While it may be true that the English Common Law is quite different from Roman and Civilian law, it would be a mistake to describe it as anything other than a local variant of the classical tradition to which all three are a part. Rather than replicating whole cloth the doctrines of Roman law, or adopting a similar approach to the legal profession, the common law can be said to share in the classical legal cosmology in which civil positive law gives specification to, and is interpreted in light of, general background principles of natural law and the law of nations, understood as enduring commitments of the legal order.

Very few first-order legal rules or doctrines within the common law derive from the Civilian tradition. Nevertheless, there was a shared framework of higher-order legal concepts, one which situated posited human law within an existing ecosystem of moral principle and political practice. This legal system is a variant, not a child. It is born of the same cultural, religious, and intellectual zeitgeist, even if it is not a direct offshoot of the Roman tradition in the way that civil law is. Only a few decades before the laws of Ethelbert, Justinian had set down the Corpus Juris Civilis. Roman law had reached its perfection when English law was just beginning to take embryonic form.

While traditional laws drawn from Germanic roots were passed down orally at this time, this was only viable for small kingdoms. Ethelbert was, however, an ambitious king. Bede lists him as one of the first to hold imperium over other Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, and he is referred to as brethwalda, ‘Britian-ruler’ in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. He was also the first English king to convert to Christianity after the arrival of Augustine in 597.

This brought with it important consequences for the laws of England. Augustine and his missionaries brought with them a legal tradition far more complex than that of the Anglo-Saxons. They represented the dual heritage of Latin Christianity, informed by both the textual history of Rome and the moral foundations of what would become the natural law tradition. This was a legal culture highly focused on the acts of lawmaking and code creation but which had a strong understanding of the relationship between human artifice and underlying moral law.

The result of this influence was the creation of Ethelbert’s own code, fashioned, according to Bede, iuxta exampla Romanorum – ‘after the examples of the Romans’. This did not mean that Ethelbert had transposed Roman legal doctrine. Rather he had emulated the Roman way of making legal codes, inspired by the requirements of being a good Christian king, with an important royal duty being the creation and enforcement of law for the common good.

Ethelbert’s is the earliest surviving law code in any of the Germanic countries. There were two important features that set it apart: its form and its content. In form, Ethelbert departed from his continental precursors and chose not to promulgate his code in the lingua franca and the traditional language of law, Latin. Instead, he used the language of his subjects: Old English. It is not immediately obvious why he chose to do this, but it is fitting that he did, given the importance that the English legal system has placed on shared custom and lay involvement, particularly in the form of juries. These have been defining features of the Common Law and are reflected in the content of Ethelbert’s code. He did not transpose Roman legal doctrine, nor did he craft an innovative new set of norms. Rather, his code drew upon the traditional customs of his people, eschewing general legislation and focusing on the immediate spiritual and temporal needs of the kingdom.

The preservation of law and order was a central duty of any king and the avoidance of blood feuds was of paramount importance if Ethelbert was to maintain stability within his realm. Without a general system of objective justice, one killing could easily lead to another in retaliation and that could result in the decimation of families and even communities. As such, the majority of Ethelbert’s code concerns bote, compensation paid in restitution for injuries, signifying an effort to shift towards what we could call a system of restorative justice.

There is some evidence to suggest that many parts of the code was based on an oral precursor, meaning that Ethelbert was putting in writing the ancient custom of his people. The involvement of royal authority was primarily to set a determinative interpretation of this custom rather than enforcement or administration. At the time, it was not the king but rather the victim or his family who enforced the code. Later in the seventh century, however, the demands of kingship resulted in greater royal involvement. As subsequent Anglo-Saxon kings enacted their own codes, it was clear that a working system of compensation was conducive to a well ordered society and a flourishing kingship.

As royal authority expanded, the administration of justice began to develop a distinction between those crimes which could be addressed by compensating the victim and those which could not be. This latter category - boteless - corresponded with serious crimes which broke the king’s peace and were thus public wrongs which offended against the Crown. The king was now instrumental in the provision of justice and gradually assumed the role of directly enforcing the law and maintaining peace.

Royal involvement in legal administration expanded in the reign of Alfred the Great, who aspired to match the legislative achievements of the great Christian lawgivers from Moses to Charlemagne, believing that “the peaks of legislation [matched] the peaks of royal aspiration”. In this he succeeded, producing the largest Anglo-Saxon law code and earning recognition in Angevin times as the founder of English law. Part of this likely involved the consolidation and harmonisation of vast swathes of regional laws into a body of generally applicable principles through his expanding kingdom. Similar to Ethelbert, Alfred promulgated his code in the vernacular, contributing to what would become a great English tradition. Alfred built upon the foundations laid down by Ethelbert and his successors built upon those laid down by him.

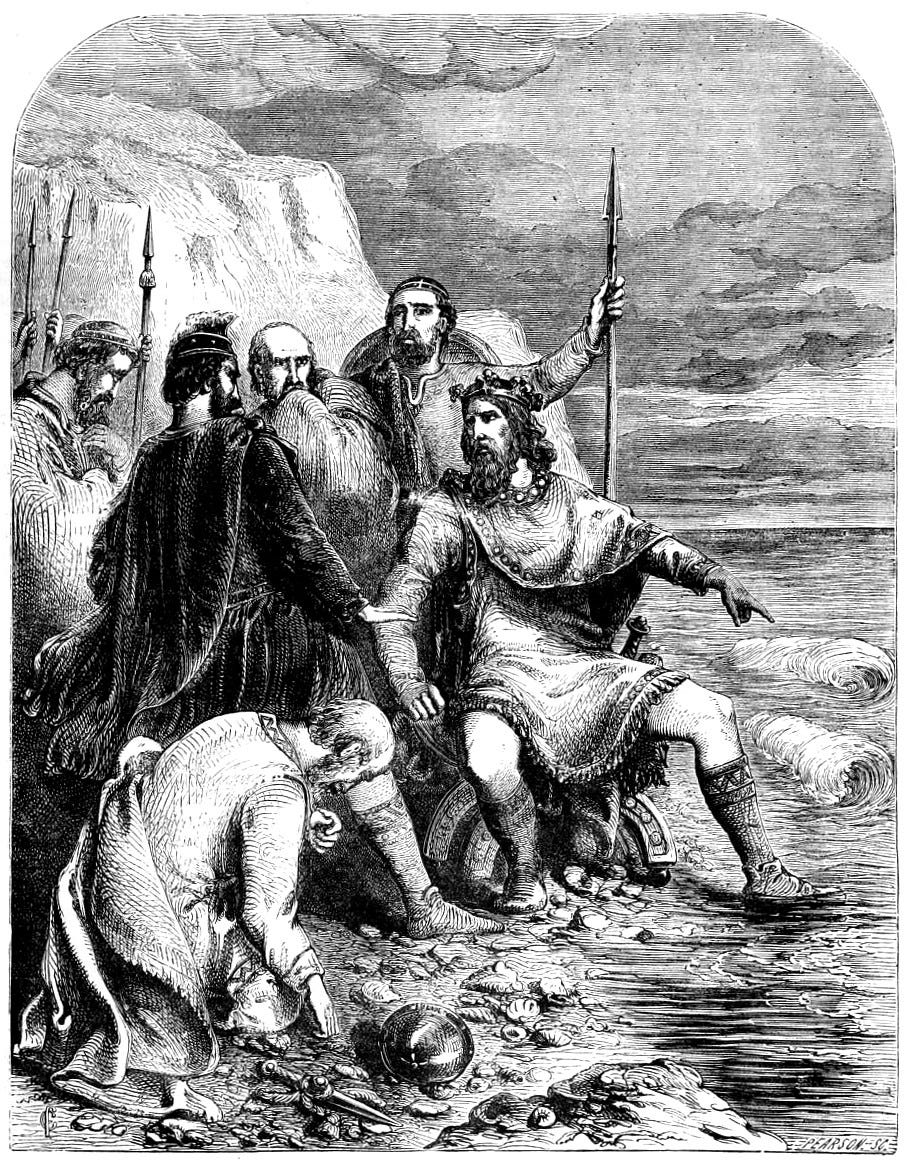

The last great lawgiver before the Normans was Canute, who was not Anglo-Saxon but Danish. He legislated to ensure the equal application of the law to his English and Danish subjects without discrimination, while recognising differences in custom when relevant. The legal code he issued in the early 1020s focused on continuity, building upon the foundations set down by his Anglo-Saxon forebearers. Canute was widely considered a wise and just king. Henry of Huntingdon recounts the often misinterpreted story of his encounter with the tides as an example of his “nobleness and greatness of mind”.

This was not a tale of a brutish king arrogantly commanding the tides. Rather, it was an example of a humble and wise king who, understanding the limits of temporal political authority, used this as a demonstration to “let all men know how empty and worthless is the power of kings, for there is none worthy of the name, but He whom heaven, earth, and sea obey by eternal laws”. Here we see Canute lauded as wise to see clearly the delicate interplay between the posited and the natural law. This reflects an ancient understanding of the relationship between law and morality upon which the common law is founded.

When the Normans arrived in 1066, they encountered a kingdom better administered than any in Europe, with fertile ground for the birth of a new legal system that would become the common law. William inhabited a role as King which was by this point intwined with the development and maintenance of law. The Norman conquest represented a seismic shift in governance, but it did not result in any lasting division between the laws of the conquerors and the conquered. For the most part, the Normans were content to accept important aspects of English culture and administration, preserving its laws in so doing. As a result, Anglo-Saxon infrastructure survived.

One change that William did make was to separate spiritual from temporal jurisdictions. The severing of secular law from ecclesiastical law would have wide reaching consequences for hundreds of years. Cannon law, the first law common to all of England, was now on a different trajectory to the secular law and solidified what would become the common law as a system of norms which is drawn from the customs and practices of the people. Canon law took as its foundation the divine moral law of revelation and the work of the Church in concretising that into doctrine. The distinction between top-down and bottom-up processes of doctrine formation is essential to understanding the common law, even as we recognise the vital importance of royal involvement in its development.

Norman rule was a catalyst for the birth of a new legal system that would become the common law. The fusion of Anglo-Saxon traditions and sophisticated infrastructure with Norman efficiency and desire for centralised control produced a legal order unlike any that had come before. During this time, the methods and characteristics of a common law were beginning to emerge. But this was not a smooth transition. By the time of Henry II, the ever expanding empire of laws and the uneasy coexistence of Anglo-Saxon and Norman custom had resulted in considerable breakdown in the administrative apparatus that had been so effective in the past. Overlapping jurisdictions resulting from the interaction between distinct legal traditions and a proliferation of local ecclesiastical and civil courts resulted in an administrative nightmare.

To make things worse, Henry II was faced with a monumental task of pacifying a fractured kingdom, still recovering from the civil war. He took his coronation oat to ensure justice and peace for his realm very seriously and so embarked on a project of conservative transformation; consolidating and building upon the legal norms proven to be effective without attempting radical change: he abolished nothing, but succeeded in combining all the local customary laws into a law common to the country as a whole. This was innovation cloaked in tradition, a hallmark of the common law.

The most important contribution Henry II made to the foundation of the common law was not in promulgating a new set of doctrinal rules but in reasserting royal authority by revolutionising the administration of justice, supressing the power of local sheriffs, and extending the reach of royal authority over the whole kingdom. By 1175 he had created a stable national system of ‘general eyres’ whereby itinerant judges – iusticiarii in itinere – would travel the Kingdom in circuits to hear Pleas of the Crown, promulgate and enforce new legislation, and review the effectiveness of local administration of justice. For this, Henry II was dubbed ‘law-giver’, not because he promulgated vast codes of new legal rules, but because his royal judges succeeded in usurping the power of local administrators and courts to unify the legal system into a coherent whole.

Henry II radically transformed the status and role of the judge. By the late 1170’s the royal justices in eyre had the power to make judgements themselves in what had become a local session of a national royal court. They were beginning to develop their own independent authority. Judges were royal appointees and so were freed from local allegiances. Yet they were also no longer mere mouthpieces of the King, but were rather interpreters of his justice.

Legal doctrine began to be developed primarily at the hands of the judges: if it originated in royal diktat, it developed as a result of discretionary power which Henry II had conferred on his justices, each striving for consensus and collective wisdom. Individual royal justices were beginning to form into a corporate body: the judiciary. While this body was not yet bound by the doctrine of precedent and not yet required to provide reasoned judgments, the distinct character of the common law court was beginning to take shape In particular, long established features such as the foundation of law within custom, its connection to the duty of a Christian king to provide justice, and its continuity with the past were now channelled within an institutional apparatus capable of fulfilling the promise of a common system of justice, rooted in the traditions of the land.

By the time Glanvill was compiled, the administrative changes brought by Henry II, including a seismic overhaul of the writ system, had cleared the way for the gradual development of legal doctrine which could genuinely be described as a rational and national legal system. The result of these reforms was a renewed expectation that the provision of justice was the duty of a Christian King. In consolidating royal authority, Henry II reasserted the king as the guarantor of justice and in so doing, placed inherent limits on what could be done in the name of royal justice. Justice was not the king’s gift but his duty, and in time this kernel of wisdom would develop into the rule of law tradition that the common law is famous for.

Since then, the common law has seen several canonical writers, operating in a remarkably similar fashion to the Roman jurists, from Bracton to Coke to Hale to Blackstone and even arguably to Dicey, in many ways the last of the common law’s institutional writers. What these men wrote about the common law became authoritative interpretations of the common law, sources for judicial decision-making which continue to carry weight today. The common law has its own tradition of jurists. But this, like many aspects of the common law, has classical roots. The common law emerged and found authoritative enforcement as part of a national structure at the hands of an Angevin King, but its constituent parts were handed down by its pre-Norman ancestors.