Aulus Gellius on Factionalism

Is the cure for civil conflict to force everyone to take sides?

While I’m thinking about factionalism, its causes and cures (and putting aside the Madisonian mechanisms in Federalist 10 and elsewhere, whose success can perhaps best be judged by a glance at American politics 2023):

Below is a passage in italics from Aulus Gellius’ Noctes Atticae II.12 (translated by John Carew Rolfe for the Loeb series). The passage presents a curious hybrid mechanism, part mandatory law, part invisible-hand process, which aims to curb the violence of faction by forcing the good and wise, who would otherwise remain above the fray, to take sides. After the passage, I pose a few largely skeptical questions about the mechanism. (I’m not sure who those questions are best addressed to. Perhaps Solon, whose law is [supposedly] at issue. Aulus Gellius seems to approve of the idea behind the law, but perhaps he is just doing what he does best, which is to present an amuse-tête with a point).

§ 2.12 A law of Solon, the result of careful thought and consideration, which at first sight seems unfair and unjust, but on close examination is found to be altogether helpful and salutary:

Among those very early laws of Solon which were inscribed upon wooden tablets at Athens, and which, promulgated by him, the Athenians ratified by penalties and oaths, to ensure their permanence, Aristotle says that there was one to this effect: "If because of strife and disagreement civil dissension shall ensue and a division of the people into two parties, and if for that reason each side, led by their angry feelings, shall take up arms and fight, then if anyone at that time, and in such a condition of civil discord, shall not ally himself with one or the other faction, but by himself and apart shall hold aloof from the common calamity of the State, let him be deprived of his home, his country, and all his property, and be an exile and an outlaw." When I read this law of Solon, who was a man of extraordinary wisdom, I was at first filled with something like great amazement, and I asked myself why it was that those who had held themselves aloof from dissension and civil strife were thought to be deserving of punishment. Then those who had profoundly and thoroughly studied the purpose and meaning of the law declared that it was designed, not to increase, but to terminate, dissension. And that is exactly so. For if all good men, who have been unequal to checking the dissension at the outset, do not abandon the aroused and frenzied people, but divide and ally themselves with one or the other faction, then the result will be, that when they have become members of the two opposing parties, and, being men of more than ordinary influence, have begun to guide and direct those parties, harmony can best be restored and established through the efforts of such men, controlling and soothing as they will the members of their respective factions, and desiring to reconcile rather than destroy their opponents. The philosopher Favorinus thought that this same course ought to be adopted also with brothers, or with friends, who are at odds; that is, that those who are neutral and kindly disposed towards both parties, if they have had little influence in bringing about a reconciliation because they have not made their friendly feelings evident, should then take sides, some one and some the other, and through this manifestation of devotion pave the way for restoring harmony. "But as it is," said he, "most of the friends of both parties make a merit of abandoning the two disputants, leaving them to the tender mercies of ill-disposed or greedy advisers, who, animated by hatred or by avarice, add fuel to their strife and inflame their passions."

The idea here doesn’t seem to be that factionalism has to get worse before it gets better, in the sense that only increasing the bitterness and costs of civil conflict to all concerned will bring everyone to their senses. That idea would at least be internally consistent, although it seems to me wildly imprudent. There is no reason that polities cannot devolve into an essentially indefinite series of factional tit-for-tat measures that make all concerned permanently worse off; history is full of examples, and there is no invisible hand supervising the process to make sure that it all comes right in the end.

Rather the idea in the passage seems to be that the good and wise should genuinely take sides, establish a kind of partisan credibility by manifesting their commitment to one faction or another, and then use that credibility to moderate, soothe and reconcile the passions of the contending parties. But it does not seem internally consistent to command the good and wise to manifest factional “devotion,” in the sense of passionate commitment to friend-enemy politics, and then to hope that at some later stage they will turn around and exercise a higher wisdom aimed at moderating faction in the name of the common good. The psychological and political state of enmity needed to generate credibility at the first stage all but guarantees that the later stage of higher wisdom and moderating influence will never come to pass. One is reminded of the common phenomenon in which a lawyer assigned to argue for one side or another in a hard case comes to believe that the case is actually an easy one, and that the side for which the lawyer is arguing is indisputably correct. Alternatively, there is that stock literary character, the undercover policeman engaged in a mission of infiltration of a criminal gang, who must signal commitment to a gang by killing its enemies. The policeman almost invariably loses sight of his original aims in the process, or so the novelists tell us. I have no idea whether this is invariably true, of course, but it is surely a standing risk.

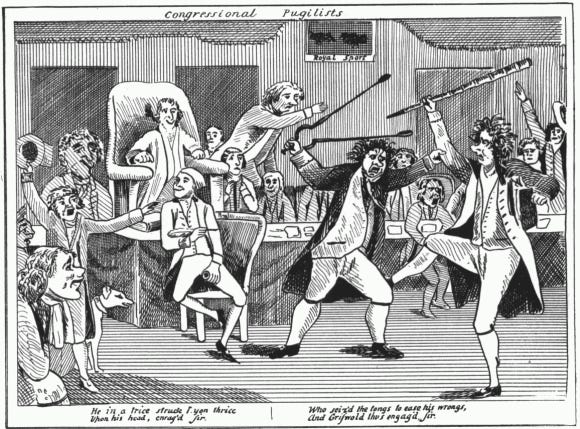

In short, I am skeptical that there are any plausible indirect invisible-hand-ish mechanisms that can make factionalism better by making it universal. Factionalism is inherently chaotic, a spreading distemper in the state that is born of competition for authority and that brings all sorts of disorder in its wake, including the perversion of the law and eventually violence. The necessary remedy is a restoration of political order, rather than clever fixes of the Solonian sort, however appealingly paradoxical the latter may be (and intellectuals are especially prone to fall for appealing paradoxes). Once the disease has taken hold in the polity, only strong medicine, direct political measures to abate the fever and to clarify the locus of authority in the state, can cure the patient — assuming of course that the patient survives the process of administering the cure.

I am not sure of the statistics around contemporary police infiltration, but as a historian there are certainly plenty of examples of double agents and false informers and agents provocateurs causing crimes from the "golden age" of anarchism and revolutionary politics in late 19th/early 20th century Europe. I am reminded in particular of the famous case of Yevno Azef, a Russian revolutionary and secret police agent who managed to use his unique role to profit from and advance his career in both institutions, having his police superior assassinated while getting his revolutionary superior arrested and gaining power and making money in both without ever making it particularly clear to which side (if any) his deepest loyalties lay.

It seems much more likely from history and human nature alike that people who "know better" (and therefore have no even delusional belief that these factional politics are benefiting the common good) forced to take part in factional politics they despise would learn to cynically use these factions for their own individual private interest than that they would be able to find hitherto-unknown ways to bend these factions to the genuine common good.

Samuel Moyn makes a similar argument to Aristotle about the liberal attempt to ‘humanize war’ to avoid atrocities. He argues that its effect has been to normalize and justify war rather than humanize it. He argues that the atrocities of war should not be denied in order to limit war. See Moyn, Humane: How the United States Abandoned Peace and Re-Invented War. I understand the criticism of supposed ‘humane war’ but not sure that ‘inhumane war’ is the right response. Common good just war criteria much more effective in limiting war than using executive will to make war ‘humane.’ Moyn does not even consider just war an option with his own liberal convictions, if I recall correctly.