Bartolomé de Las Casas, the Inter-American Court, and Natural Law

An Introduction to Natural Law at the Inter-American Court

The New Digest is pleased to feature this guest essay from Mr. Ignacio Boulin. Ignacio is a lawyer from Universidad de Mendoza, and holds a Master's in Administrative Law from Universidad Austral and an LL.M. from Harvard Law School. He is a PhD candidate at KU Leuven, focusing on the intersection of administrative law and international human rights law in the Inter-American Court of Human Rights.

He is a professor at Universidad Nacional de Cuyo and Universidad Austral. He litigates human rights cases before various international courts. He has published the books Decisiones Razonables. Hacia el uso del principio de razonabilidad en la motivación administrativa and Derecho Constitucional y Políticas Públicas (co-authored with Alfonso Santiago), as well as several articles on Human Rights, Constitutional Law, and Administrative Law.

The current understanding of human rights law in the Inter-American system is deeply entrenched with what can be labeled as the Latin-American approach to human rights. Latin America’s history, its elites’ education, the role of Catholicism in the hearts and minds of its people, the relationship between the colony and the empire, the reception of Enlightenment ideas, all these aspects shaped Latin American human rights culture. The Inter-American Human Rights system is a product of that culture.

History’s protagonists might not have a clear conscience of their influence in the future, nor might they be aware of the influx that other people have in them. However, “[n]o man is an island entire of itself”[1]. Personal ideas and personal projects replicate over time and engender culture[2]. One of the most relevant figures in Latin America, and for sure the first one, is Bartolomé de las Casas.

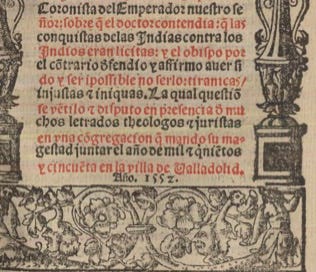

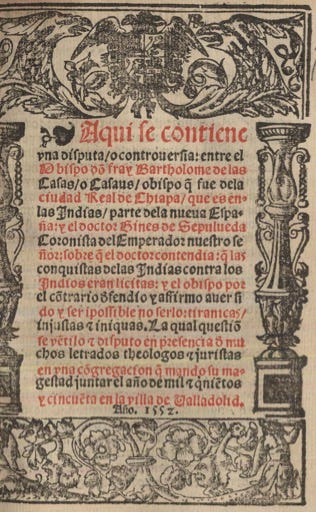

Born in Seville, Spain, in 1484 or 1485[3], the Dominican friar Bartolomé de las Casas has been called the “founder of human rights.”[4] A passionate man and an adventurer, he was one of the many who followed the route Columbus had opened in 1492 and sailed to the “Indies” in 1502 for the first time.[5] Ordained as a priest between 1506 and 1509,[6] he himself was a slave owner.[7] After some Dominican friars opened his eyes regarding the ill-treatment of Spanish colonizers to indigenous peoples, de las Casas converted into their most fervent defender.[8]

Bartolomé de las Casas was more of an advocate and activist than a scholar.[9] His main goal was not to develop a theoretical contribution to the law but to improve the living conditions of native Americans (this goal-oriented approach to law probably improved his creativity). His use of the principles of natural law and his imaginative approach to Roman law and canon law developed in the medieval ages (the medieval ius commune)[10] make him a remarkably influential jurist in the centuries to come.

Las Casas approached to law to tackle the problem he saw before his eyes: protecting native Americans. Thus, his “essential achievement […] was to graft, quite consciously, a juridical doctrine of natural rights onto Aquinas’ teaching on natural law.”[11] Indians had “rights” that did not depend on any positive law but on the mere fact of their membership in the human family.[12] In such a manner, native people of the Americas and Europeans were equal in their dignity. He wrote: “[a]ll the races of the world are men, and of all men and of each individual there is but one definition, and this is that they are rational. All have understanding and will and free choice, as all are made in the image and likeness of God.”[13]

Bartolomé de las Casas was also a creative interpreter of the medieval legal theory.[14] For example, his defense of the “dominium” of the Indians over their land was based on the maxim “Quod omnes tangit debet ab omnibus approbari” (what touches all must be approved by all) proved his deep knowledge of the law, as well as his originality in construing it.[15] The quoted Roman principle was used in canon law to limit the power of the Pope, who should respect the hearing rights of the lesser members of the church hierarchy.[16] From this principle it could be deduced that “the pope cannot give the infidels a new king without their consent.” [17] Bartolomé de Las Casas used it to argue that the Pope could not grant the Spanish king dominium over the New World “without the consent of the native peoples.”[18] Las Casas used this maxim imaginatively to overcome the new situation’s challenges.

Las Casa was a prolific writer, and with his intuitions he fostered the foundations of the human rights discourse and international law in the Americas. For this post’s purposes, I would like to briefly highlight just three main concepts he developed that, in my opinion, are at the basis of the Latin American approach to human rights: natural law, solidarity, and the social role of authority.[19]

Natural law. De las Casas understood natural law as “the set of laws that constitute rights and duties relating to the same human nature; since it arises from the same human nature, it belongs to all men without distinction.”[20] The friar argued that no human arrangement could erase the human dignity of the American natives, as this belonged to a higher level than the monarchs’ enacted laws. This stronghold of natural law, even against positive law, would be seen in the region's future understanding of international law.

Authority. Social authority is another relevant notion for de las Casas, the influence of which can still be found in the Latin American approach to human rights law. Drawing on Aristotle, he noted that sociability arises from human nature: man is naturally sociable.[21] People come together in communities due to inherent instincts, impulses, and natural desires, in addition to rational considerations. This is why de las Casas references the entitlement of indigenous populations to establish their own cities and kingdoms.[22] Alongside a community arises the need for a governing authority, as the absence of leadership jeopardizes the survival of a state.[23] Authority in Las Casas has a relevant role and is closely related to the common good.

Solidarity. A third concept related to De las Casas opus is solidarity. Solidarity is a concept the meaning of which seems easier to see in practice than to define.[24] Rüdiger Wolfrum appreciates solidarity in an international legal order based on cooperation instead of mere coordination.[25] And its relevance to human rights has been deeply discussed.[26] Present times are abundant in solidarity mantras, and it is considered as a principle of international law.[27] Yet Bartolomé De Las Casas lived and worked before Grotius, Puffendorf, or the French solidarists Durkheim and Duguit.[28] It has been said that also Francisco de Vitoria, contemporary to De Las Casas, had a solidarity intuition saw a world order based on Christian Values.[29]

In the writing of Bartolomé De Las Casas, I believe solidarity manifests in his approach to native Americans, the discovered lands and their resources. The new world and its inhabitants are not for depletion. A non-individualistic approach to society and rights arises in Las Casas. He understands that “[e]ven though reason shows us that all social life is directed towards that common good, our own selfishness inclines us to seek only individual good, leading each person to pursue their own interests. In this way, if there is no one entrusted with directing everyone towards the common good, each person would seek only their particular good, and the state of that society would be calamitous.”[30] This is related to what 350 years later, the Chilean international scholar Alejandro Álvarez would invoke through the concept of solidarity, “characterized less by a definitive agenda than by a general aversion to the absolutism of individual rights and an emotional preference for social responsibility.”[31]

These three characteristically “las-Casasians” features can be found in Latin American human rights thinking in the decades of the 20th century when international human rights law was being crafted. The natural law foundations, rooted in las Casas’ creativity, are related to what can be framed, for good or bad, as the Latin American detachment from the limits of positive law. The positive boundaries of law can be stepped over if the goals are worthy to achieve, as it will be explained below.

Las Casas' view of the state’s authority, not as an enemy to reject but as an ally for fulfilling rights, is central in the Latin American approach to rights. The authority must pursue the common good, and it is for that precise reason it can rule.[32]

Finally, the solidarity mindset was instrumental in allowing the Latin American bloc of states to find a middle way when the USA and the Soviet blocs were trapped in discussion over the Universal Declaration on Human Rights, arguing for a more individual or collective approach to rights. The Latin American common ground was neither individualistic nor collective but a solidary view on rights and society.[33]

Las Casas influence in the Inter-American System

History does not dictate the course of the future, although what it was impacts what it is and what it will be. In what follows, I briefly argue that the arc of international human rights law in Latin America shows several continuities from Las Casas until today. If the observer adopts a distant perspective, it will discern the influence of the human rights tradition on the Inter-American Court's approach to international law and its own role. His reliance on natural law, solidarity, and the social role of authority helped establish a tradition that embeds the Inter-American Court’s decisions.

A short introduction to the Inter-American Court. The Inter-American Court of Human Rights was established in 1978 when the American Convention on Human Rights entered into force. This represented a benchmark in the history of the Inter-American System, as the Court was designed to issue binding decisions that states undertook to fulfil in all cases to which they are parties.[34]

The Court has seven members. It’s role starts after the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights has issued a report declaring a state party to the American Convention has violated a human right, and making a recommendation to repair. If the state does not follow the recommendation, the Commission will subsequently present the case before the Court[35] to obtain a binding decision.[36] The procedure before the Court is a judicial one in which the state is the defendant, and the Commission—not the victim—is the main plaintiff,[37] as only the Commission can bring the case before the Court.

Natural law in the Inter-American Court

International law is considered primarily consensual, as, in principle, it only binds states if they provide their consent to be bound.[38] This classical position faces several challenges when dealing with human rights,[39] especially within the Inter-American Court. To understand this it is needed to focus briefly on the sources of international law.

Article 38 of the Statute of the International Court of Justice is usually recognized for gathering the sources of international law.[40] This provision identifies the following sources:

a. “international conventions, whether general or particular, establishing rules expressly recognized by the contesting states;

b. international custom, as evidence of a general practice accepted as law;

c. the general principles of law recognized by civilized nations;

d. […] judicial decisions and the teachings of the most highly qualified publicists of the various nations, as subsidiary means for the determination of rules of law.”[41]

However, the traditional sources of international law are being disrupted by new inputs of international origin that do not fit into the categories of treaties, customary law, or general principles. This is not a critical evaluation but rather a mere description of the phenomenon. As a result of pluralism and fragmentation, international law is experiencing a process of informalization in which there is a specific rejection of formal indicators for determining rules of international law.[42]

Natural law enters here. In tragic cases, the Court understanding of the interplay between the law, rights, and states’ obligations,[43] seems to reject unfair outcome for a victim if it can be avoided resorting to the principles of natural law, as “natural law must always prevail over positive law.” [44]

Natural law emerges as a potential way to escape from unjust results in the concrete cases the Inter-American Court deals with. Then, for example, this intellectual tactic—as it might be called—is valid to extend the effects of law, even against the state’s consent, as the Court did in the case of Almonacid Arellano v. Chile.

This case relates to the state failure to investigate and sanction those responsible for the extrajudicial execution of Luis Alfredo Almonacid Arellano, a school teacher and communist party supporter. He was detained and shot dead on September 16, 1973, in front of his family, under a generalized repression after Pinochet’s coup. In 1978 the military dictatorship adopted Decree-Law 2191 that granted amnesty “to all individuals who performed illegal acts, whether as perpetrators, accomplices or accessories after the fact, during the state of siege in force from September 11, 1973, to March 10, 1978, provided they are not currently subject to legal proceedings or have been already sentenced”.[45]

The Chilean defense argued that the Court had no ratione temporis competence, as it had recognized the jurisdiction of the Court in 1990 only for events which had occurred after the ratification instrument had been deposited.[46] It was also discussed whether a statute of limitations was applicable to this crime.[47]

In its judgement, the Court considered that the state cannot invoke a statute of limitations to avoid prosecuting the crime, as that would collide with the Convention on the Non-Applicability of Statutory Limitations to War Crimes and Crimes Against Humanity.[48] However, Chile had not ratified the said Convention.[49] Still, the Court considered that Chile was bound even when there was no positive law to oblige it:

Even though the Chilean State has not ratified said Convention, the Court believes that the non-applicability of statutes of limitations to crimes against humanity is a norm of General International Law (ius cogens), which is not created by said Convention, but it is acknowledged by it. Hence, the Chilean State must comply with this imperative rule.[50]

Up to date, Chile has not ratified the Convention, which only has 56 parties.[51]

Natural law allowed Bartolomé de las Casas to defend the rights of Native Americans not to be ruled by foreign empires. The Inter-American Court, with members more subtle and others not so, has integrated natural law into its case law.

The Court’s dilemma with state authority

David Kennedy has argued that it is somehow paradoxical that the human rights movement finds its main antagonist in the state while at the same time it tries to oblige the state to provide the solutions to the violations it perpetrates:

Although human rights advocates express relentless suspicion of the state, human rights places the state at the center of the emancipatory process, structuring liberation as a relationship between an individual right holder and the state.[52]

For Kennedy, there is a sort of contradiction: “To be free is . . . to have an appropriately organized state”.[53] But what Kennedy sees as a problem, the Latin American tradition, embedded in the classical approach to law and society, considers the proper order of things. Liberty requires a state that provides the common good where to exercise that liberty. [54]

Aristotle suggested that human beings naturally form communities.[55] When communities are complex enough, there is a need for a fair exercise of authority to secure the common good.[56] This exercise of authority is a positive characteristic of the state[57] that also arises from human nature.[58] Authority and freedom, in the classical comprehension of society, might present tensions but can be harmonized. Bartolomé de las Casas shared this view. There is a need for the state authority to “direct (…) everyone towards the common good.”[59] Freedom is only possible in a well-ordered community. In such a way, what for Kennedy is problematic, for Aristotle and Las Casas was the proper order.

The Inter-American Court has remained in line with the Latin American international law idiosyncrasy regarding the state’s role as common good provider[60] and as guarantor and protector of human rights.[61] It is something well based in the American Convention, where the state is responsible for securing and guaranteeing rights in a vast proportion, as it appears in articles 1.1 and 2 of the Convention. The state parties “undertake to respect the rights and freedoms recognized” (article 1.1) and “to adopt, in accordance with their constitutional processes and the provisions of this Convention, such legislative or other measures as may be necessary to give effect to those rights or freedoms” (article 2).

It should not be a surprise that the Court considers the state at the center of the system. It is the State, and no other subject, who has an international obligation to respect and guarantee rights –from the violations that can be caused by the state’s agents or private subjects. Regarding positive obligations, it is the state who has to secure rights. Human rights law will be used to compel the state to fulfil its responsibility if it fails to do so.

The case of Martina Vera Rojas is paradigmatic to support this observation. Martina Vera Rojas is a young Chilean girl born in 2006 who faces various disabilities caused by an uncommon, incurable, and progressive neurological condition called Leigh Syndrome.[62] Her condition led to a substantial decline in her cognitive abilities and motor skills, needing constant and comprehensive in-home healthcare. Initially, Martina’s parents' private health insurance, Isapre MasVida, funded her medical care.[63]

During the girl’s first three years of life, the private insurance company covered the costs of home care, but in the fourth year, it declined to continue doing it. Isapre MasVida unexpectedly terminated her coverage for catastrophic illnesses, transferring to her parents the significant financial burden of her treatment. This decision by Isapre was legal under a regulation of the Chilean Health Superintendency, which granted private insurers the discretionary authority to end coverage for catastrophic illnesses solely based on the duration of the illness, without any obligation to assess the patient’s health condition and requirements.[64] Martina’s parents exhausted domestic remedies without any positive results, as the Chilean Supreme Court considered that the private company's decision was according to the law.[65]

When the case arrived at the Inter-American system, it was for the Court to decide whether “the State fulfilled its obligation to respect and ensure the rights to life, dignity, personal integrity, rights of the child, health, and social security, in conjunction with the obligation to ensure rights without discrimination and the duty to adopt domestic legal provisions, with respect to the decision of Isapre MasVida to discontinue the benefit of home hospitalization for Martina Vera Rojas.”[66]

The Court considered that besides Article 1 (1) state’s duty “to respect the rights and freedoms”[67] the state also has the obligation of ensuring rights. This requires states to “to organize the governmental apparatus and, in general, all the structures through which public power is exercised, so that they are capable of juridically ensuring the free and full enjoyment of human rights.”[68] And health, as a public good, depends on the state who has to exercise its authority to secure private parties act according to human rights.

With regard to the impacts on rights of third-party actions in health service provision, this Court has established that, given that health is a public good whose protection is the State’s responsibility, the State has an obligation to prevent third parties from unduly interfering in the exercise of the rights to life and personal integrity, which are particularly vulnerable when someone is receiving health care.[69]

The Court supported a vigorous exercise of authority to ensure rights, requesting the state to force private companies through regulation. There is no place for a weak state, nor for private behaviour against solidarity. For the Court, states must “regulate companies so that their actions respect the human rights recognized in the different instruments of the inter-American system”.[70] The Court enters well into the dominion of domestic regulation with a clear message: states must exercise their authority to secure rights, as at the end of the day the right to health depends on the state.

Solidarity and common good

The role of the public authority –the government—is noticeable in the Latin American human rights culture. Contrary to the British liberal tradition of limiting the government[71],the Latin American tradition maximizes the role of the government. There is no defensive position but an ideal cooperative situation between the public authority, individuals, and groups in the quest for a common good that includes rights.[72] This entails risks that I cannot develop here. But it also can provide some benefits.

In the Inter-American Court case law, the role of the government is vital to establish a just social order, that conciliates human rights with the common good, defined by the Inter-American Court as “the conditions of social life that allow the members of society to reach their greatest level of personal development and the greatest validity of democratic values”.[73] This idea resembles some features of solidarity, in which authority limits individual rights to secure the common good.

Solidarity originates from a Latin legal phrase, “in solidum”, which refers to a well-known legal concept denoting “a legal relationship [...] jointly undertaken by a group, and from which every member of the group is accountable for the entirety”.[74] Solidarity refers to an obligation that causes all debtors, even individually, to be held accountable for the whole debt. This implies that all individuals are responsible for it, as each one bears responsibility for the entire debt.[75]

The translation of the idea of solidarity into human rights law within the Inter-American system can also be associated with a soft understanding of law as a system.

In its approach, the Court seems to acknowledge that the rigid application of the law could lead to outcomes contrary to the values of justice and solidarity that the American Convention seeks to promote. Instead of merely mechanically adhering to positive law, the Court can consider the underlying principles of solidarity and the pursuit of fairness in its decision.

This notion might appear risky from a systemic perspective, as it could potentially undermine the coherence and predictability of the legal system,[76] especially when, under the absence of a regional legislator, the Court can “fill in the interstices of international law and […] resolve the uncertainties.”[77] It can also give too much power to the Court.

Some final observations

The Court’s reliance on principles of dignity, solidarity, and the common good demonstrates a continuity with Latin America’s historical and philosophical traditions. However, this approach also raises concerns about the predictability and coherence of international law. If “corruptio optimi pessima”, the wrong use of natural law can be invoked to override or expand positive law, or to enlarge judicial power at the expenses of the people.

The influence of natural law in the Inter-American Court’s jurisprudence seems undeniable. How to move forward is the question.

[1] Donne, J., Devotions Upon Emergent Occasions; Together with Death’s Duel. Meditation XVII, 5th ed., 1638, available at https://www.proquest.com/docview/2240902626?accountid=17215&parentSessionId=4%2FL%2FGxWP3uIMXayOjA0x7lo%2FOxnuQRFa34n%2FlgsvlpU%3D&pq-origsite=primo&imgSeq=1.

[2] See,J. M. Keynes, The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money, 1, Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2018. Keynes wrote: “the ideas of economists and political philosophers, both when they are right and when they are wrong, are more powerful than is commonly understood. Indeed the world is ruled by little else. Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influences, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist. Madmen in authority, who hear voices in the air, are distilling their frenzy from some academic scribbler of a few years back. I am sure that the power of vested interests is vastly exaggerated compared with the gradual encroachment of ideas. Not, indeed, immediately, but after a certain interval; for in the field of economic and political philosophy there are not many who are influenced by new theories after they are twenty- five or thirty years of age, so that the ideas which civil servants and politicians and even agitators apply to current events are not likely to be the newest. But, soon or late, it is ideas, not vested interests, which are dangerous for good or evil”. P. 340.

[3]K. Pennington, «Bartolomé de Las Casas», en Rafael Domingo, Javier Martínez-Torrón (eds.) Great Christian Jurists in Spanish History, 1, Cambridge University Press, 2018, p. 98, fecha de consulta 10 septiembre 2023, en https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/identifier/9781108624732%23CN-bp-5/type/book_part. Citar acá a Gustavo Gutierrez

[4] See Las Casas Institute, About the Las Casas Institute, in the in which is recalled that Professor Conor Gearty of the London School of Economics called him as the “founder” of human rights. https://www.bfriars.ox.ac.uk/research/las-casas-institute-for-social-justice/about-the-las-casas-institute/bartolome-de-las-casas/ . Las Casas might have been the first one to use the term human rights when providing conclusions on why the Spaniards had a “bad conscience” for slaving Indians: “Following the rules of human rights that are established through reason and natural law...sometimes decisions and things are permitted or justified for certain reasons, which, when these reasons cease, can no longer be tolerated (…). Obras completas, vol. 10, 232–33. 44 Ibid., 236. See at. https://books.google.com.pe/books?id=Kxh7eUWilWwC&pg=PA104&lpg=PA104&dq=%22según+las+reglas+de+los+derechos+humanos,+confirmados+por+la+razón+y+ley+natural%22&source=bl&ots=EzrnLEe7Bn&sig=ACfU3U0l6dsi3o_LLZ6ofGmiKtTjUzXfEg&hl=es&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwifrpLhvLSBAxXuGLkGHQzZCR4Q6AF6BAgbEAM#v=onepage&q=%22según%20las%20reglas%20de%20los%20derechos%20humanos%2C%20confirmados%20por%20la%20razón%20y%20ley%20natural%22&f=false

[5] K. Pennington, «Bartolomé de Las Casas», cit., p. 99.

[6] K. Pennington, «Bartolomé de Las Casas», cit.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid., p. 99. According to Pennington, “His condemnations of the brutality and greed of Spanish conquistadors angered the powerful in the church and the state during the sixteenth century”. See, p. 98

[9] P. Carozza, «From conquest to constitutions: retrieving a Latin American tradition of the idea of human rights», cit. Carozza considers Bartolomé de Las Casas a legal innovator: “First, Las Casas consistently framed the requirements of justice in terms of the rights of the Indians. We should not undervalue the importance and novelty of this simply because that way of talking is so familiar to us moderns. While Las Casas' thought is clearly in the same Thomist tradition as his Dominican brothers of Salamanca he uses a language of subjective natural rights that was not found in Aquinas' work itself.

[10] He had a sophisticated understanding of the jurisprudence of Roman and canon law developed in the middle ages. Pennington, K. Pennington, «Bartolomé de Las Casas», cit., p. 99.

[11] Brian. Tierney, The idea of natural rights: studies on natural rights, natural law and church law 1150 - 1625., Scholars Press, Atlanta, 1997. P. 276.

[12] Of course, his understanding of rights had a clear catholic root. “They are our brothers, and Christ gave His life for them”. See, Ibid., p. 273.

[13] P. Carozza, «From conquest to constitutions: retrieving a Latin American tradition of the idea of human rights», cit.

[14] K. Pennington, «Bartolomé de Las Casas», cit., p. 100.

[15] Ibid., p. 103.

[16] Ibid., p. 106.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid.

[19] P. Carozza, «From conquest to constitutions: retrieving a Latin American tradition of the idea of human rights», cit.

[20] The Spanish original reads: “como el conjunto de leyes que constituyen derechos y deberes relativos a la misma naturaleza humana. Ya que surge de la misma naturaleza humana, pertenece a todos los hombres sin distinción. See at Bartolomé de las Casas, Tratado Comprobatorio, México, 1965, II, p. 1069, quoted in M. Beuchot, «La aplicación del derecho natural a los indios, según Bartolomé de las Casas. De la teología académica a la profética.», en Evangelización y teología en América (siglo XVI), UNAV, 1990, p. 1111.

[21] Cfr. V. M. S. Zorrilla, «El estado de naturaleza en Bartolomé de las Casas», 2009, p. 35, fecha de consulta en https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:190804752.

[22] Cfr. K. Pennington, «Bartolomé de Las Casas», cit., p. 103.

[23] Ibid., p. 106.

[24] K. Gorobets, «Solidarity as a Practical Reason: Grounding the Authority of International Law», Netherlands International Law Review, vol. 69, 1, 2022, p. 4.

[25] R. Wolfrum, «Solidarity», en Dinah Shelton (ed.) The Oxford Handbook of International Human Rights Law, 1, Oxford University Press, 2013, p. 402, fecha de consulta 25 octubre 2023, en https://academic.oup.com/edited-volume/42626/chapter/358048013.

[26] K. Gorobets, «Solidarity as a Practical Reason», cit.; C. Wellman, «Solidarity, the Individual and Human Rights», Human Rights Quarterly, vol. 22, 3, 2000.

[27] K. Gorobets, «Solidarity as a Practical Reason», cit., p. 4. R. Wolfrum, «Solidarity», cit.

[28] See, K. Gorobets, «Solidarity as a Practical Reason», cit., p. 6. Also M. Koskenniemi, The Gentle Civilizer of Nations: The Rise and Fall of International Law 1870–1960, 1, Cambridge University Press, 2001, p. 266, fecha de consulta 17 septiembre 2023, en https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/identifier/9780511494222/type/book.

[29] V. Marotta Rangel, «The Solidarity Principle, Francisco de Vitoria and the Protection of Indigenous Peoples», en Holger P. Hestermeyer y otros (eds.) Coexistence, Cooperation and Solidarity (2 vols.): Liber Amicorum Rüdiger Wolfrum, Brill | Nijhoff, 2012, p. 132, fecha de consulta 25 octubre 2023, en https://brill.com/view/title/19155.

[30] M. Beuchot, «La aplicación del derecho natural a los indios, según Bartolomé de las Casas. De la teología académica a la profética.», cit.

[31] M. Koskenniemi, The Gentle Civilizer of Nations, cit., p. 289.

[32] Aquinas defines law as “an ordinance of reason for the common good, made by him who has care of the community, and promulgated”. T. Aquinas, Summa Theologica, I-I, q. 90, art. 4, fecha de consulta 1 octubre 2023, en https://www.ccel.org/ccel/aquinas/summa.FS_Q90_A4.html.

[33] Cfr. M. A. Glendon, «The Forgotten Crucible: The Latin American Influence on the Universal Human Rights Idea», cit., p. 37. In general, see also M. A. Glendon, Rights talk: the impoverishment of political discourse, Freepress, New York, 1991.

[34] American Convention, art. 68.

[35] Under art. 45 of the 2013 Rules of Procedure, the Commission will present the art. 51 report by default—this is, it will refer the case to the Court unless by a reasoned decision it decides not to do so. See http://www.oas.org/en/iachr/mandate/Basics/rulesiachr.asp (last visited on Mar. 13, 2014).

[36] American Convention, art. 61. The Inter-American Court, interpreting article 61, stated that a government cannot waive the fulfilment of the regular procedures set forth in article 61 of the American Convention. See Viviana Gallardo v. Gov't of Costa Rica, Inter-Am. Ct. H.R. (ser. A) No. 101, ¶ 12-25 (Nov. 13, 1982), available at http://www.corteidh.or.cr/docs/opiniones/seriea_101_81_ing.pdf .

[37] Inter-Am. Comm. H.R., Rules of procedure, supra note 27, art. 45.

[38] See on this, in general, G. Hernández, International Law, 1, Oxford University Press, 2019, p. 32, fecha de consulta 10 agosto 2023, en https://www.oxfordlawtrove.com/view/10.1093/he/9780198748830.001.0001/he-9780198748830.

[39] B. Simma; P. Alston, «The Sources of Human Rights Law : Custom, Jus Cogens, and General Principles», The Australian Year Book of International Law Online, vol. 12, 1, 1992. See, as well, ICJ Rep 1966, dissenting opinion of Judge Tanaka, p.4 at 298.

[40] G. Hernández, International Law, cit., p. 33.

[41] 59 Stat.. 1055, T.S. 993, Art. 38(1).

[42] Cfr., J. D’Aspremont, «The politics of deformalization in international law», Goettingen Journal of International Law, 2011, Institut für Völker- und Europarecht, p. 510, fecha de consulta 11 octubre 2023, en http://gojil.uni-goettingen.de/ojs/index.php/gojil/article/view/194..

[43] See, concurring opinion of Judge Cancado in IACtHR, Advisory Opinion OC-17/2002, of August 28, 2002, requested by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, Juridical Condition and Human Rights of the Child, Series A No 17, párr. 20. Footnote 153: J. Maritain, O Homem e o Estado, 4th. ed., Rio de Janeiro, Ed. Agir, 1966, p. 84, and cf. pp. 97-98 y 102; A. Truyol y Serra, "Théorie du Droit international public - Cours général", 183 Recueil des Cours de l'Académie de Droit International de La Haye (1981) pp. 142-143; L. Le Fur, "La théorie du droit naturel depuis le XVIIe. siècle et la doctrine moderne, 18 Recueil des Cours de l'Académie de Droit International de La Haye (1927) pp. 297-399; C.J. Friedrich, Perspectiva Histórica da Filosofia do Direito, Rio de Janeiro, Zahar Ed., 1965, pp. 196-197, 200-201 and 207; J. Puente Egido, "Natural Law", in Encyclopedia of Public International Law (ed. R. Bernhardt/Max Planck Institute), vol. 7, Amsterdam, North-Holland, 1984, pp. 344- 349. - And, for a general study, cf. A.P. d'Entrèves, Natural Law, London, Hutchinson Univ. Libr., 1970 [reprint], pp. 13-203; Y.R. Simon, The Tradition of Natural Law - A Philosopher's Reflections (ed. V. Kuic), N.Y., Fordham Univ. Press, 2000 [reprint], pp. 3-189. The law cannot limit states’ duties if natural law requires its involvement. An example of this approach is the influential brasilian scholar and international judge, Antonio Cancado Trindade, who wrote a concurring opinion in the Advisory Opinion on the Legal Condition of the Child, declaring: The “eternal return” or “rebirth” of jusnaturalism has been reckoned by the jusinternationalists themselves, much contributing to the assertion and the consolidation of the primacy, in the order of values, of the State obligations as to human rights, and of the recognition of their necessary compliance vis-à-vis the international community as a whole. This latter, witnessing the moralization of law itself, assumes the vindication of common superior interests. One has gradually turned to conceive a truly universal legal system [quotations omitted].

[44] Idem, footnote 154, citing, G. Radbruch, Filosofia do Direito, vol. I, Coimbra, A. Amado Ed., 1961, p. 70.

[45] ACtHR, Case of Almonacid Arellano et al. v. Chile. Preliminary Objections, Merits, Reparations and Costs. Judgment of September 26, 2006. Series C No. 154, para. 99. 92 Ibid., at para. 82(10).

[46]ACtHR, Case of Almonacid Arellano et al. v. Chile. Preliminary Objections, Merits, Reparations and Costs. Judgment of September 26, 2006. Series C No. 154, para. 39.

[47] ACtHR, Case of Almonacid Arellano et al. v. Chile. Preliminary Objections, Merits, Reparations and Costs. Judgment of September 26, 2006. Series C No. 154, para. 72, 84, 152.

[48] ACtHR, Case of Almonacid Arellano et al. v. Chile. Preliminary Objections, Merits, Reparations and Costs. Judgment of September 26, 2006. Series C No. 154, para. 153.

[49] United Nations, Treaty Series , vol. 754, p. 73.

[50] ACtHR, Case of Almonacid Arellano et al. v. Chile. Preliminary Objections, Merits, Reparations and Costs. Judgment of September 26, 2006. Series C No. 154, para. 99. 92 Ibid., at para. 153.

[51] Convention on the non-applicability of statutory limitations to war crimes and crimes against humanity. Adopted by the General Assembly of the United Nations on 26 November 1968, https://treaties.un.org/pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=IND&mtdsg_no=IV-6&chapter=4&clang=_en#1

[52] D. Kennedy, The Dark Sides of Virtue: Reassessing International Humanitarianism, Princeton University Press, Princeton, 2004, p. 16, fecha de consulta 29 mayo 2022, en http://www.degruyter.com/view/books/9781400840731/9781400840731/9781400840731.xml.

[53] Ibid.

[54] See, Aristotle, Politics, p. 3, fecha de consulta en https://historyofeconomicthought.mcmaster.ca/aristotle/Politics.pdf. V. H. Basterretche, «Independencia, autoridad y bien común», en Semana Tomista: justicia y Misericordia, Buenos Aires, 2016, fecha de consulta en http://bibliotecadigital.uca.edu.ar/repositorio/ponencias/independencia-autoridad-bien-comun.pdf.

[55] Aristotle, Politics, cit. p. 6.

[56] See, Ibid., p. 3. V. H. Basterretche, «Independencia, autoridad y bien común», cit.

[57] Aristotle, Politics, cit., 157.

[58] See, M. P. Cavedon, «Early stirrings of modern liberty in the thought of St. Thomas Aquinas», Politics and Religion, 2023, p. 3.

[59] M. Beuchot, «La aplicación del derecho natural a los indios, según Bartolomé de las Casas. De la teología académica a la profética.», cit.

[60] IACtHR, Compulsory Membership in an Association Prescribed by Law for the Practice of Journalism, November 13, 1986, Serie A, 05.

[61] F. Aravena, «Hernán Santa Cruz: un diplomático esencial para la creación de la Declaración Universal de Derechos Humano», Anuario de Derechos Humanos, vol. 17, 2, 2021, p. 288.

[62] IACtHR, Caso Vera Rojas y otros v. Chile, Judgement of October 1, 2021, Preliminary Exceptions, Merits, Reparations and Costs, Series C 439, par. 51.

[63] Idem, par. 52. Isapres are “Instituciones de Salud Previsional”, a private system of health insurance. See, https://www.supersalud.gob.cl/664/w3-article-2528.html .

[64] IACtHR, Caso Vera Rojas y otros v. Chile, Judgement of October 1, 2021, Preliminary Exceptions, Merits, Reparations and Costs, Series C 439, par. 53.

[65] Idem, par. 57, 58.

[66] Idem, par. 72.

[67] Idem, par. 81.

[68] Idem, par. 82.

[69] Idem, 89.

[70] Idem par. 85.

[71] See, p. 7. For example, Bentham and his advise to the government on economic matters: Be quiet. See, J. E. Crimmins, «Jeremy Bentham», The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. See, also, A. Vermeule, Common good constitutionalism, Polity Press, Medford, 2022, p. 7.

[72] This visión has a strong catholic roots. For Thomas Aquinas, common good is the goal of society, and all the laws are ordered towards common good, and the authority leads towards common good. See, Summa Theologica, I-II, q. 90, a. 2; also, I, q. 105, a. 2.

[73] IACHR, Advisory Opinion OC-6/86. The word «Laws» in article 30 of the American Convention on Human Rights, 1986. Parr. 66.

[75] G. Amengual, Antropología filosófica, Biblioteca de Autores Cristianos, Madrid, 2007, p. 377.

[76] On this, see G. I. Hernández, «Sources and the Systematicity of International Law: A Co-Constitutive Relationship?», en Samantha Besson, Jean d’Aspremont (eds.) The Oxford Handbook of the Sources of International Law, 1, Oxford University Press, 2018, fecha de consulta 24 octubre 2023, en https://academic.oup.com/edited-volume/41302/chapter/352053036.

[77] G. I. Hernández, The International Court of Justice and the judicial function, cit., p. 1.

What is your opinion on the accusations that critics have made against De Las Casas, claiming he exaggerated reports of violence toward Native Americans?