Codification and the Ius Commune

Emperor Napoleon I - the French Justinian?

The New Digest is thrilled to feature this guest essay by Professor Stéphane Sérafin, who is an Assistant Professor at the Faculty of Law, Common Law Section, University of Ottawa.

If Napoleon Bonaparte’s military campaigns feature prominently in a recent American film production, the ten reliefs that adorn his tomb in the Dôme des Invalides in Paris point primarily to his significance as a legal and administrative reformer. On this list of accomplishments, his role in the drafting and enactment of the French Civil Code of 1804 perhaps ranks highest of all. Although it was not the first attempt at systematically reducing the whole of the civil law into a single unified document, Napoleon’s conquests ensured that the Code became the basis of the civil law of most other countries in Western Europe. Even the English drew heavily on the Code in the development of their common law, as attested by still-leading cases such as Hadley v Baxendale. Only the German Civil Code, enacted in 1900, can claim to have been transplanted into a greater number of foreign jurisdictions.

It is perhaps unsurprising that, as with Napoleon himself, the extent to which the Civil Code of 1804 stands in rupture or continuity with the French Ancien régime has been the subject of persistent controversy for more than 200 years. In this post, I set out arguments on both sides of this issue, daring to suggest that the only plausible conclusion is an ambivalent one. One the one hand, there is a large degree of truth to the claim that the Code is in continuity with the ius commune that was directly applied in the South of France and heavily influenced the customary law of the North prior to the French revolution. But on the other, the form of the codification introduced by the Code of 1804 presents a quite radical break with all that had come before, by replacing a tradition that claimed universalism subject to local variation with a series of national or in some cases sub-national enactments that are thought to merely share in the same historical influences.

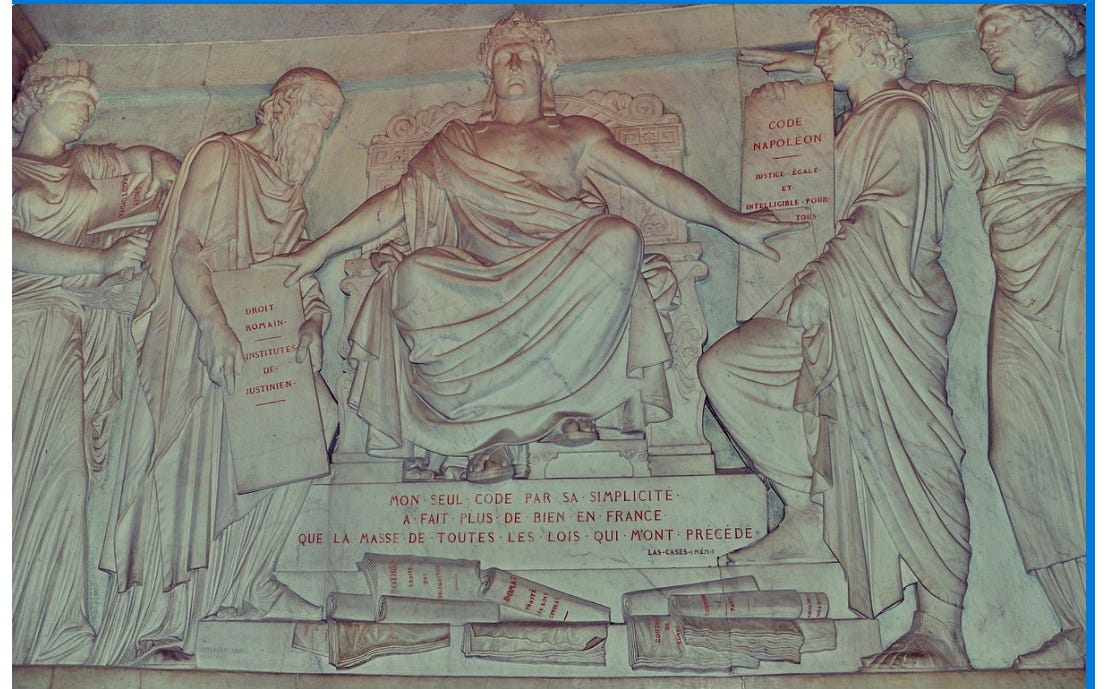

Perhaps the strongest evidence of the Civil Code’s ambivalent relationship with the ius commune can be found in the story that French jurists even today like to tell themselves about its enactment, which is conveniently summarized in one of the ten reliefs that adorn Napoleon’s tomb. As that relief celebrates Napoleon’s enactment of the Code, we quite fittingly find him pointing, on the right-hand side (his left) to a raised-up slab inscribed with the words “Code Napoleon” and “Equal and Intelligible Justice for All”. On the left (Napoleon’s right), we find him pushing himself up by simultaneously pushing down on another slab bearing the words “Roman Law” and “Justinian’s Institutes”. And at Napoleon’s feet, discarded, are the works of the French jurists Jean Domat and Robert-Joseph Pothier, on which the work of the codifiers had heavily drawn, as well as the local customs of the North of France, such as the Custom of Paris, which the Code had served to displace. The caption at the centre of the relief, finally, serves to tie the whole of its message together: “My Code alone by its simplicity has done more good in France than the whole mass of laws that have preceded me.”

The purpose of the codification project, at least if the relief is to be taken on its face, was thus not to depart fully from the various sources on which it drew, but to render them obsolete by distilling their central ideas into a simpler, more accessible form. In this respect, the intention underlying the Code was not all that different from that underlying Emperor Justinian’s own compilation, on which Napoleon pushes down in the relief. Indeed, it should be recalled that Justinian himself had ordered the compilation of those Roman law materials deemed worthy of conservation, and the destruction of the rest, for reasons quite similar to the simplifying impulse that the relief attributes to Napoleon. That Justinian went so far as to destroy the discarded Roman law materials, while it remains possible to consult the works of Domat and Pothier, among others, in fact suggests that Justinian’s codification efforts were in one sense at least more radical than Napoleon’s.

The idea that the Civil Code stands at least in partial continuity with the ius commune, and with the broader civil law inherited from Rome, can also be discerned quite readily from the Code itself. As is well known, the bulk of the Code’s provisions can be traced directly to the work of Domat and especially Pothier, whose principal contributions were in the form of commentaries on the ius commune and French customary law. A perhaps particularly well-known example in which the codifiers conserved the prior law can be found in a provision allowing for rescission of a contract for the sale of land where the seller has been paid less than seven twelfths of its market value – a customary gloss that had been put on the ius commune’s doctrine of laesio enormis. The exceptional nature of this provision, as against the then-ascendant ideas of liberal individualism and attendant voluntaristic conception of contract, have long been recognized. In fact, it is said to have been initially rejected by the three-party committee charged with drafting the Code, and that Napoleon’s personal intervention on that committee (as its effective fourth member) ultimately accounts for its inclusion in the final enacted version of the Code.

Finally, continuity with the spirit of the ius commune, in addition to its letter, can be found in the famous Discours préliminaire drafted by the Code’s chief architect, Jean-Étienne-Marie Portalis, and pronounced upon the presentation of the Code’s first draft in 1801. There is much in the Discours that is entirely consistent with the natural law foundations on which the ius commune was said to rest. Perhaps most notable are its endorsement of the necessity of positive law to complete natural justice (disputes otherwise being interminable), and the parallel necessity of calling upon “equity”, conceived of as a “return to the natural law”, to interpret the law where its precise application is unclear. Both ideas are entirely at home in the work of the Ancien régime jurists. But more than that, the idea of “equity” in particular eventually lead to the concession, at the end of the nineteenth century, that the Code had not served to displace those parts of the old law that had not been expressly incorporated within it. This occurred, for instance, with respect to the recognition of unjustified enrichment as a stand-alone source of obligation, which had not been expressly included in the Code as enacted in 1804.

As against these indicia of continuity, rejoinders can be offered on both fronts. In respect of the substance of the Code, its essentially liberal premises have been stressed by many commentators, both favourable and unfavourable to the premises in question. To be sure, much of the work of transmuting the ius commune into rules and principles compatible with philosophical liberalism had already been completed by others, including most notably by Pothier. But the Code went further still, for instance by affirming a nigh-absolute conception of ownership over the ius commune’s more feudal inclinations. It also recast the rights and duties of persons subject to the civil law in the fully abstract, individualist language of subjective rights. Thus, for example, article 7 of the Code as enacted provided that all persons, citizens or not, are entitled to exercise their civil rights – a provision made entirely in the abstract, without referencing the particular legal relationships from which the rights and duties at issue proceed. Even family relationships, discussed extensively in the Code, were framed in terms of individual rights and duties borne in the abstract.

The most important rejoinder, however, pertains to the spirit of the Code. True, it was eventually admitted, at the end of the nineteenth century, that the Code had not served to displace all of the prior law that it had not expressly affirmed. Nonetheless, the codification movement begun with the French Civil Code of 1804 operated an important shift in the way that jurists conceived of the ultimate source of the civil law. That there is a French Civil Code entirely distinct from the German one, or for that matter from the various Codes such as those of the American state of Louisiana and the Canadian province of Quebec, implies a profound shift in legal thought that had no real parallels prior to the nineteenth century, and indeed may have no real parallel even today in those jurisdictions that have not participated in the codification process. While lawyers whose intellectual heritage lies in the European ius commune continue to interact with each other and exchange ideas, they do so while under the assumption that their legal systems are ultimately distinct from each other, albeit influenced by similar historical sources that may point to shared avenues for future development. They certainly do not do so while under the assumption that they participate in a singular legal culture.

The true import of this shift is brought to the fore by the preliminary provision of the Civil Code of Québec, which replaced Quebec’s original Civil Code, largely based on the French Code of 1804, in 1994. To quote that provision at length:

The Civil Code comprises a body of rules which, in all matters within the letter, spirit or object of its provisions, lays down the jus commune, expressly or by implication. In these matters, the Code is the foundation of all other laws, although other laws may complement the Code or make exceptions to it.

This, then, is the ultimate consequence of the movement begun by the French Civil Code enacted under Napoleon in 1804, and perhaps the strongest argument in favour of its (at best) ambiguous relationship with the tradition of the ius commune. Rather than providing a particular embodiment of that tradition, the codification itself has taken on the status of ius commune for the individual jurisdictions that have followed in France’s footsteps. This shift is reflected in a manner of teaching in most civilian law schools, which now focus almost exclusively on the national law, including in private law topics historically most associated with the Roman law and the ius commune. It also offers a contrast with the still largely uncodified English common law tradition, which, outside of the United States at least, is still often understood as a unitary body of law subject to local variation – which is to say, in terms that would have been readily understood by authors working in the tradition of the ius commune.