albeit with some textual reorganization. Not really.

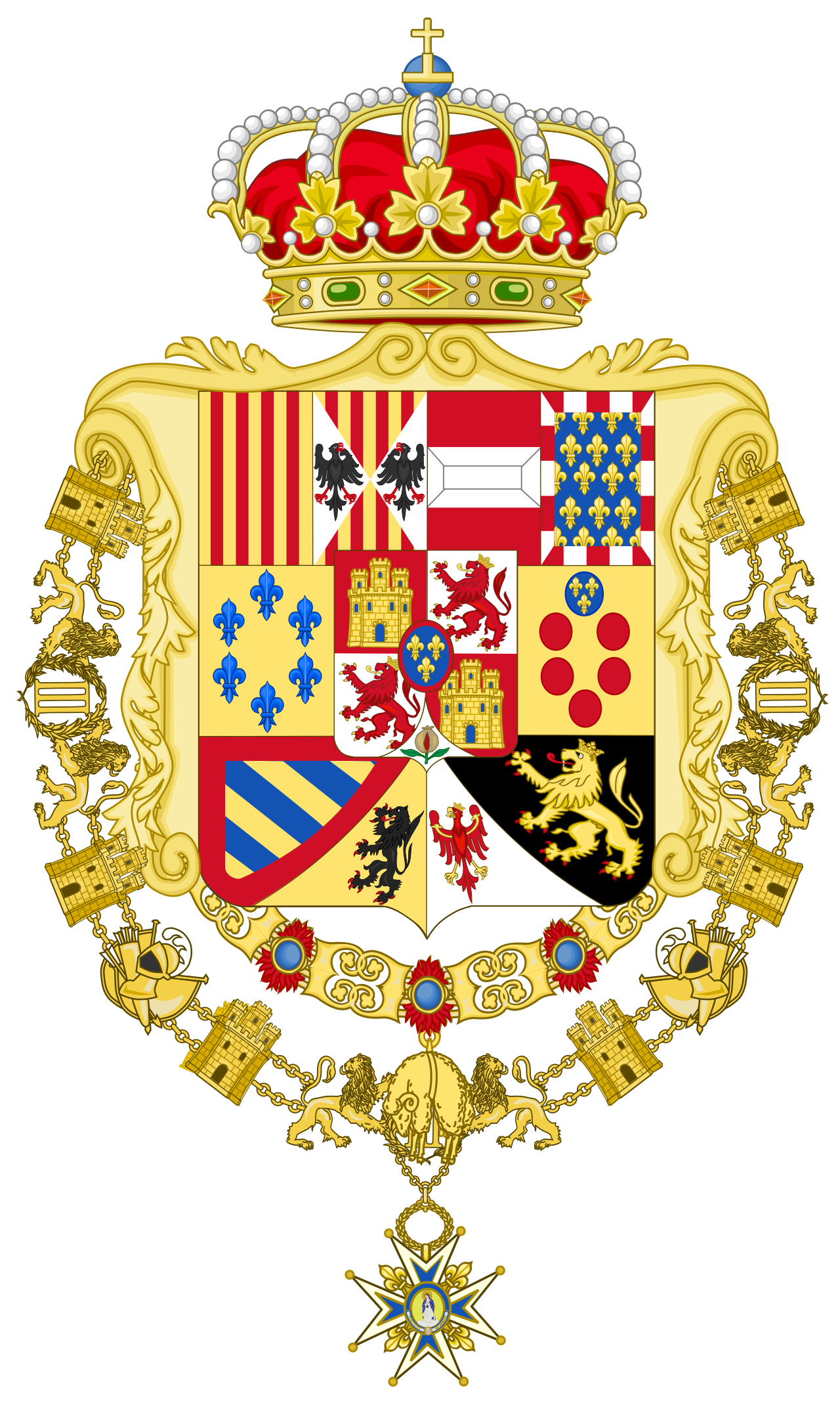

The Spanish “Constitution” of 1812, also known as the “Cádiz Constitution” after the city where it was drafted, was liberal in form and substance. Its genesis is best explained in a 1814 Manifesto to Ferdinand VII, King of Spain, penned by politicians supportive of the ancient institutions. The liberals, who liked to portray the classical Monarchy as a fealty of satraps, derisively called it the Persian Manifesto (“Manifesto de los Persas”).[1] The name has stayed, but so has the relevance of its analysis.

First, the Manifesto explained how Spanish traditional monarchy (sometimes ambiguously dubbed absolute) operated:

“Absolut monarchy (a term that is excessively used among the people with much equivocation) is a work of reason and intelligence: it is subordinate to divine law, justice, and the fundamental rules of the state … Accordingly, the absolute Sovereign cannot use his authority without good reason (a right that not even God wanted for Himself): this is why Sovereign power is absolute, so as to prescribe to his subjects all that is necessary for the common good … Those who claim against absolute power mistakenly take it for arbitrary; they fail to realize that there is no state, not even republics, where there is no absolute power underlying sovereignty. The only difference between the power of a King and that of a Republic is that the former can be limited whereas the latter cannot … In an absolute government people are free, property of goods is legitimate and inviolable, such that it can be enforced even against the Sovereign himself, who can agree to be compelled to court … There are certain covenants between the Prince and his People that are renewed when a new King is consecrated; there are laws, and whatever [may be done] against them is null. The Sovereign cannot freely dispose of the life of his subjects, but must conform to the order of conduct provided for in the state ….

The wisest politicians have preferred this absolute monarchy to any other form of government. Man in this monarchy is no less free than in a Republic; and tyranny is much more to be feared in the latter than in the former ….”[2]

Far from utopianism, however, the Manifesto acknowledged that the ancient constitution had not always been peacefully applied. In particular, in the mid-16 century, the ministers of King Carlos I (Holy Roman Emperor under the name of Charles V) tried to by-pass ancient institutions such as the fueros or the Cortes, a key legislative body. The Castilians rose up in arms in defense of their traditions, but the question was not fully settled and tensions between the ancient constitution and attempts at tyranny continued over the centuries:

“Carlos I brought about the beginning of some despotism from the ministers, such that the Constitution of the realm started to suffer. This caused the civil of the war of the communities [and] a decrease in the authority of the Cortes [an ancient legislative body] ….”[3]

The Bourbons acceded to the throne in the 18th century and brought along a French-inspired strain of enlightened despotism that encroached further on the ancient institutions, derogated some fueros, and centralized decision making. While most of the traditional laws of the realm stayed unaltered on paper, the application of some of them became erratic and despotism generated discontent on which a nascent liberalism was quick to capitalize:

“His Majesty has been a witness of the despotism of the ministers in recent times, and it pains us to add that he has been a victim of it. This would not have happened if the laws, the Cortes, and the praiseworthy customs and fueros of the past had kept their old vigor. Because of this situation, it has been easy for the populace to believe that this Cádiz Constitution is the only remedy to cure its pains, which were rather caused by the lack of an administration of justice, the failure to observe [our] fundamental laws and the escape the advice and control of the Cortes. All these abuses have been of incalculable consequence.”[4]

Then in 1808 Napoleon occupied Peninsular Spain and held King Ferdinand VII hostage in France. At that point, the liberals decide to move to action. Only the King could convene the Cortes, let alone a constitutional assembly, but Argüelles and other liberals of prominence in the provinces managed to call for on their own a popular “constitutional assembly” of sorts to take place in Cádiz. In addition to the timing, the liberals were also careful to choose the composition of the meeting—most Spanish territories on either side of the Atlantic were precluded from sending representatives.

Predictably, the key question posed to the “assembly” was not whether to maintain the ancient constitution, but rather whether the integrity of power should be construed to lie with the “people,” as the concept had been understood in the French Revolution, or stay with a cabinet of enlightened despots, the King’s ministers.

Of course, the “assembly” approved a “Constitution” providing that “Sovereignty lies essentially in the Nation and for this very reason the right to establish its fundamental laws belongs to the Nation alone” (the “Nation” being previously defined as “the assembly of Spaniards from both hemispheres.”). This created the fiction of a sovereign body unanswerable to a higher authority—an immanentized community, which would no longer serve an end beyond itself. It also heralded the definitive suppression of the fueros system, with its emphasis on subsidiarity and primary forms of association like the family, village, or guild, who were now required to make room for the “Nation.” Indeed, the “federative” and imperial nature of the Spanish Monarchy, which held together various kingdoms and territories—each with its own laws and identity—under a single ruler and a single faith, and which had already been somewhat softened under the Bourbons, was altogether elided at Cádiz. It is difficult to imagine a more radical departure from the ancient the Spanish constitution—and many at the time realized it.

Fr. Magín Ferrer, a Mercedarian priest and author of the reference treatise on the Fundamental Laws of the Spanish Monarchy (1843),[5] had this to say about the “Cádiz Constitution” and Argüelles’ preliminary remarks to it:

“Another way to abuse the credulity of irreflexive men has been to make them assume that establishing a representative government would restore the ancient laws of the Monarchy. Many suffered from hallucination caused by [Argüelles’] Preliminary Remarks to the Constitution of 1812 and by the Introduction to the Statute of 1834. One need only read those codes to realize that they abused the name of the venerable fundamental laws as if to make them accomplices in the unjust and monstruous innovations that these codes meant to introduce. Those men would have never entered a constitutional system had they known that what they were being offered was neither true, nor just, nor legal. Many have since realized the truth, but may still ignore the actual remedy to cure all the evil done by those bastard codes. Surely those men think that there is no middle ground between joining the deceptive way of a representative government and falling prey to a despotic King … But when one comes to think of it, there is a middle way between the extremes of the representative government, which in the end is just a republic as I will show later in this work, and a despotic Monarch, whose only law is his will and acts independently from natural law and the usages and customs of the land, which in a way are already fundamental laws before these laws are written. That middle way is the restoration of the true fundamental laws of the Monarchy, with whatever updates they may need. I do not mean updates from new lights obtained this last century, which has not yielded any progress in legislation, but updates to adjust those laws to the times, to the current situation of Spaniards, and the variations that have followed the unification of crowns, and other natural and political events, which quite often alter the laws, irrespective of the will of men.”[6]

In a nutshell, pace Argüelles, the Cádiz regime did not intend to preserve the traditional constitution, but to bury it, which he obviously knew given his involvement in the entire drafting process. But then, why did he lie? The answer can be found in the idiosyncratic way in which liberalism operated initially in the Spanish speaking world—by being coy about its ends but adamant about its means. Even if insufficient to obtain complete victory, the strategy would prove massively effective at weakening the staying power of the ancient order, a lesson learned by radicals and modernists of all stripes since.

Absent the fertilizer of a Protestant tradition or strong “enlightened” movements, liberalism faced tough odds in Spain. It was then in liberalism’s best interest not to present itself as revolutionary in nature, but rather as some sort of organic evolution of tradition (which is incidentally—and shockingly—how Jacques Maritain would see it too a century later). Ultimately, however, the strategy could only go so far, and liberalism did not triumph in Spain but through a sibylline combination of the persuasion and gradual adaptation embraced by the “moderate” and “conservative” liberals and the sheer force of the revolutionaries. Jaime Balmes, the great Thomist, described the dynamic well: “the ‘moderate’ party was destined to moderate the impulses of a revolution that was daring in its purposes and violent in its tactics; the ‘conservative’ party was destined to conserve the settled interests of a revolution now consummated and acknowledged.”

In 1814, once the French had been defeated and the King was free and safely back home, he took the advice of the “Persians”, made it clear that he would not sign or adopt the “Cádiz Constitution,” and attempted a return to the ancient institutions. Unrestrained now, the liberals replied by openly embracing revolution and attempting military coups and popular uprisings in 1814 (general Espoz y Mina), 1815 (commander Díaz Porlier), 1816 (the lawyer Vicente Richart), 1817 (general Lacy), 1819 (colonel Vidal), and 1820 (lieutenant colonel Riego), not to mention the secessionist and bloody civil wars launched in the Castilian Indies across the sea by liberals like Bolívar and San Martín. Unrest was to continue in decades to come.

In 1833, Ferdinand VII died without male issue. A strong case existed under Spanish law that the crown should go to his brother, the infante Carlos María Isidro, a known anti-liberal who insisted on his hereditary rights. But Ferdinand’s widow, the Italian born Queen María Cristina, (rightly) suspected of liberal sympathies, claimed the throne for Isabel, the infant daughter she had born to Ferdinand. Civil war now openly broke out in the Peninsula and would last seven years. In July 1834, the liberals abetted another revolt in Madrid, this time killing 73 friars, and in 1836 a further military uprising forced María Cristina to reinstate the “Cádiz Constitution” in exchange for the liberals’ full-fledged support in her military campaign for the throne. It took the liberals this and another three civil wars during the 19th century to establish themselves over, if not wipe out, their legitimist opponents. Of these, a remnant is still active in the Spanish-speaking world. They are known as Carlists, in honor of the by-passed heir to the throne, and coalesce around the rallying cry of Dios, Patria, Fueros, Rey—God, Fatherland, Fueros, and King, a veritable program for the return to the old constitution.

[1] The Spanish original of the Manifesto is available online here: https://es.wikisource.org/wiki/Manifiesto_de_los_Persas. The translations of the Manifesto in this article are the author’s.

[2] Manifesto, paras. 134-135.

[3] Id., para. 112.

[4] Id., para. 113.

[5] On Fr. Ferrer and his work, see Rafael de Arízaga, “Magín Ferrer and the Fundamental Law of the Spanish Monarchy,” Ius et Iustitium (January 26, 2021): https://iusetiustitium.com/magin-ferrer-and-the-fundamental-law-of-the-spanish-monarchy.

[6] Magín Ferrer, Leyes Fundamentales de la Monarquía Española Según Fueron Antiguamente y Según Conviene que Sean en la Época Actual, I, xii-xiv (1843). The original is in Spanish and the translation is from the author.