If readers of the New Digest have not already done so, I heartily encourage them to read or listen to my friend Adrian Vermeule’s Vaughan Lecture, delivered at Harvard Law School in October 2022. The lecture - entitled ‘The Original Scalia’ - offers a fascinating account of how the jurisprudential commitments and worldview of Justice Antonin Scalia were, for much of his academic and judicial career, quite classical. Vermeule then contrasts this earlier period of Justice Scalia’s jurisprudence, which he dubs ‘Original Scalia’, with his approach in the latter stages of his career, where Vermeule argues his jurisprudential worldview became “flattened and simplified” and further from its classical origins.

I’d further encourage readers to parse the back and forth between Vermeule and Professor Lawrence Lessig, his colleague and one of those invited by the organizers to respond to the lecture. In his interesting remarks, Lessig says that Vermeule’s “extraordinary” book Common Good Constitutionalism and his positive assessment of ‘Original Scalia’ are both invitations to “reimagine—so we might practice again—the classical model of law. In this classical model, law is both lex—what legislatures, presumptively, write—and ius—the principles and traditions and morals behind that lex.” Pessimistically, however, Lessig went on to suggest that any attempt to retrieve a more classical worldview within the United States is likely to crash hard on the rock of the social fact that “our legal culture today is not the culture that the classical model presumes. Whether justified or not, our culture today, our legal culture, is deeply suspicious. Profoundly skeptical.”

In his rejoinder, Vermeule probed the references to “we” and “our” in Lessig’s comments, querying if the legal-realist culture to which Lessig referred was American legal culture in any broad sense, or rather the legal culture of a “very small set of academics at a very small set of elite schools who are committed to a virulent form of legal realism that thinks “politics” determines all interesting judicial decisions, at least in hard cases.” In Vermeule’s view, the success of this form of legal realism is simply not a given or matter of fact, but a “product that law professors push on their students, a kind of intellectual opiate that the recipients resist until they become addicted to it. There is no deep underlying reason why this process of acculturation into legal realism must occur in the first place; it is a choice we make, and we could do otherwise.”

I think this exchange raises fascinating questions for anyone interested in debates over the possibility of reviving the classical legal tradition within legal thought and practice. Namely, is it possible to revitalize the tradition and its accompanying epistemological and ontological assumptions amongst lawyers, students, and judges, in circumstances where they all seem profoundly heterodox amongst many elite actors? How would this revival even come about?

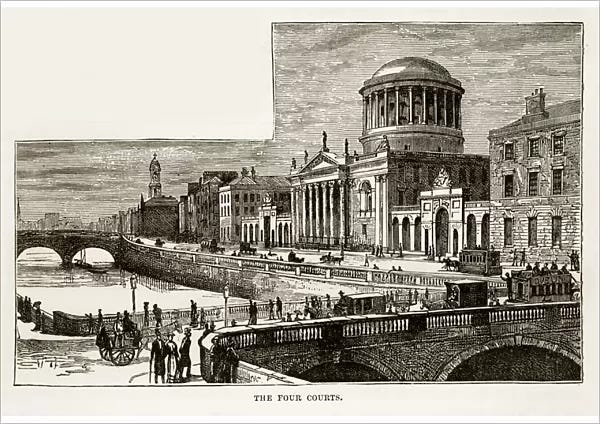

In this post I would like to offer a modest case study of sorts, based on the experience of my home jurisdiction of Ireland, that might shed some light on the path this kind of revival might take.

As many have documented, Irish legal practice – reflected in the argumentation and reasoning of lawyers, jurists, and judges – has, for much of the existence of our Irish constitutional order, firmly reflected a distinctive jurisprudential ethos and worldview steeped in the classical legal and natural law tradition. This is a mindset and worldview that regards positive law like constitutional text as part of a broader web of law also including principles of legal justice stemming from the natural law; that accepts that these different sources of law should be harmonized wherever possible; that views the purpose and point of state power as promoting the common good; that regards rights as a necessity for human flourishing, but understood they had to fit within the overall context of the common good, and that puts a premium on subsidiary institutions like the family.

This, however, was not the case for around thirty years of the Constitution’s existence. Many readers will be aware that the 1937 Irish Constitution is a document suffused in Aristotelian-Thomistic thought, which commits the state to promote the “the common good” as its end, guided by values of “prudence, justice, and charity” so that the “freedom and dignity” of the individual and inalienable and imprescriptible rights of the family can be secured. But readers will perhaps be surprised to learn that the enactment of the 1937 Constitution did not spark a classical legal revival overnight. Far from it. In fact, until the mid 1960’s many of the Constitution’s classically influenced provisions were simply rarely deployed by lawyers and not commented upon by judges. In some respects, however, the rather dull impact of the Constitution was unsurprising; for its jurisprudential commitments were initially quite at odds with the prevailing outlook of the academy, bench, and bar, which were largely ambivalent to the natural law tradition’s relevance to legal practice. The Constitution and its impressive textual commitments, therefore, did not, at first, do much at all to alter the mindset of a judiciary and legal profession brought up and educated with the presuppositions of positivistic 19th-century English jurisprudence.

The modest impact of the Constitution would have come as no surprise to the likes of Edward Cahill SJ, a Jesuit and political theorist who provided input and suggestions to Eamon De Valera during its drafting. At one point during the drafting process, Cahill unsuccessfully urged De Valera to insert an interpretative clause explicitly stating that the Constitution’s provisions would be interpreted in harmony with the dictates of natural law. Cahill’s motivation for inserting this provision stemmed from his fear that terms in the Constitution like “common good” “social justice”, “personal rights” and “property rights” were in real danger of being interpreted inconsistently with the natural law tradition that inspired them. Cahill feared they would either be treated as dead letters or in light of the “individualistic and liberal principles” of English jurisprudence most Irish judges and lawyers were schooled in. The fact most judges and lawyers were Catholic - and so in their personal lives presumably thought natural law precepts were of immense moral relevance - clearly had little impact on their jurisprudential views as to their legal relevance.

This picture of Irish legal culture would change utterly, and with remarkable speed, in the mid-1960s when a new generation of lawyers and judges well-versed in the natural law tradition, rose to prominence. This group included some of the most acclaimed Irish jurists of the 20th century, including Donal Barrington, Declan Costello, Seamus Henchy, Cearbhall Ó Dálaigh, John Kenny, and Brian Walsh. All of these jurists were educated at University College, Dublin in the 40s and 50s against an intellectual backdrop of the flourishing of Irish natural law thinking. Many of the jurists of Ireland’s classical legal revival were deeply impacted by the instruction of the likes of Professors Daniel Binchy and Patrick McGilligan. More generally, this new generation was also doubtless impacted by the totalitarian horrors of the early 20th century and believed that the reaffirmation of natural law thinking represented a critical bulwark in protecting human dignity from both the dangers of laissez-faire liberalism and state authoritarianism.

The former of the two jurists was a diplomat and famed scholar of jurisprudence and Roman law and a fierce critic of legal positivism. A lecture of Professor Binchy’s entitled “Law and the Universities” published in 1949, gives us a good insight into how he approached legal education. He argued that jurisprudence was the “lynchpin” of all higher legal studies and its purpose should be to provide a “trait d’union between the profession of law and the philosophical and ethical principles from which alone legal systems derive their ultimate validity”. As the Irish ambassador to Germany in 1932, Professor Binchy was a first-hand witness to the rise of National Socialism and their brutal disregard for law and justice. Writing in 1949 in the terrible afterglow of WW2, Binchy feared that unless lawyers and legislators returned and cleaved to the classical concept of positive law (the concept he says runs from “Plato and Aristotle, through the Roman jurists and the medieval Schoolmen, down to the neo-Scholastic philosophers of our own day”) whose “ultimate sanction lies not in a command of the State but in its conformity to a transcendental idea of justice” then disastrous consequences for law and politics would inevitably follow. For Binchy, the legal order could only thrive and contribute to the common good “if our professional lawyers (and our legislators) are equipped with a sound theory of law on which to base their approach to concrete problems”.

The latter, Professor McGilligan, was UCD’s Professor of Constitutional Law from 1934-1959. McGilligan was a firm proponent of natural law reasoning in constitutional adjudication, dubbing principles of natural law the 1937 Constitution’s “sheet anchor” and not something that could be considered irrelevant to legal practice. Writing extrajudicially, the current Chief Justice Donal O’Donnell has noted how “almost all of the judges in the High Court and the Supreme Court during the 1970s and 1980s were taught constitutional law by McGilligan” and his views on the relevance of natural law thinking to adjudication would have a profound effect on their work.

Perhaps the most revolutionary contribution made by the generation of judges and lawyers educated in UCD during this time was their spearheading of the use of natural law precepts and the Constitution’s background principles of legal justice during constitutional adjudication, to better let them determine the meaning of its posited text and structure in hard cases – to ensure harmony between lex and ius. This contribution would precipitate a sea-change in Irish legal practice whose effects are still felt today. The aftershocks of this natural law revolution still - even now - continue to help insulate Irish legal practice and constitutional jurisprudence from the influence of the pernicious neoliberalism that increasingly dominates other areas of political life. A prominent example involves jurisprudence concerning parental autonomy and the rights of the family vis-à-vis the state in the domains of education and healthcare choices, which continue to sound strong classical notes. Considerations of background principles of legal justice were also key, for instance, to the Supreme Court holding the line against libertarian individual autonomy-based arguments for a right to assisted suicide in Fleming v Ireland [2013] IESC 19, and in a string of important cases vindicating the dignity and person of vulnerable groups of citizens like prisoners subject to terrible conditions, asylum seekers, and the profoundly disabled. The classical natural law tradition is also deeply prevalent in jurisprudence affirming that the common good is the proper end of constitutional government; that the executive and legislature have ample authority to pursue this end and to order individual goods like property to it; and that all legitimate exercises of public power should be presumed to be purposive and reasoned and not mere arbitrary assertions of will.

What light, if any, does this short Gaelic vignette shine upon the questions I posed at the beginning? How, in other words, does it speak to the Vermeule-Lessig back and forth about whether a classical legal revival is even possible in a system where the natural law tradition is moribund, in retreat, or endures as a minority insurgent faction? Bearing in mind all the (many) caveats that must attend to any comparison of the legal culture of a small island nation and a sprawling superpower, I think we can at least say the remarkable revolution in Irish legal culture in the 20th century offers some encouragement to the classical lawyer.

One lesson is that significant shifts in legal culture can be sparked by small, dedicated, groups of jurists. The Irish legal revolution began humbly enough, in debates and discussions in lecture halls and seminar rooms. A small but enthusiastic band of classically minded scholars and teachers were able to expose their students to the axioms and presuppositions of the natural law tradition – that of Aristotle, Aquinas, and the Roman jurists – a tradition that up until that point previous generations of Irish law students, reared on a diet of Austin and Dicey, may never have been exposed to. The more receptive students then enthusiastically carried the core principles of the tradition into their own work, whether as scholars or practitioners - further diffusing what they had absorbed during their legal educational formation. Finally, when many of these students eventually made their way onto the Bench, they were able to transform Irish public law by putting into operation the jurisprudential commitments and worldview that had been so central to their formation as jurists, and for the first time unlocked the potential of the Constitution and its classical commitments.

Today, then, while we may justly regret that the classical tradition in the United States lacks now that strength which in old days carried all before it, we should take heart from the fact there are many law students, current and future, that are hungry for, and curious about, legal approaches more intellectually and morally satisfying than positivism or legal realism. The Irish example suggests to me, and I hope to our American readers especially, that if this hunger can be met, and curiosity satisfied, even by a small but dedicated band - then the results could be seismic in the decades to come.

Thank you Prof Casey for a convincing summary of the exchange between Prof Lessig and Prof Vermeule on CGC, plus a review of lessons learned from the Irish Natural Law Revolution.

If I may offer my own modest thought: Prof Vermeule’s analogy to “Intellectual Opiate” of a genre of jurisprudence that dedicates itself to serving what trends or what has greater appeal to prevailing socio-cultural-political winds is most apt, for indeed “there is no deep underlying reason why the process of acculturation into legal realism must occur in the first place”. I put it thus: Mass is not sufficient reason to redirect the course of Law. Were this not true, then mass is law, not law.

I also note opiates quell the symptoms of psychological distress. It does not cure the cause(s) of the distress. Furthermore, opiate-dosing used to quell chronic distress need be constantly increased when the use morphs into a HABIT, in order to achieve the same “effect” of the previous dose.

The Q therefore becomes this: When will this acculturation process end? In the opiate analogy, a point is reached where increasing dosing will reach the point pf overdose. Overdose poses a great risk of harm to the user, including cessation of life.

In terms of Prof Lessig’ pessimism re how CGC, though admittedly not a bad idea, will “crash hard” on landing given current prevailing cultural-political winds, I submit the alternative Prof Lessig suggests has already crashed, and crashed harder than CGC ever will. Again, take a look at what is real before our eyes. What is real has greater credibility valence than what is not real.

Lastly, Law is the architect of the essential structures of a human society. It is also the teacher of the people in the society. As an architect, a falling-apart classroom is not a reason to tear down the support beams of the classroom. As a teacher, unruly pupils are not good enough reasons to abandon the duty of a teacher. The choice may be difficult, but nobody ever says it is easy for a leader to prove his mettle.

cc: Adrian Vermeule