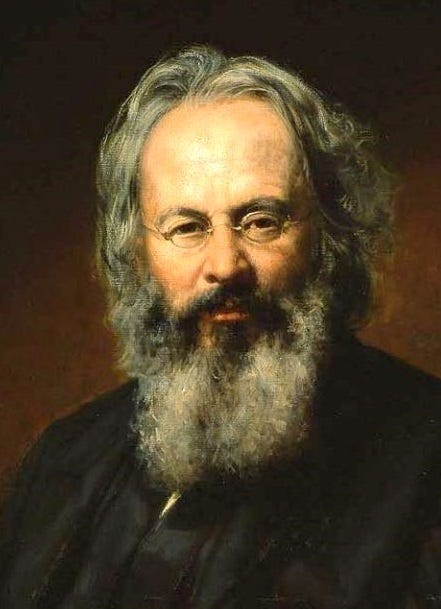

Orestes Brownson

The New Digest is pleased to feature this guest post from Max Longley. Longley is the author of For the Union and the Catholic Church: Four Converts in the Civil War (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2015); Quaker Carpetbagger: J. Williams Thorne, Underground Railroad Host Turned North Carolina Politician (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2020); and many articles.

Before the Civil War, the United States had a fight over the status of slavery under the federal Constitution (and other laws). Many antislavery jurists, activists and politicians entered the debate advocating the position that slavery was contrary to the natural law, and that the positive law of the Constitution should be read as far as possible to harmonize with natural law’s antislavery principles.

Catholic participation in this legal antislavery movement was unfortunately extremely limited. Only a handful of Catholic figures took part, outweighed by American Catholics who attempted to justify their inaction, or even support, for the systematic enslavement of Africans and their descendants by tendentious appeals to theology and canon law. It’s all the more important, then, to recognize those Catholics who correctly grasped slavery’s inconsistency with natural law and contributed to antislavery constitutionalism. But it’s not possible to examine the varieties of antislavery constitutionalism without looking at the non-Catholic versions of such teachings, which were often influential. The Catholics who joined non-Catholics opponents of slavery in antislavery constitutionalism were few in number, but were among the wisest of their generation in the American church.

Developments in Europe seemed to foretell an American Catholic contribution to antislavery thought. In 1839, Pope Gregory XVI issued the bull In Supremo Apostolatus, which denounced the African slave trade and rejoiced that Europe had allegedly eliminated slavery in the Middle Ages.[i] Many lay European Catholics followed up on this and confronted the difference between forms of servitude or punishment as approved in the theological and canon-law books, on one hand, and slavery on the other, especially the systematic slavery of people of African descent in the Americas. One of the prominent Catholics who spoke against the American slave system was Daniel O'Connell, the “Liberator” of Ireland, who had a strong following among Irish-Americans. O’Connell’s American influence on the subject of slavery was disappointingly small, and was blunted in part by an unfinished set of letters by Bishop John England of Charleston, South Carolina, about the compatibility of slavery with Catholic teachings and denying the charge that Catholics were plotting to get rid of American slavery.[ii]

For various reasons, American Catholics went the way of Bishop England, at a minimum refusing to act against slavery and at worst defending the institution. A form of Americanism developed in which clergy and laity closed themselves off from Catholic antislavery trends in Europe. During this same antebellum period, non-Catholic opponents of slavery in the United States took on the question of the American Constitution and its relationship to the Peculiar Institution. With the important exception of the Garrisonians, who gleefully alleged the Constitution’s proslavery character, abolitionists and other opponents of slavery proclaimed slavery’s hostility to the natural law, and sought to interpret the laws, especially the federal Constitution, to reflect this opposition. The positive law, they said, should only be read to conflict with the natural law when strictly necessary.

That slavery in the Southern American states violated natural law was not only accepted by American Catholics who opposed intervention against slavery, but even those who defended the institution.

Bishop Augustin Vérot, Vicar Apostolic of Florida, gave a sermon in January 1860, amid the Secession Winter, both admitting the anti-natural-law components of the actually-existing slave system in the South while trying to offer a theological defence of the institution. After defending slavery as traditionally approved by Catholic canon law and other theological sources, Verot denounced bigoted Northern Protestant attacks against the enslavement of the descendants of Africans in the United States – claiming that the personal liberty laws of the North in defense of alleged fugitive slaves was a major contributor toward bringing disaster and civil strife to the country. But Verot’s was a Janus-faced sermon, which halfway through began to describe certain evils which were so attached to Southern slavery as (one might think) to make it indefensible on natural-law terms. Verot listed the violation of the rights of free blacks, the rape of black women, the failure to respect marital bonds among the slaves. These would all prompt stern divine vengeance if left uncorrected, said the bishop. But to Verot, as to many intellectual defenders of African slavery, the institution should remain in place even while people like the Florida bishop pleaded (in vain, it turned out) for Southern laws removing the abuses. On the constitutional level, Verot said the North’s personal liberty laws contradicted the fundamental law, but he did not explain the legal basis of his views. The personal liberty laws, to protect alleged fugitives from federal seizure, affirmed the fugitives’ right to jury trial and habeas corpus, which the federal Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 denied them, but which the Constitution secured to them.[iii]

Even Charles O’Conor, a prominent New York lawyer who exerted all his forensic skill to defend American slavery in an 1859 speech, implicitly acknowledged that slave owners sometimes acted with “harshness and inhumanity” to their slaves, without being punished. O’Conor said that this deplorable situation was only because the South felt on the defensive against Northern attacks. The South would punish the cruel masters just as soon as the North let Southern slavery alone. Such was O’Conor’s rationalization.[iv]

The banner of antislavery constitutionalism was taken up by non-Catholics. In the 1840s, Ohio Whig Congressman Joshua Giddings put these ideas to the test, at great political risk to himself. Blacks on the American coastwise slave ship Creole had rebelled, and the U. S. government pressed Britain for compensation for giving shelter to the rebels. Giddings introduced a resolution in Congress avowing that slavery, being a positive-law institution existing only in the slave states, did not extend to the high seas, outside slave state jurisdiction. The House censured Giddings, though he was promptly re-elected by his constituents.[v]

The abolitionist Liberty Party was founded at this time and advocated a “divorce” between the federal government and slavery. The party’s efforts would not be focused on the slave states, but on federal policy. Federal authorities, it was proposed, would no longer promote slavery or maintain it in the national territories or Washington, D. C., or advance proslavery policies in any way. In 1848, “moderate” members of the party, notably Salmon Chase (dubbed by some the “attorney general for fugitive slaves”) left for the more broad-based Freesoil Party, which focused on keeping slavery out of the federal territories, then becoming the flashpoint of slavery arguments in the United States. Chase, later one of the most prominent “radicals” in the Republican Party, was described by some as advancing a doctrine of “slavery sectional, freedom national,” which claimed that the Constitution allowed slavery on the state level but not on the federal level. The “freedom national” doctrine as articulated by Chase extended beyond the federal territories and included the fugitives-from-service clause in the federal Constitution. Instead of federal officials chasing fugitives, the clause, in this view, only allowed enforcement of this provision on the basis of interstate comity. In reality, federal police and courts vigorously pursued alleged fugitives in the North until the outbreak of war.[vi] Chase’s “radicalism” did not persuade all Republicans, except on the flashpoint issue of territorial slavery. Still Chase would go on to become Secretary of the Treasury and then Chief Justice.

Meanwhile, the even more “extreme” rump of the Liberty Party, unembarrassed by comparative moderates like Chase, could now take an advanced antislavery position (ending up at the Radical Abolition Party). The party adopted the arguments of abolitionist lawyer Lysander Spooner. Spooner’s book on the unconstitutionality of slavery was recommended by the Liberty Party platform for study by lawyers. Spooner not only took the position that the positive law of the Constitution should be interpreted, in all cases of ambiguity, as supporting the antislavery provisions of the natural law. This was standard in many antislavery circles. But Spooner went on to discover ambiguities where other antislavery lawyers didn’t find them – the three-fifths clause (it didn’t refer to slaves!) and the fugitives-from-service clause (it didn’t refer to slaves either!). In general, Spooner found constitutional support for slavery’s unconstitutionality in the states as well as under federal jurisdiction. Supported by Frederick Douglass, and by financial angel Gerrit Smith, the Liberty/Radical Abolition party provided a home to the most committed of the antislavery constitutionalists.[vii]

On a more “mainstream” level, William Henry Seward was less radical but was deemed radical enough to antagonize the slave interest. The Senator from New York, in a speech in the slavery debate of 1850, focused on slavery in the territories, citing the Constitution’s preamble to say the fundamental law consecrated the territories not to slavery but “to union, to justice, to defense, to welfare, and to liberty.” Not only did the Constitution require this, but “there is a higher law than the Constitution, which regulates our authority over the domain, and devotes it to the same noble purposes.” Seward’s proslavery enemies accused him of setting the higher law – or, the natural law - above the Constitution. In fact, what Seward was doing was what natural lawyers had always attempted to do: harmonize the positive law and the natural law, declaring that both pointed in the same antislavery direction.[viii]

An example of the harmonization of an antislavery vision of the law of nature and of nations with the Constitution occurred in Ohio in 1860. The governor of Kentucky wanted the extradition of Willis Lago, accused of helping a slave escape the state. Ohio’s governor, William Dennison, backed by state attorney general Christopher Wolcott (who would serve in the Civil War’s War Department until his death), replied to the demand. Walcott’s opinion, supported by Dennison, confronted the constitutional clause requiring the state to extradite accused criminals from other states. Wolcott said this obligation did not apply if the alleged offense was “regarded as malum in se by the general judgment and conscience of civilized nations.” Such was the case with laws punishing slave-rescuers, so Kentucky’s demand was rejected (the Supreme Court rebuffed Kentucky’s challenge, on jurisdictional grounds, in the prominent decision Kentucky v. Dennison on the eve of the war).[ix]

In the same year, the Republican Party platform displayed the influence of antislavery constitutionalism. Focusing its moral energy on keeping slavery out of the territories, the platform said that territorial slavery would unconstitutionally deprive the slaves of liberty without due process of law – hence slavery could not legally exist in the territories.

For the Catholic contribution to antislavery constitutionalism, we turn to the mercurial Catholic intellectual Orestes Brownson, editor of Brownson’s Quarterly Review. Brownson’s was a curious case. In his earlier political writings at the time of his 1840s conversion, he had endorsed his hero John C. Calhoun’s view that Congress could not keep slavery out of a territory. By 1857, Brownson continued to deny that Congress could interfere, but now he believed that the Constitution banned territorial slavery even if Congress claimed to make it legal. Brownson attributed his change of view to a Supreme Court decision “that slavery is a local institution, existing only by virtue of the positive law.” But in 1857 the Supreme Court issued quite a different decision, and Brownson opposed this new ruling.

The ruling was Dred Scott, which not only provided a legal basis for territorial slavery, but also denied the citizenship of black people. Brownson was appalled that a Catholic Chief Justice – Roger Taney, author of the lead opinion in Dred Scott – could ignore the Catholic and natural-law principle of the unity of the human race, as well as proclaim in favor of slavery in the territories.[x]

Brownson’s assurances that he remained a racist did not shield him from criticism from other Catholics. The slavery-appeasing (and future Copperhead) New York editor James McMaster, with his popular Freeman’s Journal, supported Dred Scott and could be considered more influential than Brownson among American Catholics.[xi] The Boston Pilot, affiliated with the Boston diocese, criticized Brownson for suggesting that Taney should have brought his religion into the Dred Scott decision. The Pilot said the Court’s “imperative duty” was to ascertain whether “the public opinion of 1787” was “codified and expressed in the fundamental law of the nation” and, if so, to rule accordingly regardless of supposedly extrinsic considerations like humanity and religious teachings on freedom.[xii]

Another of our Catholic commenters would have also incurred the Pilot’s wrath. Judge William Gaston (1778-1844) of the North Carolina Supreme Court[xiii] was a prominent member of his state’s political establishment, not only in spite of his Catholic religion but in spite of his publicly expressed antislavery views. In 1832, he urged students at the state university to work for the end of slavery, which he said “poisons morals at the fountain head.”

As a judge, when the law was vague, Gaston resolved it in favor of the rights of slaves and free blacks. He affirmed the right of slaves to resist deadly attacks from slave owners and replied to the claim denying such a right thus: “Unless I see my way as clear as a sun beam, I cannot see that this is the law of a civilized people and of a Christian land.” This is the style of reasoning the Pilot had praised Roger Taney for not adopting.

Judge Gaston also affirmed the citizenship of free blacks (contradicting Taney’s later Dred Scott ruling), limited the legal scope of permissible forms of corporal punishment for slaves, and defended manumission. In a non-slavery-related dissent, Gaston affirmed the responsibility of judges “to hand down the deposit of the law as they had received it without addition, diminution or change.” Gaston seems to have been thinking, by analogy, of Catholics’ responsibility to the deposit of the faith.

On the subject of slavery and race, Gaston only intervened in favor of human rights when the law seemed to leave room for the interpolation of natural-law principles. But on the subject of his own eligibility for political office in North Carolina, Gaston and his supporters adopted a distinctly “Spoonerist” approach to the law. The state constitution forbade officials from “deny[ing]…the truth of the Protestant religion.” While Gaston and his allies acknowledged that this was probably meant to keep Catholics out of office, they borrowed Spooner’s ultra-skeptical interpretive methodology and decided that the “Protestant religion” referred only to common-denominator beliefs held among all Christians (the Resurrection, etc.). To decide otherwise would be to deny the people the right to the service of worthy citizens. (The voters specifically allowed Catholics to hold office in 1835, inspired by Gaston, while rejecting Gaston’s plea for full religious equality for Jews, deists and Muslims).

As shining lights of antislavery, natural-law constitutionalism, Brownson and Gaston may seem like outliers within American Catholicism. By the time Abraham Lincoln won the Presidency on a moderate platform of constitutional antislavery, most American Catholic leaders were still anti-anti-slavery or even proslavery. They considered the Constitution a proslavery document endangered by Northern radicals (whom they associated with anticatholic Protestant preachers, probably of New England origin).

Lincoln’s antislavery constitutionalism was more “moderate” than Chase’s, to say nothing of the views of the Radical Abolition (Liberty) Party. Lincoln focused on the key issue of slavery in the territories, and spoke in terms of the Declaration of Independence as a sort of stand-in for natural law, forbidding territorial slavery. Lincoln’s views were radical enough from the South’s standpoint, leading the Confederate states to secede and fight a Civil War. It was during the war that American Catholics began (in some, not all cases) to grow more open to attacking slavery. Orestes Brownson, and the spirit of William Gaston, were there to welcome these additional Catholic recruits to the fight against slavery and to what the natural law and Catholic teaching truly demanded.

[i] In Supreme Apostolatus, https://www.papalencyclicals.net/greg16/g16sup.htm.

[ii] John England (George Read, ed.), Letters of the Late Bishop England to the Hon. John Forsyth, on the Subject of Domestic Slavery. Baltimore: John Murphy, 1844.

[iii] Augustin Verot, A Tract for the Times: Being the Substance of a Sermon, Preached in the Church of St. Augustine, Florida, on the 4th Day of January, 1861, day of Public Humiliation and Prayer (no date or place of publication given). Thomas D. Morris, Free Men All: The Personal Liberty Laws of the North, 1780-1861. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1974.

[iv] Charles O’Conor, Negro Slavery Not Unjust. New York: Van Evrie, Horton and Company, [1860?]; “Charles O’Conor,” https://www.newadvent.org/cathen/11202a.htm.

[v] Bruce Chadwick, The Creole Rebellion: The Most Successful Slave Revolt in American History. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2022, 169-75.

[vi] Reinhard O. Johnson, The Liberty Party, 1840-1848 Antislavery Third-Party Politics in the United States. Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 2021; James Oakes, Freedom National: The Destruction of Slavery in the United States, 1861-1865. New York: W. W. Norton, 2013.

[vii] Lysander Spooner, The Unconstitutionality of Slavery. Boston: Bela Marsh, 1847; Randy E. Barnett, “Was Slavery Unconstitutional Before the Thirteenth Amendment?” 28 Pacific L.J. 977-1014 (1997); “1849 Platform of the Liberty Party: Adopted in Convention, 3 July 1849, Cazenovia, N. Y.” http://alexpeak.com/twr/libertyparty/1849/.

[viii] Walter Stahr, Seward: Lincoln’s Indispensable Man. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2012.

[ix] Stephen R. McAllister, “A Marbury v. Madison Moment on the Eve of the Civil War,” The Green Bag, 14 GREEN BAG 2D 405.

[x] Patrick W. Carey, Orestes A. Brownson: American Religious Weathervane. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2004; Max Longley. For the Union and the Catholic Church: Four Converts in the Civil War. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2015.

[xi] Max Longley, “The Radicalization of James McMaster: The ‘Puritan’ North as an Enemy of Peace, the Constitution, and the Catholic Church,” U. S. Catholic Historian, Volume 36, No. 4 (Fall 2028), 25-50.

[xii] “Brownson’s Review. A Taint of the Old Leaven,” Boston Pilot, Volume 20, Number 15 (11 April 1857),

[xiii] J. Herman Schauinger, William Gaston: Carolinian. Milwaukee: The Bruce Publishing Company, 1949.