Kenneth Pennington observed that “Pax and Concordia [peace and concord] were concepts deeply embedded in the medieval imagination.” It is all the more striking, then, that today peace as such is largely absent from public discourse in the Anglosphere and the wider sphere of Western liberalism. (Hence we ought not be surprised that Pope Francis, not a liberal, does speak of it consistently). Even when the word “peace” appears in the public discourse of liberal states and their leaders, it is often in an instrumental sense; one might say, for example, “we must make peace with X in order better to prepare for or prosecute conflict with Y.”

This instrumental sense reflects a deeper impoverishment of the very concept of peace. Under liberal legal and political theory, peace is standardly conceived as the absence of (sectarian) violence, and violence is seen as in some sense the natural state of human societies, against which artificial barriers must be constructed; violence is always threatening to break out, and by the same token is always at hand to be deployed against enemies of the liberal order. Classical law, politics and theology, by contrast, had and have a far deeper conception of peace as tranquillitas ordinis, the tranquility of order, which is the natural and normal state of polities. To be sure, peace is not less than order in the minimal sense, physical safety and the absence of killing, but in the classical conception it is also far more. Thus Suetonius relates in his Life of Vespasian that after triumphing in the civil wars and entering Rome, Vespasian “made it his principal concern, during the whole of his government, first to restore order in the state, which had been almost ruined, and was in a tottering condition, and then to improve it.” The establishment of civil peace includes both phases, not merely the first. Just as every creature finds their proper place in the divine order, “the distribution which allots things equal and unequal, each to its own place,” so too in the civil sphere, the tranquility of order impounds justice, in the classical sense of giving to each their proper due.

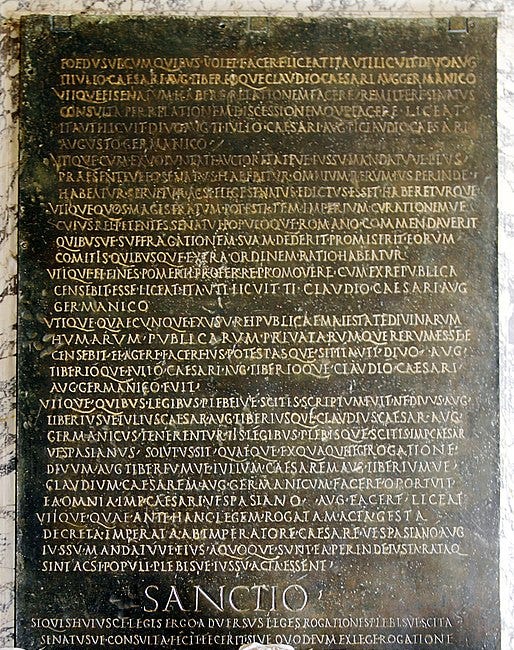

So too, in the classical conception, peace and justice are profoundly connected with law. As the Institutes of Justinian put it, in its very first phrases, “Imperial Majesty should not only be graced with arms but also armed with laws, so that good government may prevail in time of war and peace alike,” and so that the “wickedness” of “trouble-makers” may be driven out “through the paths of the law.” In general, as Ernest Kantorowicz observed, “[t]he function of all secular rule in the Middle Ages was defined in the recurrent formula Pax et Justitia [peace and justice]. If Justice reigned there was Peace; if Peace existed it was the sign that Justice reigned.” Peace and (legal) justice are “two sisters in close embrace.” This richer sense of peace and its connection to legality is widely embodied in classical law and legislation and their descendants; it is captured, for example, in the famous legal phrase “peace, order and good government,” a summary of the legitimate objects of legislation that appears in the British North America Act 1867 and in the fundamental laws of many other Commonwealth polities.

Since The New Digest began publishing in late August, peace in the fullest classical sense, and its connection to law, has already emerged as one of our major concerns. Collected below are a trio of entries on peace, arranged in reverse order of date of publication. In the first, Michael Foran reflects on the relationship of peace and justice to the rule of law. In the second, Conor Casey relates peace and justice to the working legal presumptions the classical law uses in the interpretation of legal instruments. In the third, I discuss the violence of faction under American liberal democracy circa 2023, and the resulting need for an impartial arbiter to guarantee peace (incidentally, a need discussed in an elegant and instructive little book by Christophe Buffin de Chosal, which I read too late to include in the original post).

(1) Michael Foran:

Justice, Peace, and The Rule of Law

The above, Allegory of Justice and Peace, is a magnificent painting by Corrado Giaquinto, leading exponent of the Roman Rococo in the first half of the eighteenth century. Evoking the imagery in Psalm 85 where “Mercy and truth are met together; righteousness and peace have kissed each other”, it speaks to an ancient vision of the dual ends of good gover…

(2) Conor Casey:

What Pleases the Prince is Peace and Justice

A deeply impressive legacy of the classical legal tradition was the capacity of its leading jurists to convincingly reconcile two competing imperatives of good government: how to both empower and constrain the State so that it is ordered to the common good

(3) My own entry:

America Needs A Podestà

America Needs a Podestà Mr. Madison told us, in perhaps his most famous work, that “among the numerous advantages promised by a well constructed Union, none deserves to be more accurately developed than its tendency to break and control the violence of faction.” In the spirit of Our Framers, let us accept Mr. Madison’s premise, noting only that it is an…

I close with Burgundy’s famous plea for peace between the monarchs of France and England, at the end of Henry V:

Let it not disgrace me

If I demand before this royal view

What rub or what impediment there is

Why that the naked, poor, and mangled peace,

Dear nurse of arts, plenties, and joyful births,

Should not in this best garden of the world,

Our fertile France, put up her lovely visage?

Alas, she hath from France too long been chased,

And all her husbandry doth lie on heaps,

Corrupting in its own fertility.

Her vine, the merry cheerer of the heart,

Unprunèd, dies. Her hedges, even-pleached,

Like prisoners wildly overgrown with hair,

Put forth disordered twigs. Her fallow leas

The darnel, hemlock, and rank fumitory

Doth root upon, while that the coulter rusts

That should deracinate such savagery.

The even mead, that erst brought sweetly forth

The freckled cowslip, burnet, and green clover,

Wanting the scythe, withal uncorrected, rank,

Conceives by idleness, and nothing teems

But hateful docks, rough thistles, kecksies, burrs,

Losing both beauty and utility.

And all our vineyards, fallows, meads, and hedges,

Defective in their natures, grow to wildness.

Even so our houses and ourselves and children

Have lost, or do not learn for want of time,

The sciences that should become our country,

But grow like savages, as soldiers will

That nothing do but meditate on blood,

To swearing and stern looks, diffused attire,

And everything that seems unnatural.

Which to reduce into our former favor

You are assembled, and my speech entreats

That I may know the let why gentle peace

Should not expel these inconveniences

And bless us with her former qualities.