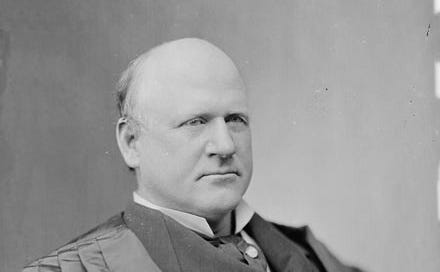

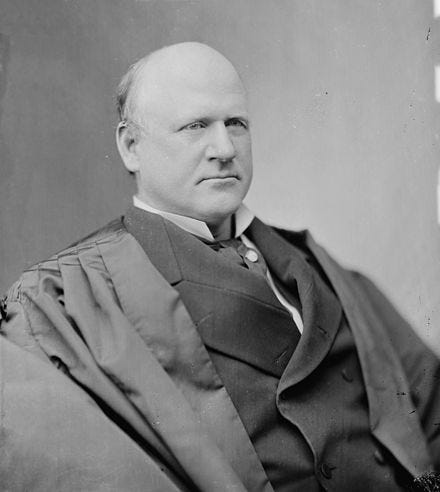

Justice John Marshall Harlan (1833-1911)

The New Digest is pleased to present this post from William G. Benson. Mr. Benson is an undergraduate student at The Catholic University of America pursuing a degree in politics with a concentration in political theory. William is the co-founder and editor-in-chief of The American Postliberal, a magazine of Catholic Political Realism. He has been published in The Wall Street Journal, The Federalist, The American Mind, The American Spectator, The Daily Caller, and Crisis Magazine.

“While this court has not attempted to mark the precise boundaries of what is called the police power of the State, the existence of the power has been uniformly recognized, both by the Federal and state courts. This power extends at least to the protection of the lives, the health, and the safety of the public against the injurious exercise by any citizen of his own rights,” Justice Harlan wrote in his dissent in Lochner v. New York.1 Lochner was a judicial failure because it could not reconcile a positive vision of the common good with the will to expand the autonomy of the individual. Lochner is significant because it departs from the common good legal tradition by subverting the police powers of New York to care for the common good of the political community, neglects to recognize an overarching account of the common good in law, rejects precedent of the common good in American law, and fundamentally changes the relationship between man, law, politics, and the state. This ultimately sheds light on the evolving relationship that can be found between law and politics; that they can either work together or against each other in the context of the political system and the Supreme Court.

Before proceeding to Lochner, it is important to address the significance of the classical legal tradition and Harvard law professor Adrian Vermeule’s Common Good Constitutionalism,2 along with its role in American law. According to Vermeule, the classical legal tradition begins with Roman law, canon law, and civil law. These forces, combined with Aquinas’ definition of law as “an ordinance of reason for the common good, made by him who has care of the community, and promulgated,” provide a guiding principle and justifications for instituting law. Vermuele takes this definition and seeks to revive through our conception of law today. The fundamental position of Common Good Constitutionalism is that our application of law and use of constitutional provisions can change as they are reflected in present circumstances, an argument with foundations in Aquinas and John Henry Newman. In American law, “the sentiment for this can be found in McCulloch v. Maryland (1819), where the Supreme Court ruled that ‘[the] Constitution [is] intended to endure for ages to come, and consequently to be adapted to the various crises of human affairs.’”3 Therefore, law must be read, constitutional provisions must be interpreted, and ultimately applied in light of the common good.

Finally, Vermeule posits that it is impossible to separate law from morality, and all law applies a moral vision to the political community. Thus, Vermeule specifies the aims of what law interpreted for the common good are:

“Common Good Constitutionalism takes as its starting point substantive moral principles that conduce to the common good, principles that officials (including, but by no means limited to, judges) should read into the majestic generalities and ambiguities of the written Constitution. These principles include respect for the authority of rule and of rulers; respect for the hierarchies needed for society to function; solidarity within and among families, social groups, and workers’ unions, trade associations, and professions; appropriate subsidiarity, or respect for the legitimate roles of public bodies and associations at all levels of government and society…”4

These objective aims are the fundamentals of Common Good Constitutionalism and interpreting law as a reflection of the common good. All of this serves to recognize that the state can actively seek the common good and that law is neither a permanent assertion of original meaning nor can be limited in an abstract way. Similarly, as evidenced with Lochner, any attempt to subvert this relationship of law to the common good as its core purpose is also an abuse of the law.

Lochner is significant because it rejects the proper scope of state police powers, damaging the common good, and revealing the conflict in the relationship between law and politics. Lochner centers around the relationship between a New York baker and his employer. The plaintiff, Joseph Lochner, owned a bakery in Utica, New York. Lochner required his employees to work over sixty hours in one week, a violation of New York’s Bakeshop Act of 1895, which stipulated that a baker could work no more than ten hours a day or sixty hours per week. Lochner was charged in New York county court and convicted of a misdemeanor. He was sentenced to pay a fifty dollar fine.10 Lochner’s case eventually reached the Supreme Court, where the court asked whether the exercise of police powers by the state of New York was justified in regulating the freedom of the individual to enter into contract for his labor, pursuant to the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. In other words, they were considering the relationship between police powers and the liberty to contract. The Supreme Court ruled in favor of Lochner, invalidated the New York law, and stated that the baker was free to work as many hours as he pleased.

The Court reasoned that the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment protects an individual’s freedom to contract, and thus New York’s labor law was an unconstitutional interference with such freedom. In particular, the decision represented a kind of legal formalism, where the court had to decide whether the liberty of contract was an area of personal liberty or police powers.5 In other words, unless the state has a legitimate reason (concerning the health, safety, and morals of its society) to interfere via their police powers, they cannot regulate areas of personal liberty. The majority believed New York did not meet this standard to interfere, as there were no justified concerns in regards to health and safety to warrant government interference in the professor of bakers. Since there were no legitimate considerations to uphold New York’s law, particularly as it sought to interfere with the right of an individual and an employer to contract labor, both parties had the right to purchase or sell their labor in this instance. In essence, the court stated that bakers “are in no sense wards of the state,” and are just as capable as any other to make their own decisions regarding their labor.

The reasoning of the Court is precisely where Lochner gains its significance; it rejects fundamental premises of concrete recognition of the common good. Police powers, rightly understood, allow the state to pass laws for the “health, safety or morals” (the common good) of their polity. The majority opinion is not wrong when it believes that there may be clear limits to these powers, but is wrong when it claims that the situation of Lochner does not apply to this standard, and the health of the laborer is not as important as his “liberty of contract.” To reject the use of police powers in this situation, where the state of New York clearly had an interest in protecting bakers, is to attack the use of police powers entirely. Primarily, it places conceptions of “liberty” over the common good and the application of law. If New York cannot protect its citizens from overwork and exploitation, the state cannot fundamentally govern. If the state cannot fully govern, then all of its interests are under attack. Therefore, Lochner is not only wrong in the case of the baker, but the implications for its reasoning extend far beyond the specific case. What else is considered to be “personal liberty” that the state is not allowed to interfere with? As such, Lochner is significant because it rejects the scope of police powers, believing there are areas off limits to the common good, and damages the definition of law as a reflection and interpretation of the common good. This sentiment is best recognized by Justice Harlan, who in his dissenting opinion in Lochner wrote:

“Granting then that there is a liberty of contract which cannot be violated even under the sanction of direct legislative enactment, but assuming, as according to settled law we may assume, that such liberty of contract is subject to such regulations as the State may reasonably prescribe for the common good and the well-being of society, what are the conditions under which the judiciary may declare such regulations to be in excess of legislative authority and void? Upon this point there is no room for dispute, for, the rule is universal that a legislative enactment, federal or state, is never to be disregarded or held invalid unless it be, beyond question, plainly and palpably in excess of legislative power.”6

Justice Harlan recognizes that liberty of contract, and thus all political rights, are subject to the common good and prescriptions of the state. It is not that there are no limits to police powers; rather, it should be presumed that the legislature is acting competently and rationally within its powers to secure the common good of its citizens. As Harlan contends, a law can only be disregarded if it is absolutely certain it is an abuse or overextension of legislative power. The freedom to contract is what has limits upon it, especially as matters of health and dignity are concerned. Harlan’s argument gets to the heart of Lochner’s significance: this case broadly rejects the claims the state has the power to promote the common good. As far as Vermeule’s Common Good Constitutionalism is concerned, Lochner also rejects the need to protect the dignity of professions, and casts aside an instance where law clearly needs to be read and applied to the common good. This, too, is important because it recognizes that Lochner misconceives the relationship between law and politics. Law should be seen as a standard, influenced by the natural law and the principles of the common good that flow from it. Politics, similarly, should be understood as the determinations of how law is to be written and applied, and more specifically, the values that are written into the law.

In the case of Lochner, both through Harlan and Vermeule, the standard is clear: New York had the power and duty to regulate the profession of bakers for the common good. However, the political process subverted this duty. It is fashionable here to say that Lochner was an instance of “judicial activism,” and the Court’s majority applied its politics, or own personal preferences, to reach a desired result in Lochner. This is substantively true, but not the heart of the issue. Recognizing that all politics is ultimately a reflection of morality, it is not right to say politics in the abstract was the issue. Rather, it was the majority’s application of the wrong politics. The distinction here is subtle, but nonetheless important. The majority, by applying its own conceptions of liberty and desire to limit the power of the state, applied a wrong conception of politics and political morality, instead of the right one: interpreting New York’s law in light of the common good and allowing the state to properly regulate labor for the health and safety of bakers. Law as a standard is subverted by the whims of a political institution, the Court, seeking its own ends rather than the common good. This makes Lochner all the more significant because of its stark break with the demands of viewing law as an extension of the common good. This shows that the relationship between law and politics is not always smooth, but can be contentious as the law demands one thing and the human will another.

In a review of Vermeule’s theory, Professors Jeffery A. Pojanowski and Kevin C. Walsh argue that Vermeule reads Harlan’s dissent incorrectly, saying Harlan relies more on the positive law that is the Fourteenth Amendment, rather than an abstract appeal to the common good.7 They contend that Harlan’s argument for the common good and the ability of the state to act is rooted in the Fourteenth Amendment, rather than an overarching common good to be applied in all forms of law. This is significant because it exemplifies the way in which Lochner is interpreted and affects how the common good is reflected in law. Ultimately, the matter comes down to first principles — the question of where the text ultimately receives its meaning.

By creating a broad distinction between a more abstract appeal to the common good, derived through the natural law, and the Fourteenth Amendment’s “enactment” of the common good, Pojanowski and Walsh create a de facto claim that the written text matters more than how the natural law permeates the text—the essential originalist argument. While it is indeed good that the authors accept Harlan’s conclusions, it is a mistake to say that the text matters more.27 Rather, as all law is understood, it is informed by and derived from the natural law. By creating this distinction, Pojanowski and Walsh do great damage to the classical legal tradition. If law is to only be understood in terms of this distinction, an artificial limit on the ability of the state to provide for the common good is placed. What happens when the “original meaning” prevents the common good from being enacted? This posits that the state can be limited in its ability to provide for the common good.

In extending their conclusions, the implication that abstract limits to state power are more important than using justly wielded political power for the common good does damage not only to the ability of the state to act as a political force, but to our fundamental understanding of law’s primary ordering. If the 14th Amendment is what grants Harlan’s reading legitimacy, then there really can be no common good expressed in law except when embodied in the original meaning of the Amendment. A law gaining its legitimacy insofar as it is written for the common good is not the same as being interpreted for the common good. This interpretation of Lochner creates a conflict between law and politics. On the classical view, law can be seen as the overall reflection of the common good, whether intentionally placed in the law or through interpretative presumptions that harmonize the law with the common good where possible. On Pojanowski and Walsh’s argument, by contrast, politics, or the actual writing and original meaning of the law, comes into conflict with the framework of law if the text is granted primacy over the inherent need for the common good.

Finally, Lochner is significant because it rejects precedent of the common good in the American tradition. It is thus necessary to point out that courts have long recognized the role of the common good in law and public life. Specifically, Vermeule highlights an important case to emphasize this point. In Mugler v. Kansas (1887), the Supreme Court, in a decision written by Justice Harlan, upheld as constitutional state regulations that set parameters for the manufacture or sale of alcohol. In other words, the Supreme Court has in fact recognized the power of the state to regulate health, safety and morals for the sake of the common good.

While this may seem like a niche expression of the common good found in a minor case in American jurisprudence, the fact that it is “minor” is precisely the point. It subtly and implicitly recognizes the common good, and without second thought, condones the authority of the state to protect the health, safety, or morals of its citizens. These cases show conformity between law and politics’ relationship, whereby the political institutions, regardless of what they may or may not want, submit to the authority of law and the common good. Admittedly, this is not to say that the common good is not a contentious point in American politics or that there is no debate over what the common good may be in a particular situation; rather, there has been consistent support for the common good in American law. All of these cases in some way exemplify the state acting for the common good. Lochner is what is out of place, not the common good.

Justice Holmes states in his dissent that Lochner bases its decision off of laissez faire (or free-market absolutest) economic theories, “which a large part of the country does not entertain.” Holmes acknowledges that “a constitution is not intended to embody a particular economic theory.” While there is much to disagree with in Holmes’ jurisprudence, he is right that the Constitution is not about one economic theory. To extend his reasoning, it is about the common good and how it informs a vision of an economic system. Thus, Lochner’s departure from this tradition is startling, particularly because this same logic throughout public life has led many to believe that the Constitution is merely meant to protect individual rights and economic activity rather than establish a governing structure that can robustly promote the common good. This too affects the relationship between law and politics, especially because law serves not only as a standard, but as a history and tradition as well. In Lochner, law is violated in the pursuit of a political vision that does not come in accordance with it.

The emphasis on tradition is what matters here, particularly because of the importance of custom in informing law. “Aquinas argues that frequent changes in law are harmful to the common good because law must become custom in order to gain legitimacy … Custom acquires the force of law by reason of it existing for a long period of time during which habits are given chance to develop. Custom’s power is greater than law.”8 Hence when the ideology found in the majority’s opinion in Lochner suddenly supplants the common good, not only is custom disrupted, but the view of the purpose of law itself is distorted. The common good is replaced by individual autonomy. This is not only a threat to custom, that being a healthy work culture with just limits placed upon it, but also a revelation as to how the decision in Lochner had no sense of law insofar as it violated basic customs and expectations of a culture of the common good.

Lastly, the whole relationship between law and politics must be addressed, and specific conclusions must be drawn about what influenced the majority’s decision. Lochner shows the tension by which law and politics can be at odds, namely that the law and the common good can be at odds with one's politics, as in the case of the majority. Lochner is significant because it continues the “progress” and emphasis on the “choosing power”9 of the Enlightenment ideology of liberalism. It places a higher emphasis on individual autonomy rather than the force law. It changes the nature of what is seen as the political good of the laborer and community. This damages the common good and the classical framework of law. Ultimately, a common good interpretation of law must reconcile politics to law.

To highlight these concrete applications, a focus on liberalism broadly is necessary. The goal of liberalism is “freedom,” but not in the way it was traditionally understood. Ancient and classical freedom, doing “what one ought,” was subverted by liberalism’s belief in “what one wants,” or the complete autonomy of the individual and a freedom ultimately unaccountable to human or natural law. This disordered conception of freedom is precisely what makes Lochner significant; it is a case so evidently connected to liberalism. Lochner’s placing of the individual liberty to contract above the wellbeing of the baker represents placing the lower freedom over the higher freedom. Liberalism, with its focus on “progress,” would cast this aside for the accumulation of capital and production, the common good be damned.

This calculation shows that the relationship between law and politics affects everything we do. There is no neutral court decision because they all affect public life. Law and politics can work together or they can fight each other for dominance. Either the law and the common good will rule, or personal, political whims will. The Court, as seen in Lochner, has a large role in determining this. Through the Court’s actions in Lochner, law and politics destroy one another as the law seeks the common good, but the politics of liberalism in Lochner attempts to destroy it. Some may claim that ultimately this argument is a broad generalization, and especially irrelevant since the majority still recognizes the police power. However, the issue is not exactly what the majority intended or did not intend; rather, the concern is that they chipped away at the core basis of law. Therefore, for law and politics to be truly reconciled and their relationship to flourish, politics must be reconciled and interpreted under the common good standard of law, meaning the logic of Lochner must be abandoned.

In conclusion, as Vermeule writes, “sooner or later, on this view, law’s real nature will reassert its claims.”10 Lochner failed because it departed from the common good by subverting police powers, rejecting American law’s common good precedent, and redefining how law is viewed in terms of man and the state. All of these factors ultimately flow from the relationship between law and politics. In the case of Lochner, their conflict and relationship can be contentious, but ultimately can be reconciled under a proper view of the common good, as outlined in Vermeule’s Common Good Constitutionalism.

In the end, however, “no amount of fundraising by the Federalist Society can get well-read law students and young legal academics to unsee that the founders were nothing like Robert Bork. They were in fact classical lawyers and natural lawyers”11 with the common good in mind. Therefore, Lochner v. New York amounted to betrayal: betrayal of a rightly ordered polity instituted for the common good. This fundamental rejection of the basic grounds for workplace protections –– a limit on the number of working hours –– has done grave damage to not only how America perceives liberty, but especially how it perceives law and the common good itself.

198 U.S. 45, 65 (Justice Harlan, dissenting).

Vermeule, Adrian. Common Good Constitutionalism: Recovering the Classical Legal Tradition. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2022.

Benson, William G. “Essay: Common Good Environmentalism.” The Desk of William G. Benson, January 18, 2022. https://wgbenson.substack.com/p/essay-common-good-environmentalism;

Vermeule, Adrian. “Beyond Originalism.” The Atlantic. Atlantic Media Company, March 31, 2020. https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/03/common-good-constitutionalism/609037.

Shaman, Jeffrey M. “On the 100th Anniversary of Lochner v. New York.” Tennessee Law Review 72 (2005), 17, 19.

198 U.S. 45, 68 (Justice Harlan, dissenting)

Pojanowski, Jeffrey A., and Kevin C. Walsh. “Recovering Classical Legal Constitutionalism: A Critique of Professor Vermeule’s New Theory.” Notre Dame Law Review, November 7, 2022, 433.

Talamas, Tatyana. “The Power of Human Custom and Its Relationship to the Kinds of Law According to Thomas Aquinas.” Academia.edu, 6.

Pecknold, Chad. “Errors of Will.” Postliberal Order, September 26, 2022. https://postliberalorder.substack.com/p/errors

Vermeule, Common Good Constitutionalism, 184.

Vermeule, Common Good Constitutionalism, 184.

Excellent text and analysis! As a great Brazilian writer once said, 'all politics that is not tradition is certainly treason.' The same applies to law, which, as rightly noted, is closely connected to politics. In a sense, all the Americas share the ius commune tradition, each in its own way. Unfortunately, to varying extents, this tradition has increasingly been abandoned in favor of liberal and progressive treason. That’s why works like this, which aim to recover the classical roots of law, are so important—not out of mere historical curiosity or originalist attachment, but because they represent the true form of law that should be lived and applied. May God grant these initiatives success.

Are you kidding me? Have you seen the bakers? They need 70+ hours per week to work off those extra layers of belly fat.