Alexander Hamilton, Classical Lawyer

Recently, a post on X featured a quote from former Attorney General Ed Meese III, in which Meese characterizes the views of Alexander Hamilton in Federalist No. 78 on the power of the Article III judiciary. According to Meese, “As Alexander Hamilton said in The Federalist Papers, law is about the exercise of judgment and not will. Judicial activism is best understood as substituting judicial opinion for the command of law. The law is not an infinitely malleable tool.”

Now, I don’t think any classically minded lawyer believes or has argued that the law is “infinitely malleable,” although certain critics of common good constitutionalism frequently set up such a straw man in trying to advance textualism and originalism. The Framers are often quoted (selectively) to make it seem as though what Meese and others were arguing for is simply a return to Founding-Era practices that were widely believed then washed away in the 1960s. I wanted to briefly invite readers to consider since the 1980s, a certain Society’s presentation of the Framers might be distorted in support of a particular theory of interpretation.

Alexander Hamilton was among others things, like many of the Framers, a practicing lawyer, living and breathing in the received legal tradition of early America. One of the most famous cases Hamilton argued and won was Rutgers v. Waddington, decided in 1784 in New York state court. The specific issue in the case involved a putative conflict between a New York statute called the Trespass Act and the Treaty of Paris. The Act gave supporters of the Revolution the right to sue those who had occupied property that the supporter had abandoned to the British during the War of Independence. Elizabeth Rutgers had owned a large brewery and alehouse that she was required to abandon, and she later sued Joshua Waddington who had since taken it over. Hamilton represented Waddington.

Under the remarkable historical editorship of Julius Goebel, Jr., at Columbia Law School in 1964, Columbia University Press published a two volume series (highly recommended) called The Law Practice of Alexander Hamilton: Documents and Commentary. This work contains the five or so briefs Hamilton prepared for the case,1 as well as one version of the reported decision. Central issues in the case included: (a) whether the New York legislature could validly enact a law that violated the law of nations; and (b) could the Act be construed to be consistent with the law of nations and thus in favor of Hamilton’s client? Here are some interesting points of law Hamilton wrote in his argument. I present them for consideration the next time someone tells you he must have been a textualist and originalist, and that we ought to understand Federalist No. 78 in such a way:2

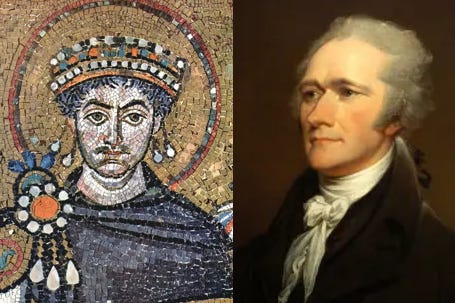

As one would expect, Hamilton cites numerous standard common law sources like Blackstone and Coke, the Law Reports, etc. But he just as easily relies, repeatedly, on Cicero, Justinian’s Institutes, Grotius, Vattel, Puffendorf, and other classical sources. The writings of these famous jurists represent valid legal principles for Hamilton just as much as decisions from the Law Reports or the statutes at issue.

His briefs were full of classical legal maxims that sit uncomfortably alongside modern textualist ideas, such as:

“A New case must be determined by the law of Nature and the public good. Ubi lex tacet Judex loquitur ! ! !” (exclamation marks by Hamilton)

When the provisions of a statute “are general … construction may be made against the letter of the Statute to render it agreeable to natural justice.”

“Many things within the letter of a statute are not within its equity and vice versa.”

“No statute shall be construed so as to be Inconvenient or against reason.”

“A statute against Law and reason especially if a private statute is void.”

“IN LAW as in Religion THE LETTER KILLS THE SPIRIT MAKES ALIVE.”

“The natural law of nations is universally binding on the conscience of nations.”

“[T]he jus gentium” (i.e., the law of nations) is part of the “great heads” of the “common law.”

Hamilton argued, at some length, “We have seen that to make the Defendant liable would be—to Violate the laws of nations & forfeit our character as a civilized people—to violate a solemn Treaty of peace & revive the state of hostility[—]to infringe the Confederation of the United States AND lastly to endanger the peace of the Whole[.] The Question is can we suppose this to have been intended by the Legislature? The Answer plainly is ‘THE LAW cannot suppose it’—If it was intended the act is void.” He then went on to invoke a number of the canons above to argue that the Act could be construed to exclude his client’s situation and be consistent with the law of nations.

A good deal of Hamilton’s argument was successful, even if the decision of the court proved controversial. The court held that the substantial portion of Waddington’s occupancy was outside the statute, and only a small portion of it was within the statute. A great deal more could be said about the Waddington decision itself (indeed, entire books have been written about it and its importance), but without question the decision there is also thoroughly classical in tenor. It recites at some length the principles of the “Law of Nature” and its binding character on all men and all nations and endorses and reconciles maxims of interpretation that both eschew judicial overreach while recognizing the judicial power to construe statutes in accordance with longstanding principles of the law such as those Hamilton cited.

As the editors of The New Digest frequently emphasize, the legal cosmology of the Founding was so thoroughly different than that depicted in textualist and originalist theory that it sometimes seems beyond belief to assert that founding-era lawyers were just doing textualism and originalism. In any event, perhaps this brief aside about Hamilton the lawyer may make you think more deeply about just what he might have meant in Federalist No. 78 when he rightly said the legislature exercises “WILL” but the judiciary only “JUDGMENT.”

As the editors observe, it was uncommon at the time for briefs to necessarily be submitted in that court. The brief drafts are likely oral argument outlines (and as a practicing lawyer, it is hard to not see them that way, as they represent short pithy statements of law, argument, facts, precedents, etc., organized in ways across drafts geared toward easier memorization with various heads to guide the attorney’s argument, including anticipating particular objections and what answer should be given). It is not clear which if any of these drafts still existing ever made it to the court in Waddington, but they do give us a clear insight into how Hamilton the lawyer felt he could argue the case. Moreover, many of Hamilton’s exact arguments and classical references made it into the court’s opinion, suggesting that, indeed, Hamilton delivered something like the argument laid out in his briefs, with success, before the court. For the particular quotations cited in this post, see I Julius Goebel, Jr., The Law Practice of Alexander Hamilton: Documents and Commentary pp. 331-419 (1964). Many thanks to the Regent University Law Library for allowing me to check out this work from one of its Special Collections.

I suppose someone might assert that Waddington was before our Constitution was enacted and that Article III changed the nature and scope of the judicial power given to federal judges as compared to what was exercised before. I will not dwell on this only to say it beggars belief, in my view. Nothing in the history of debates over Article III suggested that the nature of the power being given to Article III judges, “the judicial power,” was something radically or even materially different than the nature of that power as it had been exhibited by jurists for many centuries before and with which the Framers were deeply familiar.

Yes! We are given an overly simplified (and in some big ways outright misleading) read on founding era legal thought. The were not Originalists. It was rich and diversified, and thats why somethings can be misleading, for example, take the case you reference, its a New York state court case, based within a New York statute, and with New York commercial interests in the background, and New York’s relationship to treaty obligations (which differed than some other states given the strength of the commercial and financial interests within the NY that had ties to London, Amsterdam specifically but international matters in-general, that that law even got passed, unless it was a head fake of some sort, speaks to how there were popular structures in the state (yes, it could of also been a scam on the part of some tied in players who maybe cashed out before reversal, but there were pop structs in NY then and there alot better than this incident to show that)), it can be, along with the other examples and snapshots of thought typically given, misleading about Founding era legal reasoning, in NY there was a relatively much stronger center of gravity for cosmopolitan harmonization and as such the court system overall was more receptive to treaty and law-of-nations arguments than some other places, in states with stronger lower case "d" democratic impulses (and maybe also stringer anti-Loyalist sentiment) and less exposure to international trade pressure it could be different, and it wasnt just a two way, either-or split, there were multiple dynamics at play. ( so international commerce/international-law cosmopolitanism impulse vs local lower case "d" democratic impulse) (thats an oversimplified in some ways to put it) (and also there were more splits than just those two things)

Textualism indeed!