America Needs a Podestà

Mr. Madison told us, in perhaps his most famous work, that “among the numerous advantages promised by a well constructed Union, none deserves to be more accurately developed than its tendency to break and control the violence of faction.” In the spirit of Our Framers, let us accept Mr. Madison’s premise, noting only that it is an entirely separate question exactly how well constructed our constitutional framework is in that regard. In the United States circa 2023, one may be forgiven for wondering, heretically, whether the faction-controlling mechanisms identified by the Father of the Constitution are working quite as well as he hoped. (Endlessly fascinating is the double-consciousness of the many American legal conservatives who believe both that the United States has sunk into a nightmare of factional tyranny, and also that our Constitution, expressly designed to prevent this very state of affairs, is the best in the world). Mr. Madison put his hopes in the refining and enlarging of public views through the electoral system (here one can only weep), in the system of checks and balances, and in the vast size of the American republic. But all of these just as plausibly exacerbate rather than reducing conflicts of impassioned public opinion and factional strife, as Lord Bryce observed in 1888. It seems that the transformation of the American republic into a continent-spanning de facto empire, with a population that is highly heterogenous on geographic, cultural, and other dimensions, has undermined many of the assumptions on which Mr. Madison relied.

Happily, the Madisonian mechanisms are not the only method to break and control the violence of faction. I offer here a modest proposal for curing the ills of faction in our current, distinctly nonideal circumstances. The proposal may sound novel, even alarming, but the seemingly novel is often just something that has been forgotten, and the theme of the New Digest is, after all, to adapt and translate classical principles and ideas to our brave new world. Non nova, sed nove.

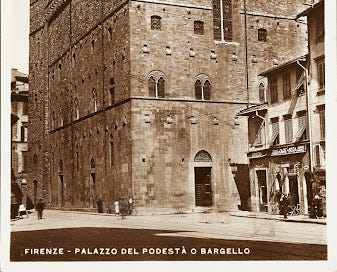

My suggestion, then, is that the United States should appoint a podestà. As we all know, given the fine historical education now offered in schools across the land, the office of the podestà was developed by the Italian communes of the mid-12th century and beyond as a cure for the ills of internal factionalism. The most striking and characteristic feature of the institution was that the podestà was typically an outsider, a citizen of another commune or city-state. That feature was a response to the evils of domestic conflict, and to the inadequacy of the alternatives.

What to do when no domestic faction trust the other(s) to govern, to judge impartially, or even to administer the machinery for selecting those who govern or judge? The problems with the separation of powers under these conditions are that, first, the separation of powers is not the same as the separation of parties or factions (one faction may dominate all branches simultaneously); second, that the domination of one branch by one faction, and another by another, and so on, may simply multiply rather than prevent or reduce injustice (especially insofar as each branch possesses some power of unilateral action — consider the exercise of selective prosecutorial discretion for factional ends); and third, that even if factions are distributed across branches so as to possess a mutual power of effective veto, the only result may be gridlock and stasis that tends to make the law obsolete and dysfunctional. In the extreme — and this is surely an absurd and science-fictional concern — the Nation might end up, say, trying to address changing problems of the environment, labor and immigration under statutes whose basic frameworks were created half a century ago or more.

The Italian communes then, with unimpeachable logic, turned to outsiders — foreigners if you like — from other city-states, who would be at least somewhat removed from the bitter logic of domestic strife and stand above the warring factions. The most famous description was written by Leander Albertus to describe the inauguration of the office of podestà in Bologna around 1151-3:

The citizens, seeing that there often arose among them quarrels and altercations, whether from favoritism or friendship, from envy or hatred that one had against another, by which their republic suffered great harm, loss and detriment; therefore, they decided, after much deliberation, to provide against these disorders. And thus they began to create a prudent man of foreign birth their chief magistrate, giving him every power, authority, and jurisdiction over the city, as well over criminal as over civil causes, and in times of war as well as in times of peace, calling him praetor, as being above the others, or podestà, as having every authority and power over the city.

The institution spread and developed, spurred on in part by the appointment of podestà in imperial cities by Frederick Barbarossa, and then because the Italian communes found it a useful innovation. Although details varied across communes and over time, in standard cases the podestà was a member of the nobility or otherwise eminent; was appointed or elected by the city magistrates for half a year, a year, a term of years, or in some cases even for life; took an oath to respect and enforce the laws; had to account for his public acts at the end of his term; and, perhaps most importantly, combined in one set of hands all powers of governance and judgment. Imagine the combination of rulemaking, enforcement, and adjudicative functions currently possessed piecemeal by the Federal Trade Commission, the Federal Communication Commission, the Department of Justice, and so forth and so on, all collected and entrusted to one man.

My modest proposal, then, is that Americans now loathe each other so much that only a foreigner can govern us with right and justice and, crucially, the appearance of justice — justice that is widely perceived to be such. I flatter myself that this proposal will immediately attract bipartisan and cross-factional support (surely?). After all, on the one hand, the Party of Order should find it very appealing that the podestà will have the imperium and potestas, the authority and power, to rule with a firm hand, overriding for example the selective prosecutorial discretion that, in the view of many American conservatives, has delivered us into the grip of “anarcho-tyranny.” (And to the extent that the Party of Order overlaps in part with the Grand Old Party, adherents of the latter might want to reflect that their chances of ever winning another presidential election may well be slight. Why not try to change the rules of the game?) On the other hand, the Party of Liberty generally favors, at present anyway, expansive administrative authority and the updating of the law. That Party has recently been much in favor of independent agencies, and in a sense the podestà is the ultimate independent agency. Furthermore, under this proposal, I can truthfully assert, no American will be above the law.

Who then ought our podestà to be? It should be a foreign figure of undoubted probity, experienced in public affairs, governance and diplomacy, with no direct interests flowing from the governance or adjudicative decisions of the United States, and at least partly removed in a broader cultural sense from our internal Cold War. A number of figures might fit these criteria. I have my own candidate; others are of course possible. In the Italian communes, I should add, great efforts were made to ensure that the podestà remained legally and even physically distant from the ordinary structures of governance, to the extent of being “confined in a luxury palace to keep them from being influenced by any of the local families.” Perhaps we might even create such a venue, right on the Potomac.

There are, of course, a thousand possible objections to such a scheme. There may for example be just a few legal details to be ironed out, involving the relationship between the President and the podestà, and the rather obscure constitutional limits on delegation of statutory authority to foreign actors. And one must confess that, on occasion, the podestà might slip off the bonds of the law altogether. But the latter concern is an argument for making those bonds looser, not tighter. And more generally, under our nonideal conditions, the uncertain evil one doesn’t know may be preferable to the certain evil one does know. The former may at least have a higher variance, some possibility of working out well. Is the status quo any better, or our current trajectory? And as for the legal issues, our constitutional law has at times accommodated equally strange institutional novelties. At a minimum, I suggest, the concept of an American podestà should abandon its defensive crouch.

[Note to the literal-minded, the humorless, and Wikipedia: as with certain other modest proposals, the foregoing should provide rich ammunition for friend-enemy politics masquerading, albeit rather poorly, as serious commentary or even “scholarship”].

So nice an inaugural piece. I read all the hyperlinks prior to this brief comment. Look forward to another forward step in the direction of a brave new world. Permit me to leave 3 quotes: "The rarer action is in virtue than in vengeance" - Prospero; and "As iron sharpens iron, so a friend sharpens a friend” ... "The fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom" - a King called Solomon.