On March 3, 2022, Judge Rao of the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit gave the Sumner Canary Memorial Lecture at Case Western Reserve University, which has now been published. Her lecture, entitled Textualism’s Political Morality, sets out to “explore the political morality that undergirds and informs a textualist approach to statutory interpretation" and then to contrast textualism favorably against “methods of interpretation that rely on the judge’s abstract normative values about justice or fairness or that seek to update statutes in accordance with evolving social or political norms.” In her opening remarks, Judge Rao says that her defense of textualism is “especially timely” given critiques advanced by what the judge refers to as a “wave of post-liberal scholars” (mentioning one of us by name) who have suggested that “laws should be interpreted to promote the ‘common good.’” Judge Rao’s subsequent critique of common good constitutionalism and its classical approach is anchored on the premise that its proponents think “judges should give effect to certain substantive values, values that exist independently of the law” and that “should interpret statutes in light of principles found outside the law” because “such principles will lead to ‘better’ results than simply following the text” (our emphases).

This is, rather trivially, not at all the classical legal position held by common good constitutionalists; the classical view has always been that background principles of legal justice are themselves internal to law. As Vermeule wrote in his recent book, the principles to which the classical tradition looks “are themselves already part of the law and internal to it.” Or, as John Finnis puts it, such principles are ipso iure, meaning that they are themselves part of the law. All this is familiar and uncontested, or ought to be. H.F. Jolowicz explained long ago that for the Roman lawyers, aequitas or equity was not a “contrasting principle” to law, but a mode of interpretation within law.

But in this post, we want to do more than highlight Judge Rao’s misunderstandings. If Judge Rao merely misunderstood what the classical view holds, her lecture could neatly join a crowded shelf of off-the-bench efforts at legal theory by originalist judges, which we have discussed elsewhere, and which are also crippled by a question-begging stipulation that the classical legal tradition does something other than law.

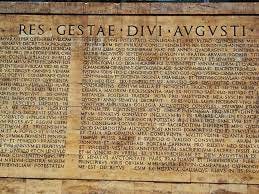

What we find more interesting, and which raises her argument to an apparently unintended form of high art, is that she then proceeds to recreate the classical view itself, seemingly without knowing that she is doing so, and under a different label. In so doing, Judge Rao has continued a recent trend, in which textualists have in effect allowed a kind of Augustan settlement of our law. Like the senators and optimates of Rome under Augustus, they have been content with retaining the outward forms and labels of the regime to which they are wedded, while ceding the operative content of the law to rule by other principles.

For a start, Judge Rao’s own views on textualism are entirely distinct from those held by the most prominent textualists on the Supreme Court. For example, at no point in the lecture does Judge Rao endorse the Gorsuchian position that “[o]nly the written word is the law”. Nor is Judge Rao’s position in her lecture consistent with then-Judge Amy Coney Barrett’s view, articulated while giving the 2019 Sumner Canary Memorial lecture, that textualism is fundamentally about “identifying the plain communicative content of the words” of posited text. For Judge Barrett, the crux of textualism is that “textualists limit the meaning of text to the semantic communicative content (in context) of the words themselves” because “the law can mean no more or less than that communicated by the language in which it is written.” Yet now-Justice Barrett, like Judge Rao, has more recently opted for a highly enriched version of “textualism” by invoking an expansive version of “context” that seems to build in most of the background principles of legal justice her theory is intended to eschew. Barrett and Rao, in other words, are following a road that a number of textualist academics have recently explored, a road that ends by adopting a classical approach in all but name. We return to this point at the end.

Setting forth her affirmative view, Judge Rao defends a vision of legal interpretation that has a far richer legal ontology than her nominal textualism would suggest, or than the dictum “only the written word is the law” would allow. For Judge Rao, the “sources of legal meaning” that properly inform statutory interpretation go far beyond the plain communicative content of words, but incorporate (as she puts it) “background principles of law” that include “axioms of reason.” Indeed, Judge Rao soon begins to speak in a thoroughly classical, even a Thomist register. She argues that “the positive law incorporates legal principles and legal methods that have developed over time. These principles and methods reflect basic moral commitments and reasons…. Lawmakers act within our particular legal context. Indeed, it would be impossible to write an effective statute that could be interpreted only by reference to Webster’s Third Dictionary.” Judge Rao urges that “law and legal interpretation incorporate certain reasons, but these aren’t abstract moral reasons; they are reasons inherent to the law.” In other words, Judge Rao argues that the communicative meaning of the statutory text should be read against a very rich contextual backdrop that includes standing legal presumptions about how a lawmaker ought to act – including that they act rationally, coherently, and mindful of the entire corpus juris of the community, including principles of customary common law and indeed natural law.

It’s worth pausing over that last bit for a moment. Judge Rao is not content to say that natural law provides reasons for an authoritative settlement of positive law, a settlement that excludes judicial application of principles of natural law in particular cases - a view some other originalists have recently defended. (Vermeule discusses the flaws in that view in a forthcoming response to a symposium in the Harvard Journal of Law and Public Policy). Rao instead goes farther, much farther. Her startling references to “axioms of reason” — startling for a professed textualist, although ordinary for a classical lawyer — cashes out explicitly to include natural law at the point of judicial interpretation. As Rao puts it, “[o]ur mature and sophisticated legal tradition is built on principles of natural law, common law, and concepts rooted in the Roman law. In determining the meaning of a statute, textualists may rightly turn to these legal sources for guidance” (emphasis in original). When Rao summarizes her view by saying that “traditional sources of legal meaning in turn incorporate and reflect moral values drawn from the natural law and the reasoned working through of legal principles over time,” the Angelic Doctor himself would nod in agreement. Rao has, in effect, recreated his famous definition of law as (among other conditions) an ordinance of reason promulgated by those who have charge over the community, a fusion of reason and fiat.

What has happened here? How has Judge Rao’s textualism become enriched to the point where she has, albeit unintentionally, recreated the classical view? (A view that would no doubt be rejected by self-professed textualists, if there are any left, as contrary to textualism’s emphasis on the plain communicative meaning of the written text). Rao’s basic confusion is that she has imbibed the idea — which a moment’s thought suggests is wildly implausible, except that so many originalist outlets repeat it — that the classical view of law wants judges and other officials to apply principles of political morality as such and directly, without regard to law. As she writes, “the legal foundations that inform meaning must be postulates of law (emphasis in original). They do not include abstract moral principles or policy views.”

But no matter how hard one italicizes the word law, the idea that the judge or other official has free license to pronounce directly on “abstract moral principles or policy views” has, needless to say, never been the view of the jurists of the tradition. As C.N.S. Woolf put it in his study of Bartolus, the great Italian jurist of the 14th century, “if .. we say that Bartolus was not a political thinker, we must remember that this distinction between law and politics is rather ours than his.” The jurists of the tradition did not take themselves to be doing something other than law, yet their view of law itself incorporated background principles and structured presumptions of legality, of natural law, and a basic teleological orientation of law to the general welfare. The American framers and ratifiers, with their constant references to the unwritten “great first principles” of constitutional government, lived and breathed within a particular local variant of the tradition.

Today, proponents of common good constitutionalism want to revive this way of thinking about law and legal practice. It is inappropriate for a judge to try and displace or amend positive law by reference to all-things-considered moral decision-making, which is a usurpation of the legislative function. But following the classical tradition, when attempting to discern the meaning of posited law and the reasoned choice of the lawmaker – or lex - judges can and should have regard to those principles of legal justice – ius - that are also part of a community’s corpus juris. Such principles are not moral principles tout court but are internal to law and concerned with the maintenance of a just and reasonable ordering of persons in a political community through law and legal institutions, and of proper treatment of citizens by political authority; both of which are standing requirements of justice and the natural law. The classical tradition, therefore, incorporates a subset of political morality within the law, namely the subset bearing on the virtues of legal justice and regnative prudence, of which the common good is the object and settlement or coordination of social disputes and rational governance central but not exclusive means.

In contrast to the rich tradition from which we draw, the idea that only the written word of positive enacted texts counts as law is a very recent development — an idea to which, curiously, Judge Rao professes allegiance, but then abandons with gusto in order to construct a more plausible account. And the account she constructs is, in effect, the classical account. An unintentional surrender it may be, but it is a surrender nonetheless.

After some three years of debate over the revival of the classical legal tradition, Judge Rao’s effort, if nothing else, is a sign of the times. The debate over legal interpretation has reached a kind of Augustan settlement, in which the outward forms and labels of the textualist movement are preserved while the content is everything classical lawyers could wish. Textualists and originalists like Judge Rao, Justice Barrett and assorted academics have moved a very long way towards incorporating the classical legal tradition, although retaining, for sociological and professional reasons, the labels to which they have long been committed, and while mischaracterizing the classical view as licensing open-ended invocation of morality or otherwise doing something other than “law.” The point of the latter move is to deny that they have surrendered to the classical revival, while taking it on board in substance. From the standpoint of the classical lawyer, all this is a welcome development. If our law recovers and remembers its classical heritage under the forms and labels of textualism, enriched to the point of classicism by an expansive account of “context,” then the classical law will enjoy, like Augustus, both auctoritas and indeed maius imperium.